Contents

Guide

Contents

What You Can Learn

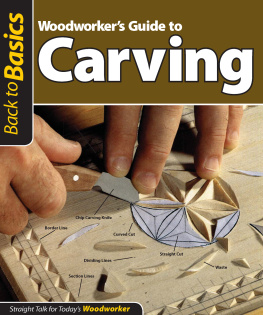

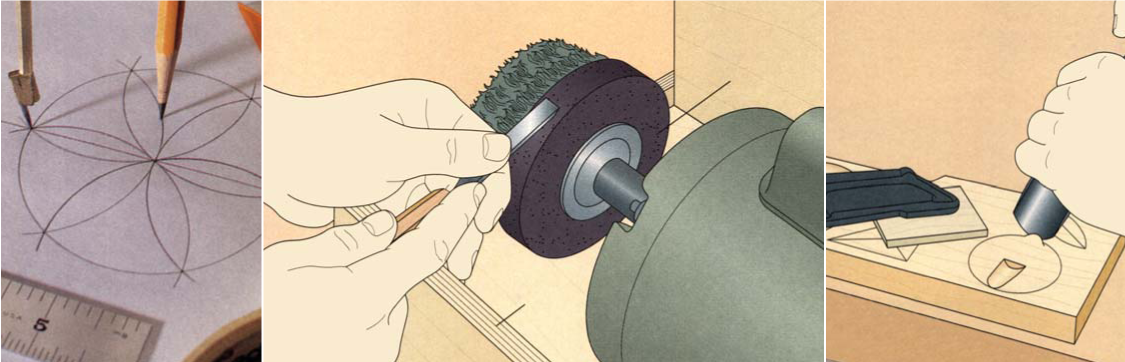

Despite the enormous variety of tools at a woodworkers disposal, most carvers perform their work with a dozen or so tools.

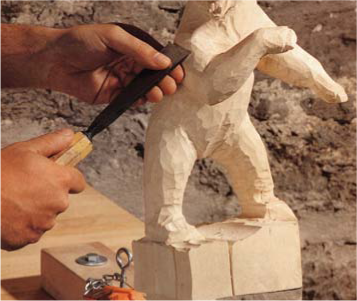

Nothing takes the place of practice, but you can master the basics of carving with a few deft movements of a chisel.

