INTRODUCTION: THE END OF RATIONING

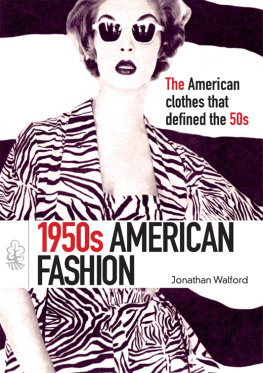

I n May 1949 clothing rationing ceased in Britain, almost exactly four years after the Second World War officially ended in Europe. Rationing was intended to offer equal shopping opportunity, ensuring that everyone, rich and poor alike, having the same clothing rations, could purchase up to forty-eight (reduced from sixty) coupons worth of garments per year. In practice, ration books were widely abused, stolen and forged, meaning that the scheme failed to live up to the ideals that inspired its conception. For her January 1949 wedding, a young bride-to-be, Rachel Ginsburg, bought a chic red wool suit from a Liverpool department store using coupons donated (illegally) by her classmates. The jackets nipped waist and flared peplum made it one of the first New Look garments Rachel had seen, a term coined by the American fashion journalist Carmel Snow. On seeing Christian Diors 1947 debut collection, featuring rounded shoulders, tiny waists and long skirts, either lavishly full or reed-slim, she proclaimed it showed such a new look. Although other Paris couturiers had introduced fuller skirts and wasp waists between 1944 and 1946, Dior became the designer linked with the curvaceous silhouette that swept away the boxy shoulders and skimpy skirts of the war years. Instantly desirable to devoted followers of fashion worldwide, a whole decade later, tiny waists and full skirts were still recognisably part of the late 1950s fashion vocabulary.

