Text written by:

Andrew Nahum

Andrew Nahum is Principal Curator of Technology and Engineering at the Science Museum, London and is a research tutor in the Department of Vehicle Design at the Royal College of Art. He has written extensively on the history of technology, aviation and transport for both scholarly and popular journals.

First published in 2009 by Conran Octopus Ltd a part of Octopus Publishing Group, Endeavour House, 189 Shaftesbury Avenue, London WC2H 8JY

www.octopusbooks.co.uk

An Hachette Livre UK Company

www.hachettelivre.co.uk.

This eBook first published in 2011 by Octopus Publishing Group Ltd.

Text copyright Conran Octopus Ltd 2009

Design and layout copyright Conran Octopus Ltd 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the Publisher.

Publisher:

Lorraine Dickey

Consultant Editor:

Deyan Sudjic

Managing Editor:

Sybella Marlow

Editor:

Robert Anderson

Art Director:

Jonathan Christie

Design:

Untitled

Picture Researcher:

Anne-Marie Hoines

Production Manager:

Katherine Hockley

Senior Production Controller:

Caroline Alberti

ISBN: 9781840915853

This eBook produced by Textech.

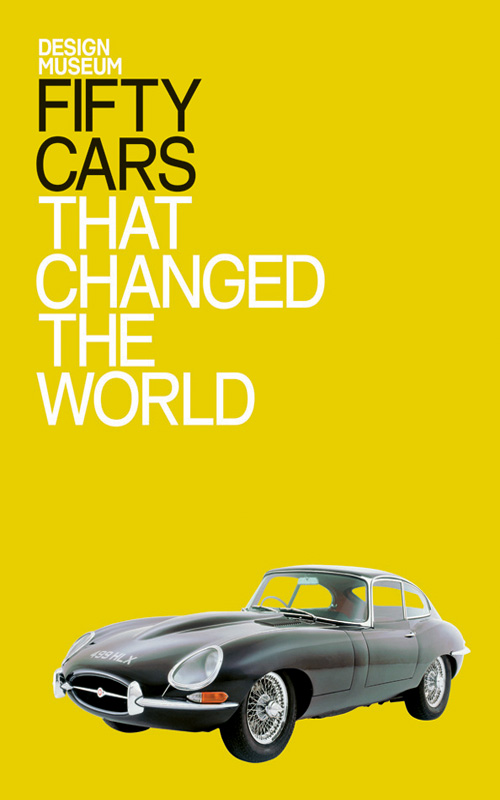

FIFTY

CARS

The car, as we know it, may well be facing oblivion in a world trying to convince itself that it is committed to reducing carbon-dioxide emissions, and rescuing its cities from the endless sprawl that comes from suburbs at densities that can survive only with car commuting. Yet for a century, the car has been a remarkably powerful catalyst for change, whose influence can be compared easily with that of the aeroplane or microchip.

From its earliest incarnations on, the car has demanded consideration and indeed attracted veneration on multiple levels: as sculptural object, as the product of avant-garde industrialism, and as a remarkable piece of engineering. Thus early cars borrowed their formal expression from their nearest relatives, the horse-drawn carriages; Ford famously modelled the first car production line on the techniques of the Chicago meatpackers; and the first steps towards self-propelled mechanical motion can be found in the eighteenth century. Equally, the car has been used as a measure of national prestige hence the successive attempts of Iran, Malaysia, Turkey, Brazil, India and China to establish themselves as global carmakers.

At the Design Museum we believe it is important to take these wider contexts into account, and not simply to focus on formal issues, no matter how seductive the stylistics can be. Our collection includes, for example, a wooden prototype of the car designed by Le Corbusier in 1928 and a Nissan S Cargo from 1987, one of the first examples of a car made by a mainstream carmaker that acknowledges the playful, emotional aspects of car design.

Deyan Sudjic, Director, Design Museum

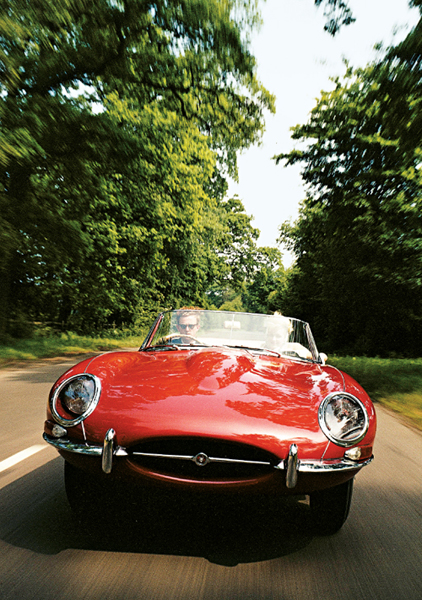

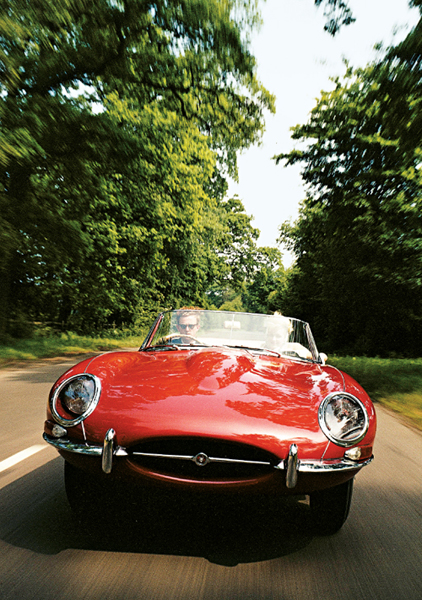

The Jaguar E-type a British icon in car design.