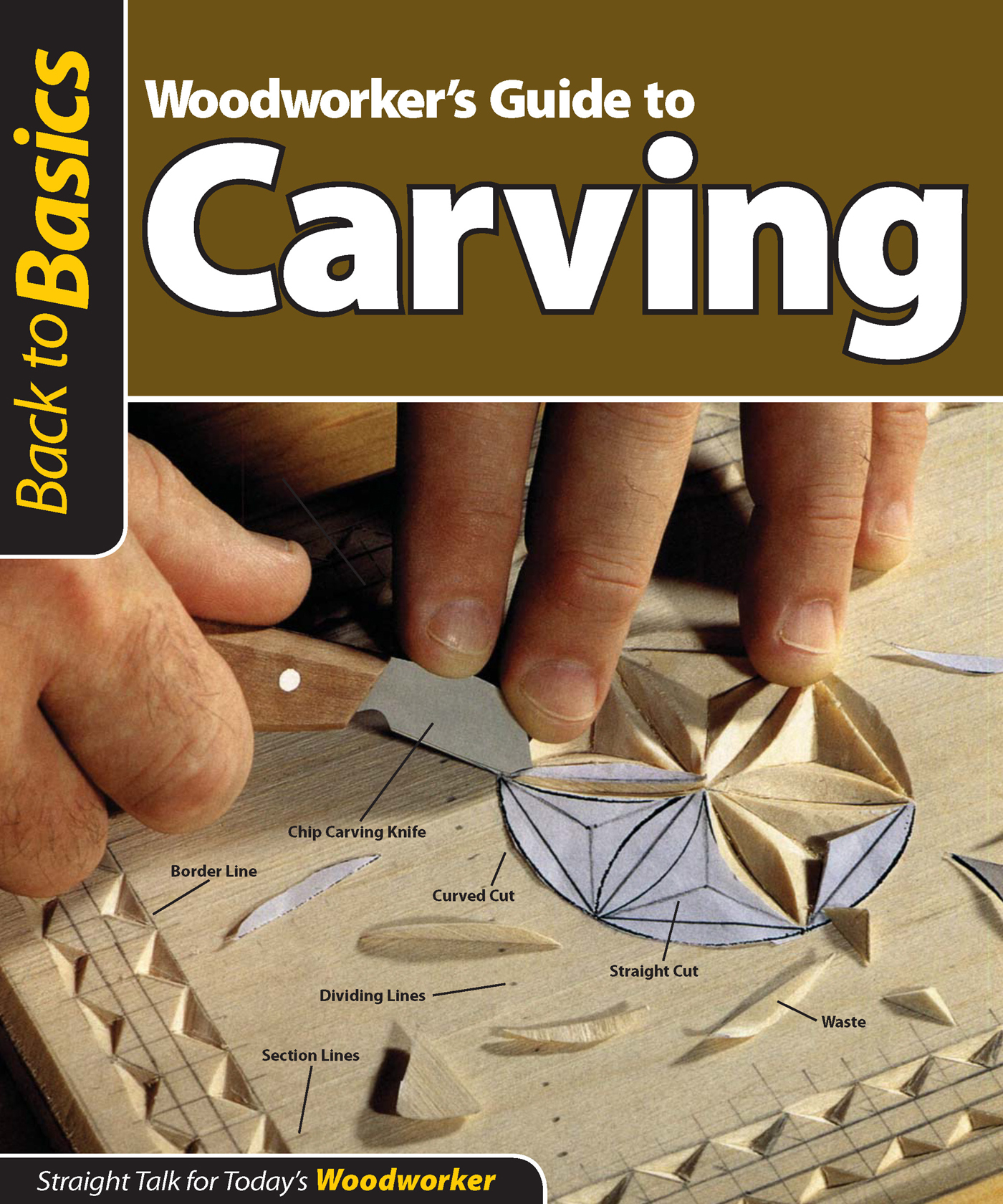

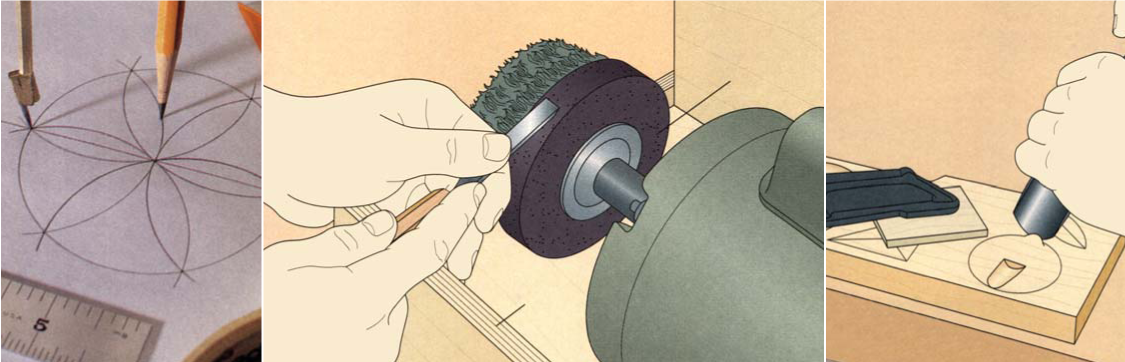

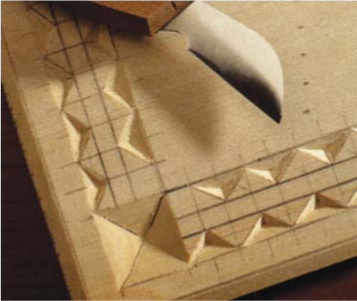

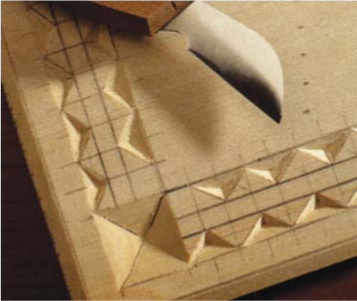

To the uninitiated, chip carving may seem complex but it is actually a fairly straightforward process, with room for infinite variation.