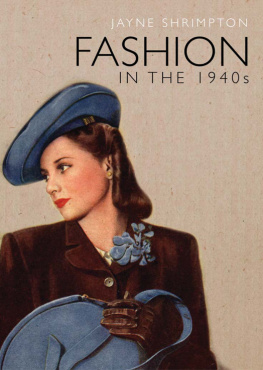

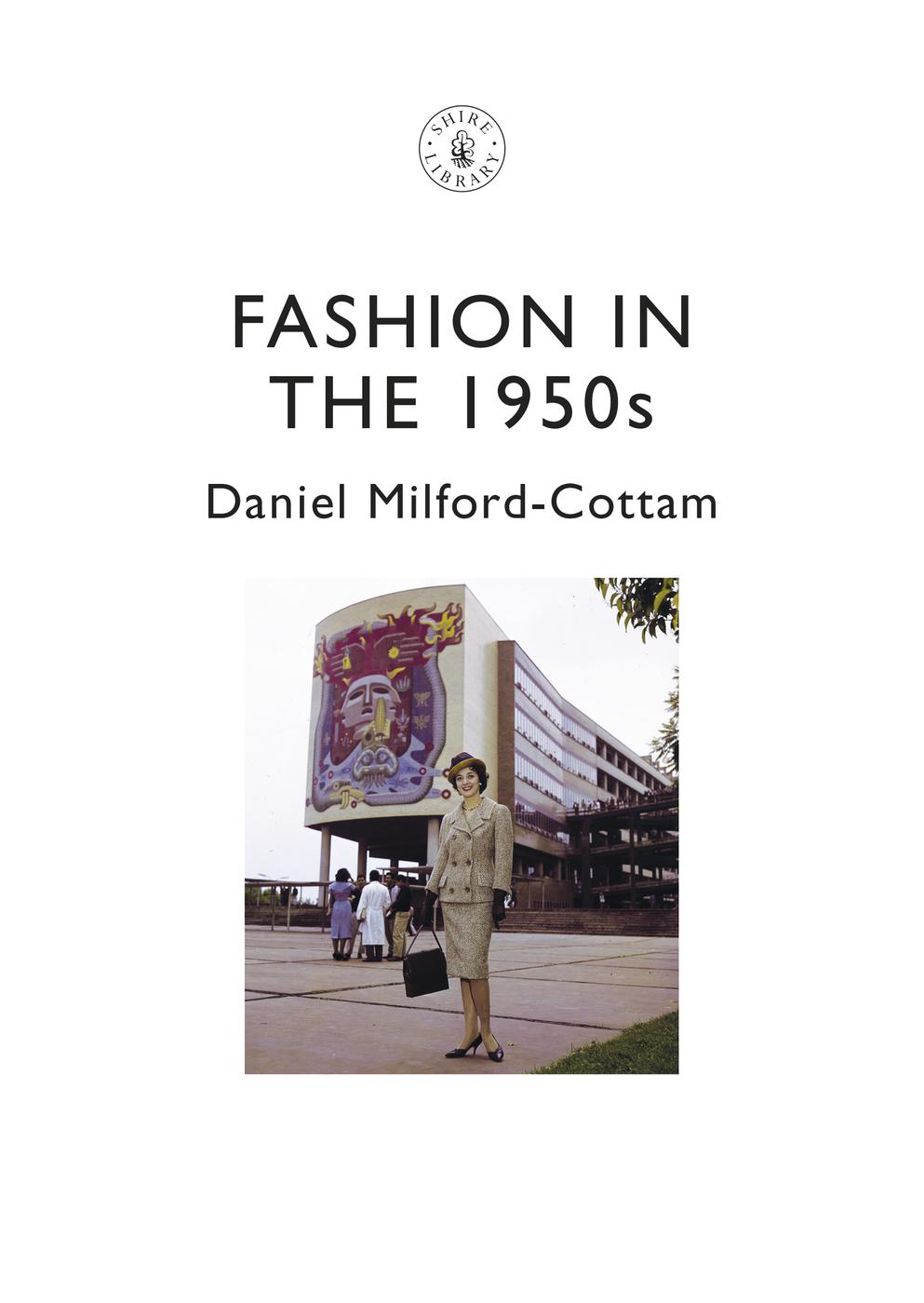

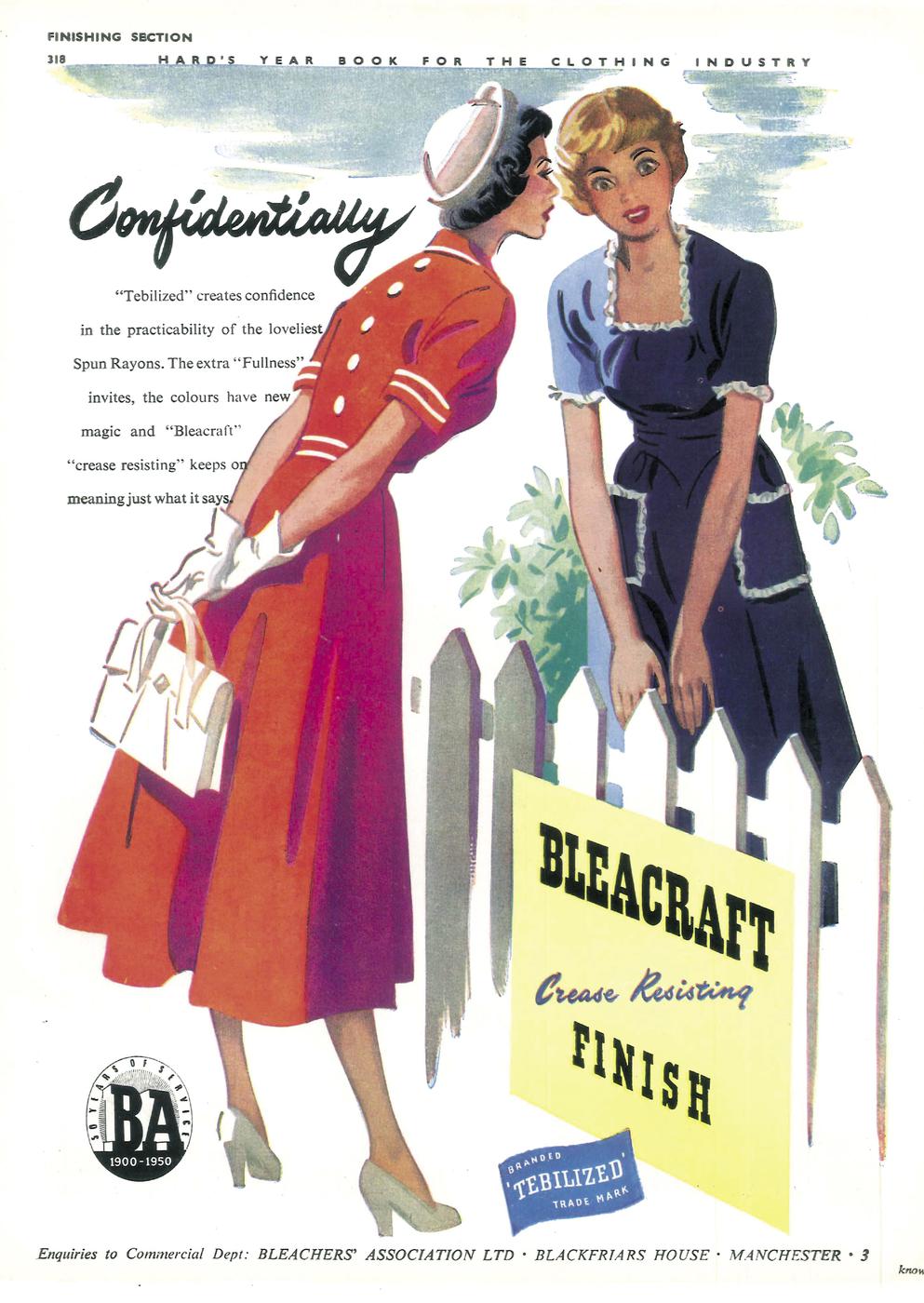

By 1950 the New Look influence was firmly established in longer, mid-calf-length skirts and rounded shoulder-lines. The beautifully matched gloves, small hat, handbag and shoes epitomise early 1950s elegance. This advertisement from a 1950 trade journal promotes a new crease-resistant fabric finish.

The British response was mixed. While politicians rushed to decry the New Look as unpatriotic due to its abundant use of scarce fabrics, and King George VI forbade his daughters to wear it, many British women responded with longing. Barely a year later, even Utility dresses showed its influence, with softly rounded shoulders and skirts cleverly cut to suggest fullness. The Government-led Utility schemes, manufacturing furniture and housewares as well as clothing, were designed to offer economically made but excellent quality merchandise. Despite this, ready-to-wear clothing was seen as an extravagance, with many people wearing what they could make or afford. As a result of austerity and shortages during the 1940s, second-hand clothing became increasingly acceptable. With alterations and cleaning, garments snapped up at jumble sales and charity shops gained a new lease of life for the thrifty dresser, but were unattractive to those demanding absolute newness and freshness in the post-austerity years.

