FIFTY BICYCLES

FIFTY BICYCLES

The bicycle is the most popular form of transport ever created. Because of its popularity and ubiquity, the bicycle is a machine we are all familiar with. As an archetype, the bicycle has been established since the creation of the safety bicycle in the late nineteenth century. Like other successful archetypes, such as the four-legged chair, money and the telephone, the basic form of the bicycle has remained largely unchanged.

In essence, bicycles are simple machines, designed to take energy generated by the bodys most powerful levers the legs and transfer it to the wheels. The mechanism that bicycles use to do this is a transparent one. The human eye can read this mechanism intuitively, appreciating how power is transferred from the legs to the wheels via the cranks and chain. Even the more complex elements such as the gears and brakes rely on simple mechanical solutions. In our increasingly digital world the bicycle remains unashamedly analogue.

Not all bicycles are the same, however. High-end performance bicycles are uniquely specialized, allowing athletes to excel at a particular discipline, while city run-arounds need to provide comfort, storage potential and longevity, and all within a particular price bracket. Essentially, the bicycle represents different things to different people, be it personal transportation, freight, a hobby, sport, exercise and very often a passion.

The Columbia safety bicycle, first produced by the Pope Manufacturing Company.

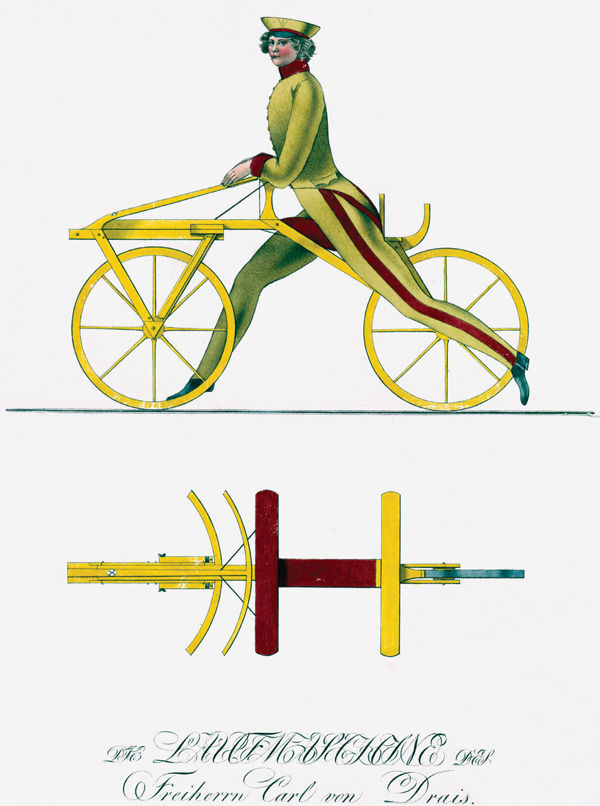

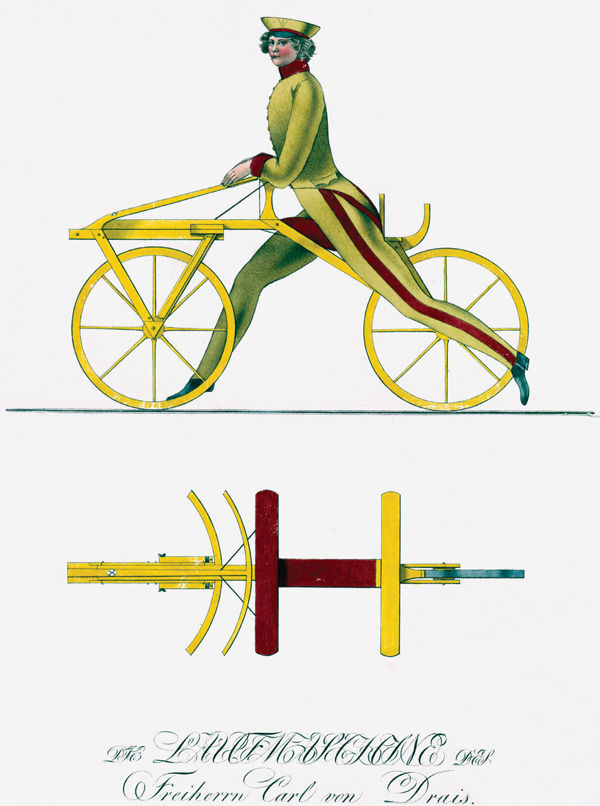

LAUFMASCHINE

c.1817

Baron Karl von Drais

While human-powered two-wheeled vehicles have been around in various guises for hundreds of years, it wasnt until the arrival of the Laufmaschine in 1817 that they first became a viable and relatively widely used form of transport. The Laufmaschine which literally translates as running machine was conceived by the German civil servant Baron Karl von Drais (17851851) as an alternative method of transportation to the horse so that he could navigate the narrow tracks of the forestry estate where he worked.

Following on from previous two-wheeled vehicles, the Laufmaschine used in-line wheels and was constructed predominantly from wood. However, the addition of a rudimentary steering mechanism set the Laufmaschine apart from previous designs. As well as providing the rider with the obvious benefit of directional control, steering also had a dramatic effect on balance. The ability to make small adjustments to the front wheel enabled the rider to rebalance their weight and stay seated on the Laufmaschine without the need to touch the floor. This remarkably automatic reaction is something that we all acquire, through instinct as much as anything else, when we first learn how to ride a bike.

The Laufmaschine proved extremely popular and similar designs, known by various names including dandy horses and hobbyhorses, were soon being manufactured by enthusiasts and coach builders all over the world.

Karl von Drais saw the Laufmaschine as having potential to be sold across Europe. These Illustrations are taken from a prospectus von Drais sent to the Prince of Frstenberg in 1817 in an attempt to raise financial backing for the machine.