The techniques of relief carving can be applied to a variety of subjects from bowls to scenery.

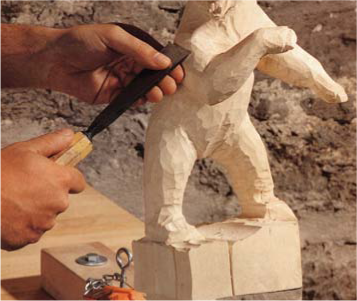

Whether the piece is a bust, a wildlife carving, or a design element on a claw-and-ball foot, you should undertake a careful study of the project before beginning.

Chip Carving

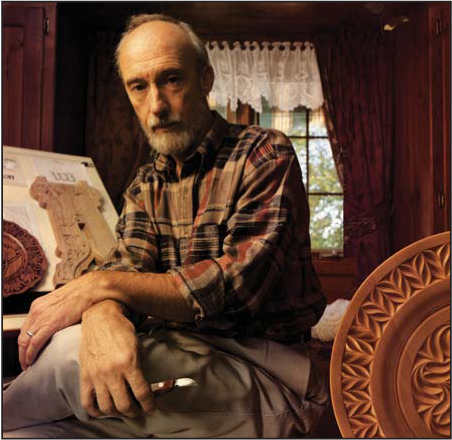

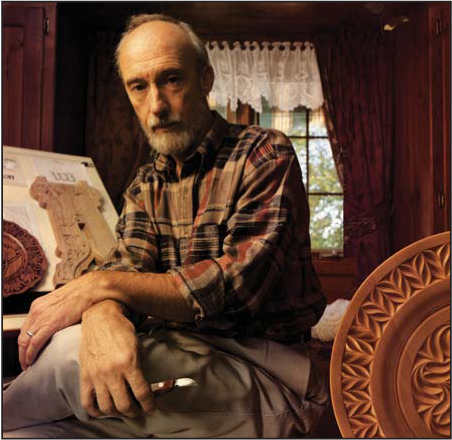

As a small child I was fascinated with every aspect of wood: its feel, its smell, and the ever-changing beauty of its grain. From as far back as I can recall, my father supplemented the family income by pursuing his passion of furniture refinishing and antique restoration. And, from the age of five, under the watchful eye of my Norwegian grandfather who lived with us, I was tutored in carving wood. Thus began a wandering journey that would bring a lifetime of joy, excitement, challenges, and friendships.

Working with wood, from topping trees to boatbuilding, was an activity I continued into adulthood and the one that gave me my greatest pleasure. So when the opportunity to study in the woodcarving center of Brienz, Switzerland, presented itself, I thought the world had stopped to let me on. This was the chance of a lifetime.

The experience of carving in the midst of masters whose skills were rooted in centuries of knowledge and tradition proved exhilarating. Learning carving from these craftsmen included acquiring discipline and an appreciation of art and architecture, particularly Gothic styles, upon which much of chip carving is based. I had the added good fortune of studying close to ancient castles and cathedrals, where I could observe firsthand design concepts and theory put into practice.

I was easily drawn to a Swiss method of chip carving primarily because it seemed to represent the essence of simplicity. Though this style was relatively unknown in North America at that time, I realized that with only two knives and a basic understanding of technique anyone could, in a relatively short period of time, produce amazingly satisfactory work.

Perhaps my enthusiasm for chip carving has been the spark that ignited similar fires in so many others Ive had the pleasure of teaching throughout the years. If it is true that we teach that which we love to learn the most, then carving, particularly chip carving, has been the most perfect vocation for me.