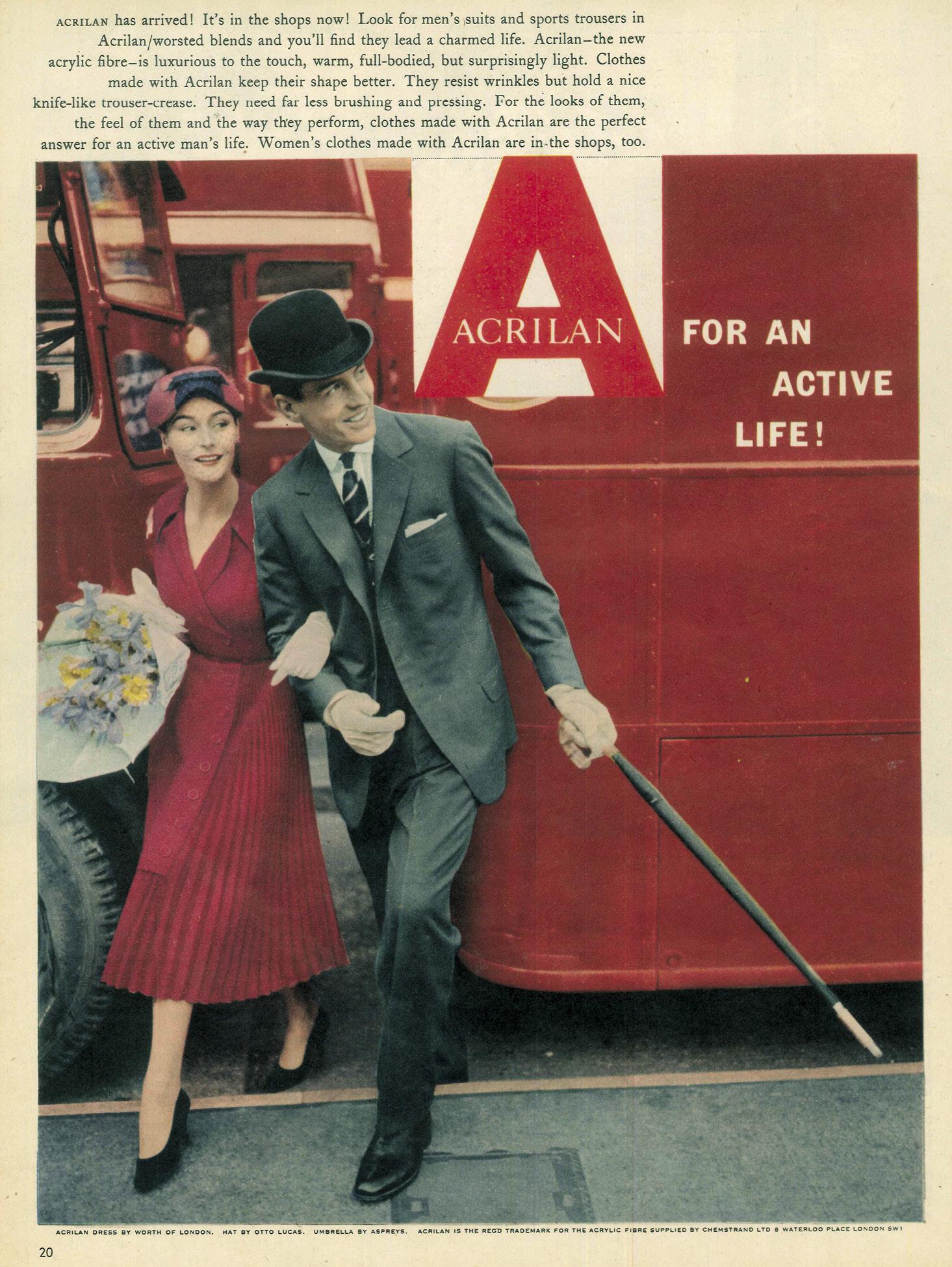

The media encouraged consumer demand for the most modern and technologically innovative textiles, fashions and housewares. Manufacturers vied with each other to offer the newest, most exciting synthetic fabrics. By the end of the 1950s, synthetic and synthetic-blend materials were widely available in every form, from gossamer chiffon to heavy tweed, sold under countless brand names. Cardigans might be made from acrylic-based synthetics such as Orlon, while a late 1950s evening gown might be made from acetate satin brocaded with metallic Lurex, interlined with non-woven polyester Pellon and nylon net petticoats, and accessorised with a nylon faux-fur stole.

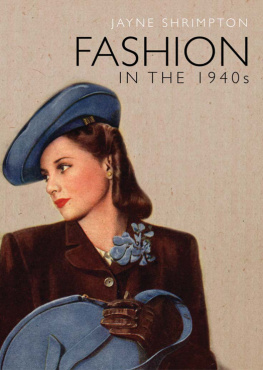

Paisley-print cotton dress by Nettie Vogues Ltd, Britain, 1948. The Double Elevens label, introduced in 1946, indicated non-Utility garments from a manufacturers most expensive range. Despite this, the fabric is used carefully, with clever pleats and horizontal bands of ribbon suggesting New Look fullness. The fichu collar gives a softly rounded shoulder line.

In addition to this, fabric designers produced a vast range of original patterns for womens and childrens clothes and even for mens holiday shirts. While the 1950s is epitomised by overblown floral designs such as those produced by Horrockses, even that brand offered dresses printed with lobsters or eggcups, and was far from unique in offering fabrics designed by leading artists such as Eduardo Paolozzi. Many of the most famous modern artists of the day, including Picasso, Dal, and Marc Chagall, produced distinctive painterly designs for fabrics. Even science became involved, offering up newly discovered cell-structures as inspiration for a wave of atomic designs that not only spread across cloth, but onto furniture, wallpaper and even ceramics. There seemed no limit to the imagery to be found in textiles.

Many women made their own clothes, a necessary skill during the war and immediate post-war years. Knitting, crochet and sewing patterns were widely available. While it was possible to buy knitted garments directly, such as the haute knitwear created by Maria Luck-Szantos team of knitters, and ready-to-wear clothing was increasingly available, many women preferred to run up simple frocks and knitwear at home. This helped save money for necessary ready-made purchases such as shoes, coats and most mens clothes. The skilled dressmaker on a limited budget could produce quite sophisticated garments for herself and her friends, although for those with less time (or aptitude) for dressmaking, ready-to-wear was available at many price levels and could be bought from department stores or local speciality shops. While mail-order shopping was not new, the 1950s saw a sharp increase in the number of catalogues on offer, many laden with pictures of enticingly presented garments at prices aimed towards the retailers target audience. Many high-end dresses, or at least, their accessories, were likely to be purchased from boutiques a relatively new innovation in fashion retail.

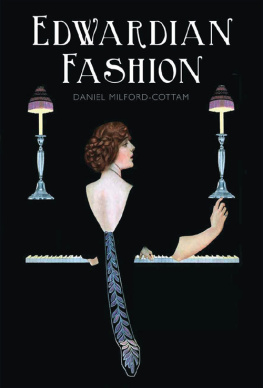

Both the womans dress (by Worth of London) and the mans suit in this 1952 advertisement are made using Acrilan a trade name for acrylic. Synthetic fabrics were widely advertised, and association with couture names such as Worth helped make them acceptable.

