For Angelene

I want to extend special thanks to Jos Antonio Castillo Garcia, Dan Watman, and Ben McCue, without whose collaboration andgenerosity of spirit this book would not have been possible.

A Note to Readers:

Names have been changed and identities have been obscured inorder to protect migrants and the smugglers who cross them.

The bicycle will be found, said the Sergeant, when I retrieve and restore it to its own owner in due law and possessively. Would you desire to be of assistance in the search?

FLANN OBRIEN, The Third Policeman

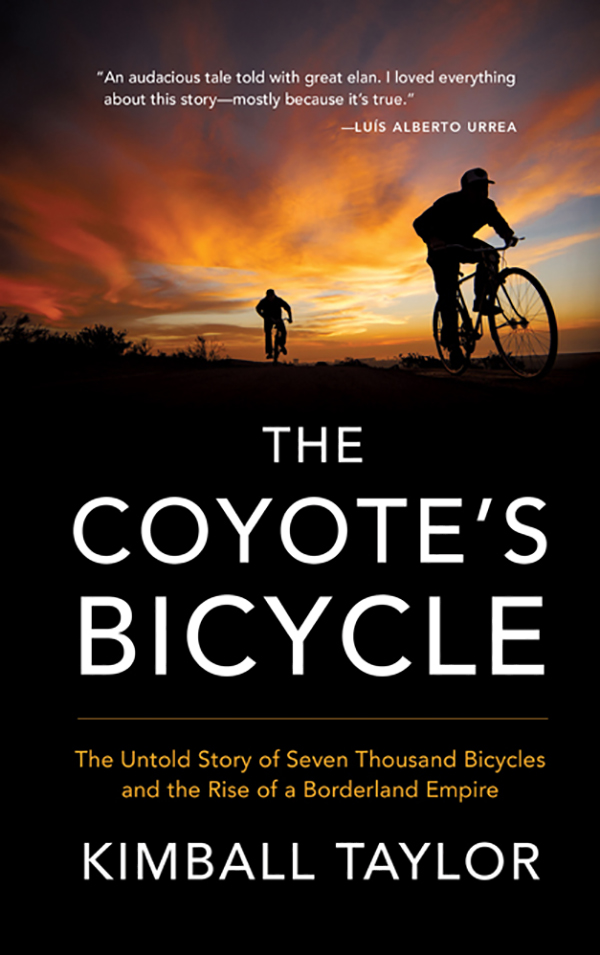

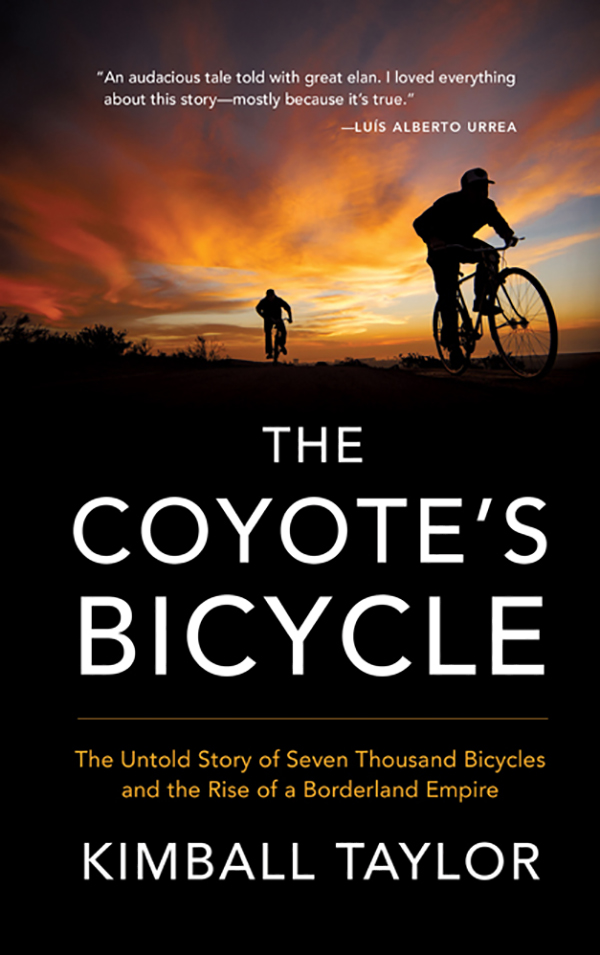

PHOTO JP VAN SWAE

KIMBALL TAYLOR is a long-time contributor to Surfer Magazine and the author of two books about the sport: Return by Water: Surf Stories and Adventures and Drive Fast and Take Chances. Taylor holds a BA in journalism and an MFA in creative writing and is an alumnus of the Squaw Valley Community of Writers.

A Note on Sources and Acknowledgments

While researching the development of the bicycle, my reading stumbled upon historical accounts that, for me, have become like favored items I keep in a kind of mental Wunderkammera cabinet of curiosities. Often, in the process of writing this book, Id return to these images, dust them off and spin them around. One is set at the Paris Exposition Universelle in the summer of 1867. Inside beautiful fair buildings, artists, explorers, and scientists had assembled a collection meant to represent the forefront of human knowledge. So much effort had gone into selecting these astonishing displays that, it seems, the entire endeavor overshot a development that had occurred practically in the shadows of its scaffolding: the humble bicycle.