- Wayne Barton

Wayne Barton is the founder of The Alpine School of Woodcarving, and author of several books on chip carving published by Sterling Press, including New And Traditional Styles of Chip Carving. He lives in Park Ridge, Illinois.

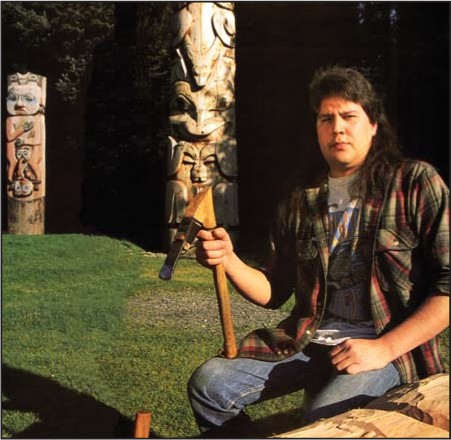

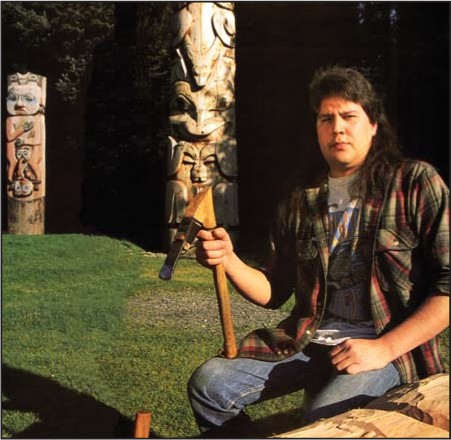

Traditional Tlingit Carving

My mother was often upset at my fascination with knives. Like many young boys, I was constantly reminded of the danger of playing with them. But to me, the serrated steak knife that I snuck out of the drawer as an eight-year old was simply a tool to be used for carving wooden blocks into Tlingit Northwest Coast forms.

My earliest exposure to wood carving was a demonstration given in elementary school. My first project was a simple wooden halibut hook. That hook started me on a search through museums and bookstores, collecting information on traditional Northwest Coast art forms. That same year, I began making bentwood boxes in the traditional manner of my people: Cedar planks are left to steam all day in an open pit over a fire buried with layers of spruce branches, skunk cabbage leaves, and seaweed. The cedar planks are then pliable and can be bent to form a four-sided box with only one seam.

Wood carving classes were not simple to find in most small Alaskan communities 23 years ago, so for the most part I practiced the skills on my own. In the early 1980s, I was fortunate to be hired by the Ketchikan Totem Heritage Center as a tour guide and demonstrator. The opportunity at the Center to study and practice carving, and to learn the Tlingit culture, gave me insight into the art form, its meaning, and message.

In the case of the 20-foot totem pole in the picture, I first drew the plans of the totem on paper and then carved a small wooden model. The figures on the model were then measured and sketched to scale onto the pole, working from the bottom up. Each figure was roughed out and finished before moving to the next highest one, using many different kinds of adzes, such as straight adzes, gutter adzes, and lipped adzes. I painted each figure as I move up the pole.

The steps taken to learn my craft have been many, starting with years of practice devoted to the study of design, drawing, painting, and most importantly, the capability to shape these designs into a piece of raw cedar. The finished product, whether it be a totem pole, a bentwood box, a ceremonial mask, or a bowl must convey the past, present, and future of the Tlingit people.

- Tommy Joseph

A member of the Tlingit tribe, Tommy Joseph is a carving instructor at the Southeast Alaska Indian Cultural Center in Sitka, Alaska.

A Charles II Bellows

From the time man discovered that he could fashion something from wood other than a spear or a truncheon, he has been hard at work carving, both as a trade and an avocation. Today, wood carving is in a state of flux. Even the keen amateur working in his hobby shop appears to be moving away from the use of gouges and sweeps toward small hand-held motor tools that seem to disintegrate wood very efficiently in any grain direction. On the workbench and shop floor, wood chips and shavings are being replaced with very fine sawdust.