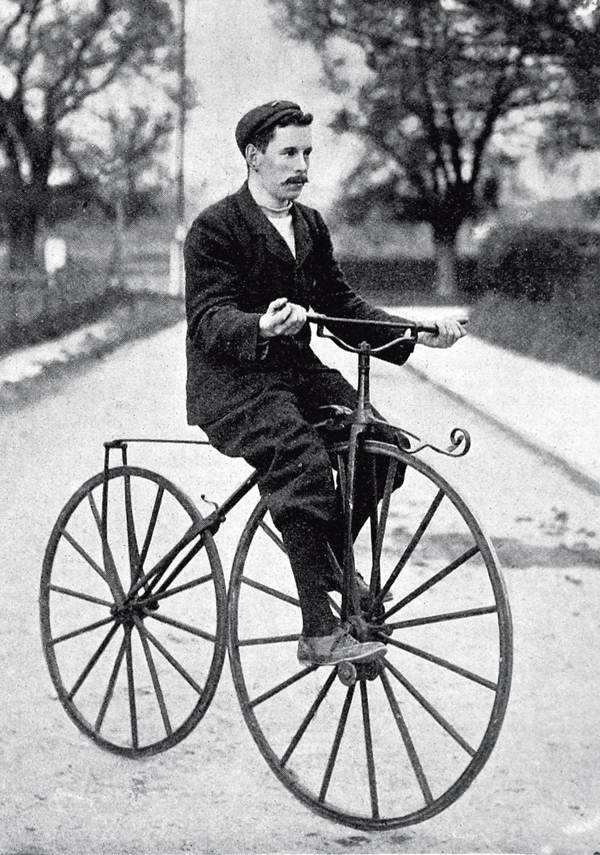

VELOCIPEDE

c.1863

Pierre Michaux / Pierre Lallement

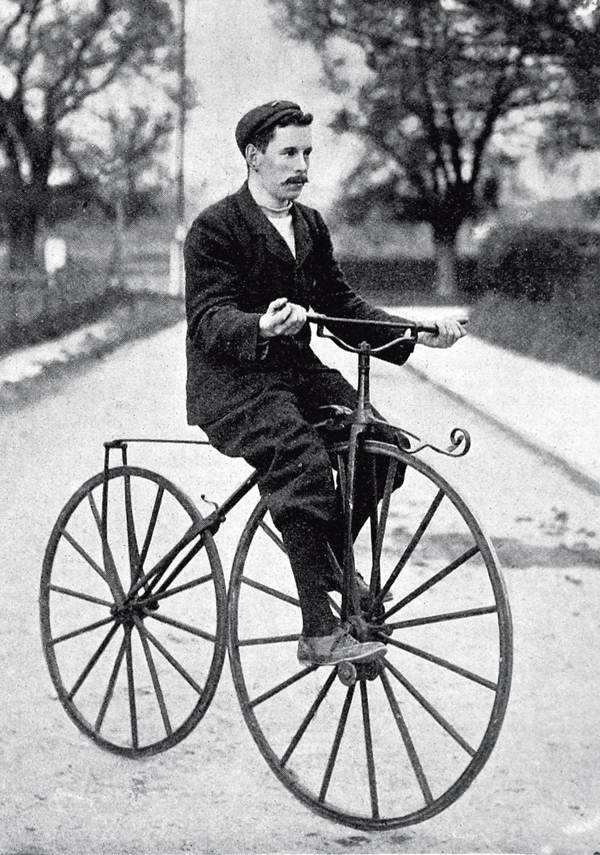

The next major step in the evolution of the bicycle came with the introduction of mechanical propulsion. Prior to this, bicycles were usually pushed along by the riders feet using a motion similar to running. There is some dispute as to who was responsible for first introducing pedals, with two different Parisian metalworkers both having valid claims on the invention. Around 1863 both Pierre Michaux (181383) and Pierre Lallement (184391) began manufacturing designs with rotary cranks and foot pedals attached to the front wheel hub.

Other experiments in mechanical propulsion included foot-operated treadles, which were similar to the foot panels used to drive looms and sewing machines. However, these solutions were never particularly practical and it wasnt until the late 1860s that bicycles using pedals similar to ones we recognize today were in widespread use. These came to be known as velocipedes from the Latin for fast foot.

While these designs did allow far greater speeds to be achieved, they were not without their problems. Pedals attached to the front hub made it very difficult to steer and pedal simultaneously and the poor ride quality gave rise to the nickname bone shaker. As the velocipedes improved, and cyclists became more aware of their capabilities, cycling clubs started to form and the first organized races were held.

A typical image of a cyclist on a velocipede or bone shaker bicycle, widely used throughout the 1840s and 1850s. This type of bicycle earned its moniker through the use of solid wood or metal wheels.

HIGH WHEELER / PENNY-FARTHING

c.1870

The penny-farthing, or high wheeler as it was more commonly known, evolved from the velocipede as engineers and manufacturers realized that the larger the wheel the farther one would travel with a single rotation of the pedals. These designs coincided with advances in metalworking that enabled stronger, lighter and more complex frames to be constructed.

As the popularity of high wheelers increased, manufacturers started to deliver an ever-increasing range of models. Each new model provided small improvements in areas such as handling, spoke and wheel tension, and advances in drivetrain mechanics. Riders could also choose a machine that best corresponded to the length of their leg.

Regardless of these advances, some fundamental problems remained. Mounting and dismounting a high wheeler was notoriously difficult as the saddle could be well over a metre (3ft 3in) high and the vehicle needed to be in motion before the rider could take a seat. They were also incredibly dangerous machines that needed skill and, more importantly, courage to ride. It was the frequent incidents and crashes involving high wheelers that gave rise to the phrase taking a header.

A postman delivers mail using a penny-farthing. The speed and efficiency that the bicycle may have introduced to the postal service was undoubtedly countered by the number of accidents!

SAFETY BICYCLE

c.1880

Henry J Lawson

The earliest example of a rear wheel chain-driven bicycle is a drawing that appears in Leonardo da Vincis Codex Atlanticus of c.1493. A design by the British inventor Henry J Lawson (18521925) of 1879 was in all probability the first chain-driven bicycle of real significance. Chain drives enabled a large sprocket attached to the pedal cranks to be connected to a small sprocket attached to the rear wheel. This simple mechanism multiplied the ratio of pedal revolutions to wheel revolutions, thus eliminating the need for the large wheels featured on high wheelers and precipitating a return to bicycles with smaller, similarly sized wheels.

Next page