French inventors had just recently given the bicycle pedals, an event that held implications for all forward movement. Yet the bicycle was not admitted among the achievements of the exposition. The slight did not matter: regular Parisians rode their new bikes to the fairgrounds anyway, and, at the exposition steps in the Champ de Mars, they pedaled their wheels in lazy, entertaining, joyous circles.

Twenty-six years later, the main attraction at Chicagos Worlds Columbian Exposition was none other than George Ferris monstrous wheel, a contraption that looped thirty-six passenger cars 264 feet into the sky. It was an iconic engineering achievement intended to rival the Eiffel Tower, as well as, essentially, just a giant bicycle wheel: axel, spokes, rims and all.

Another scene I return to occurred indoors on wooden, elliptical rinks. As the bicycle craze of the late 1800s hit America, manufactures realized that a major impediment to sales was the fact that potential customers didnt know how to ride. The go-around was to establish cycling schools. When I discovered, through El Negros interviews, that the bicycle coyote organized such lessons for migrants who had not yet learned to balance on two wheels, the distance between the very first beginners and those on the border with El Indios gang collapsed for meI saw only gyrations through time.

I suppose what my visual curios have in common is a type of circular synchronicity, pictures and stories that always come back around to their beginnings. Outwardly, the developments of the USMexico border and the bicycle dont have much in common. But they do share this circular nature, this piquant for irony. Some of the stories that occurred on the border were just too thick with it to include. For example, a common legend has it that construction on the earliest government fence was contracted out to American ranchers. Upon completion, the very next act of those locals was to cut holes in the fence to give themselves access to Tijuanas delights. Or, in more recent times, the government contracted with a firm to extend a physical boundary into San Diegos interior. This fence company was later charged with having used illegal labor in the building of the fortification designed to keep such labor out.

The search for El Indio took on a similar character, always cycling back to the few bits we could be certain about, variously plying the story with deeper mysteries. For El Negro, the characters involved in the bicycle operation appeared and disappeared again, as is the nature in a city where modern communication can be an expensive luxury. The odd numbered chapters that explore the rise of El Indio are very much the result of having learned the coyotes story over time, from the memories of disparate individuals. El Negro conducted dozens of interviews with the gang, beat cops, and other officials, often returning for critical details. Illustrations of the same events, depending on the teller, differed in shape and scope. El Negro and I probed the veracity of these tales by visiting the scenes of the eventsPanten Jardn, where Marta is buried, or El Gato Bronco, or Los Laureles. Separately, I traveled to Oaxaca, Mexico, to small villages like the one where El Indio was born, to learn something not only of the place, but of the era in which Pablito and Solo resided there.

To understand the experience of migration I spoke to people who lived in the Tijuana River, deportees I met in Playas, people who had returned from the US to Oaxaca, people who had once crossed illegally but had obtained citizenship, and also to Dreamers, the children of crossers. The federal case against the brothers Raul and Fidel Villareal, the Border Patrol agents who were convicted of crossing migrants in Border Patrol vehicles, was especially enlightening. Enforcement agents Id met, speaking on condition of anonymity, were extremely generous with their time and experiences. Victor Clark Alfaro, a human rights activist and lecturer at San Diego State University, invites human smugglers and street prostitutes to his office in Tijuana, where the subjects explain their work for his SDSU students via a video feed. I was able to attend one of these events at his office, and found Clarks use of primary sources in this field unparalleled. What I learned in person was aided by the books and articles of Peter Andreas, Lawrence A. Herzog, and Joseph Nevins.

So many people contributed to The Coyotes Bicycle in small ways, I could never thank them all. Early readers Chris Patterson, Brian Taylor, Cameron Taylor, Angie Fitzpatrick-Taylor, Zach Plopper, and Tim Barger helped to foster the work along. Grant Ellis labored over rugged terrain to capture the cover image. Shawn Bathe acted as both my Baja co-pilot and artistic collaborator. Almost all of the principals and interview subjects in this story were unstinting with their information. Id like to thank: Dick Tynan, Terry Tynan, Carol Kimzey, Sharon Kimzey-Moore, Jesse Gomez, David Gomez, Greg Abbott, Chris Peregrin, Mike McCoy, Serge Dedina, Oscar Romo, Janine Ziga, Eric Kiser, Kim Zirpolo, Tarek Albaba, Johnny Hoffman, Brian Anderson, Ron Nua, Eric Amavisca, Aaron Garrison, Maria Teresa Fernandez, Ana Teresa Fernandez, Eric Blehm, William Finnegan, J. Jesus Cueva Pelayo, Vianett Medina, Amy Isackson, Gabe Duran, Steve Hawk, Ian Taylor, Ken Gomez and the volunteers of Bikes del Pueblo, the Binational Conference on Border Issues, Squaw Valley Community of Writers, Tony Perez, Nanci McCloskey, and the staff of Tin House Books.

And in hopes that what El Negro promised his sourcesNo one will know who it is except the one who knows his own lifeis indeed the case, Id like to thank El Indio, Solo, Roberto, et al.

Next page