The boutique concept originated between the wars, with couturiers such as Elsa Schiaparelli creating striking retail spaces linked to their salons for the direct sale of perfumes and luxurious hats, gloves, shoes, costume jewellery, lingerie, dress ornaments and simple ready-to-wear. Even after Schiaparellis couture house closed in 1954, licensing agreements meant that Schiaparelli fragrances and merchandise including furs, hats, accessories, lingerie and some garments remained widely available through independent boutiques and department stores. Even the slightly less well-off customer might be tempted to purchase an exquisite silk rose with diamant dewdrops from Hardy Amies, or a pair of Dior stockings.

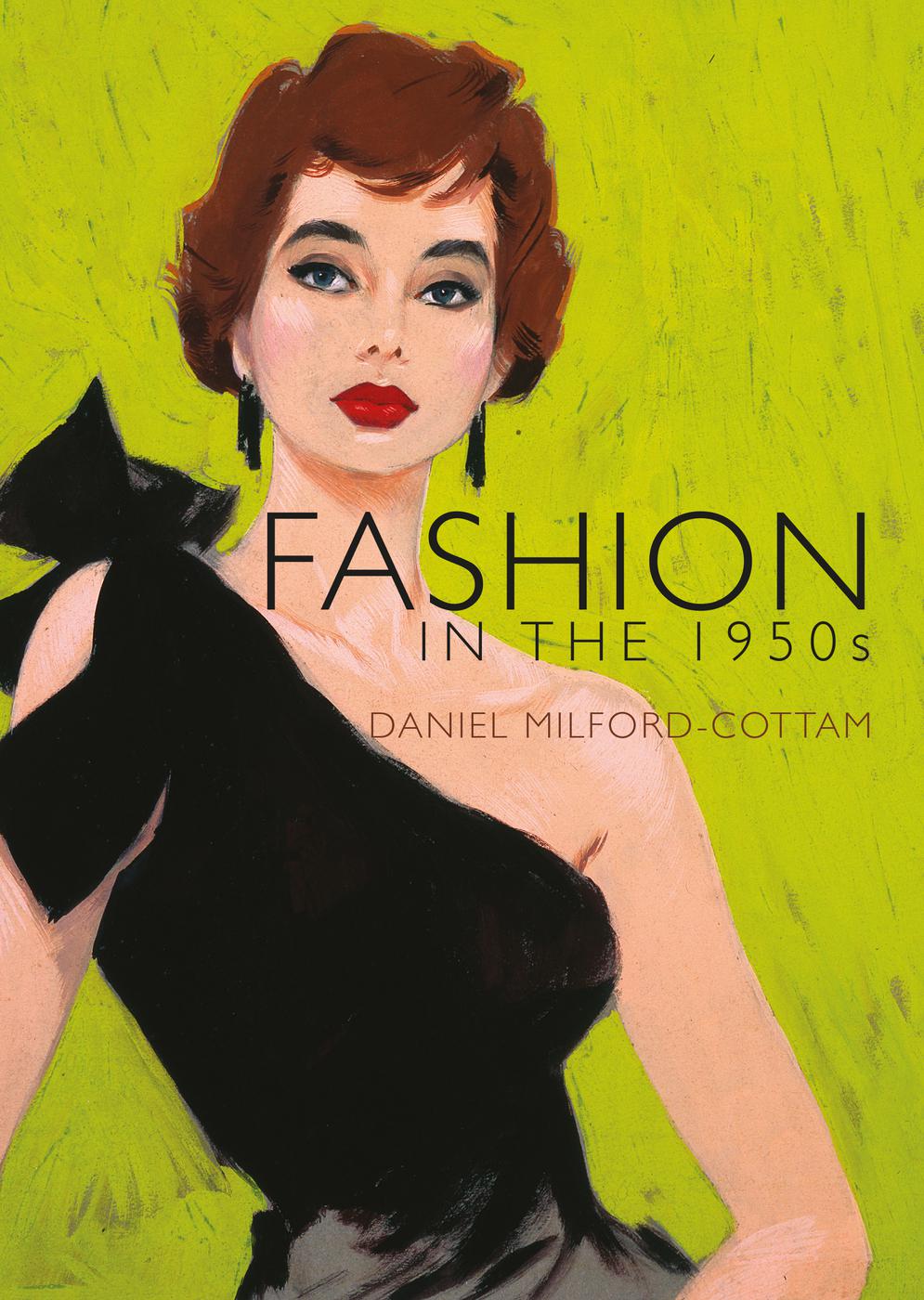

This 1953 cocktail dress by Horrockses uses an exclusive yellow, black and white printed cotton designed by the Scottish-Italian artist Eduardo Paolozzi.