The Model T has two stories. The obvious one is that it was a sound, utilitarian device that motorized the United States. It was free from many of the quirks of other early cars, was thoughtfully engineered, and, for the time, was relatively easy to drive thanks to a semiautomatic epicyclic transmission.

Henry Ford (18631947) was an intuitive engineer who had trained as a machinist in Detroit and acquired a deep understanding of manufacturing techniques. But he never forgot his farmboy roots and wanted to produce a car of extreme practicality that would benefit the rural people to whom he felt closest. The flexible, well-sprung Model T was at home on the unmade rural roads that covered the United States at that time.

The Model T also has equally great significance as a symbol and advertisement for Fords production-line techniques and became the focus of the worldwide admiration for what has since become known as Fordism. It has been suggested that the moving production line is the perfect realization of the project started in the Enlightenment to turn men into machines. Thus the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher Adam Ferguson wrote, Mechanical arts succeed best under a total suppression of sentiment and reason. Manufactures prosper where the workshop may be considered as an engine, the parts of which are men. This could be a perfect description of Fords integrated Highland Park factory. Intriguingly, Ford and his methods impressed both Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin to an equal degree.

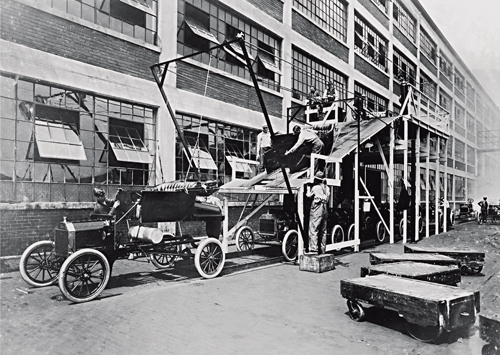

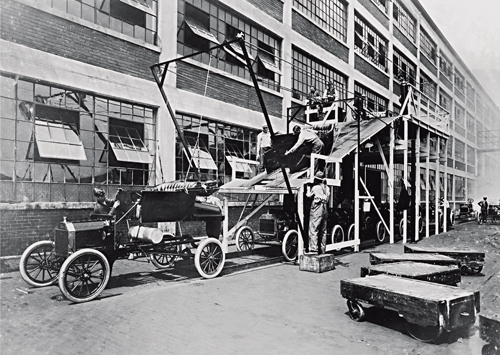

The concrete daylight factory at Highland Park, designed by Albert Kahn, was as much an innovation as the car for whose production it was designed. The body drop here, where the body meets the engine and chassis, became an iconic part of the car mass-production process. This outdoor section, photographed in 1913, must have been a temporary expedient, however.

The Ford Model T the car that motorized America.

Two car-mad young men have a dream to create their own brand. They put their design together in a parents garage, and hey presto! they have a popular product and an emerging motor business. So simple and today so impossible. But not in 1911 when Archibald Frazer-Nash (18891965) and Ronald Godfrey (18871968) had just left Finsbury Technical College, London, with diplomas in engineering and set up their own company, Godfrey & Nash (GN). Their car had a two-cylinder air-cooled motor, more like a motorcycle than a car, and accordingly came to be known as a cyclecar. By 1920 Archie had set up on his own, building more substantial Frazer Nash cars based on the same basic architecture.

One feature of the designs was that, instead of a gearbox, they used chains and sprockets of different sizes to give different speeds. These ran between an intermediate shaft under the drivers seat, to the back axle, and you changed gear by dog clutches that shifted the drive from one chain set to another. This was quick and effective. Moreover, the car had no differential gear, because the rear axle was a single piece, and drivers of GNs considered that the cars cornered best with plenty of throttle.

The GN and Frazer Nash cars epitomized British sporting cars in the period spindly and rakish, getting performance from lightness and simplicity. Super-sporting drivers turned them into improbably frantic hill-climb specials that often beat works entries from MG and Austin, such as Basil Davenports GN Spider, which was always suffused, in the race paddock, with the fragrant aroma of methylated spirits the fuel it ran on. GNs and Nashes also helped cultivate the generations of competitive owner-mechanics who became the backbone of that unique British institution, the Vintage Sports Car Club. An anonymous member even memorialized the inventors with this charming doggerel: