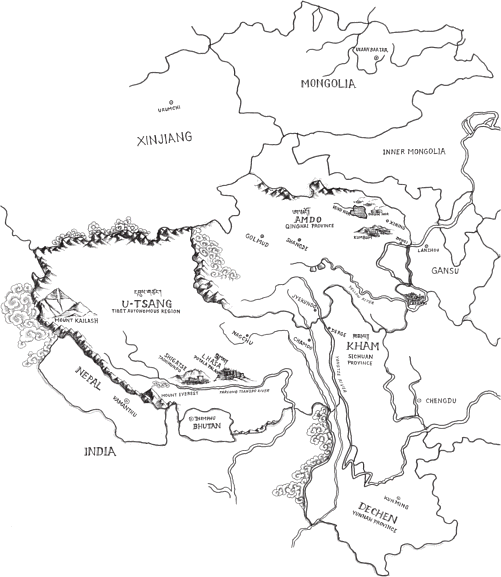

In 1998, I learned that Arjia Rinpoche, abbot of the renowned Kumbum monastery in Tibet, had come to the United States from Guatemala as a political exile. At the time, I was in New York to give a talk. It had been almost 40 years since I, too, had left Tibet, seeking freedom in exile, but even longer since I was last in Kumbum, where my own monastic life began. Now, here in front of me, was the abbot of my monastery.

Kumbum is the birthplace of Je Tsong Khapa, the founder of the Gelug tradition of Tibetan Buddhism to which I belong. For the first 200 years of its existence, Kumbum was a small pilgrimage site; then, in the sixteenth century, the Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso, transformed it into a great monastic university.

The monastery was located not far from where I was born, and I spent some time there in the mid-1950s, when Arjia Rinpoche was still a child. I have happy memories of Kumbum as it used to be, its beautiful, majestic buildings nestled into green hills. But recalling, too, what had happened to so many monasteries at the hands of the Communist Chinese, and what the Kumbum monks must have suffered, I was eager to hear what Arjia Rinpoche had to say about the monastery and how Tibetans in the vicinity were faring.

Rinpoche and I had a very warm meeting. So much had happened to both of us, and the way our lives have unfolded has been so different; but we both continue to share a concern for the welfare of the people of Tibet. Given his experience of working with the Chinese authorities, as well as his having met the president of China, Jiang Zemin, I hoped he might be able help us improve our dialogue with the Chinese. With that in mind, I asked him to write to President Jiang Zemin.

In due course, Arjia Rinpoche established the Tibetan Center for Compassion and Wisdom in Mill Valley, California, which did very well. Later, when my elder brother Tagtser Rinpoche fell ill and could no longer manage the Tibetan Cultural Center he had set up in Bloomington, Indiana, I thought of Arjia Rinpoche. He had the experience to take it on, and I felt he could restore and manage this important center.

As always, Arjia Rinpoche accepted the challenge. Another connection that seemed to make him the appropriate person to come to Bloomington was that, like him, my brother had also been abbot of Kumbum. Consequently, the center is now sometimes thought of as representing the Kumbum tradition in the West. Bearing in mind that Arjia Rinpoche comes from a Mongolian family, I also thought it would be fitting if the focus of the center could be extended to include Mongolian Buddhists. The result is that the center now serves not only the Tibetan community in America, but the Mongolian communities too, and has been renamed the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center to ref lect this.

Taking advantage of his newfound freedom of expression, Arjia Rinpoche, former abbot of the great monastic university of Kumbum, has compiled his memoirs in this book, Surviving the Dragon. He writes candidly about both the joys and the horrors of his life in Tibet: how he survived famine, how he rose through the ranks of lamas to work closely with the late Panchen Lama, and how he negotiated the political perils of life in Tibet to serve the Tibetan people under Chinese rule.

Whereas others have written only about their terrible experiences of incarceration and punishment under Communist rule, Arjia Rinpoche is an insider who was elevated to the top of the religious hierarchy and understood its workings from within. Nevertheless, when events following the death of the Tenth Panchen Lama and the controversial selection of the Eleventh threatened to oblige him to compromise his principles, he chose instead to go into exile.

In order to understand what is really happening in a country where the press is neither open nor free and people live in a state of constant fear and suspicion, we must rely on the reports of individuals like Arjia Rinpoche, who can now write without restraint about what he has seen, heard, and experienced in Tibet. I believe that what he has to say will be of great interest to the many people in the world who have the compassion to find common cause with fellow humans like the peoples of Tibet, Inner Mongolia, and East Turkestan who are currently living under such critical circumstances. I hope that in creating a better understanding of what is going on there, this book will contribute to bringing about peaceful change in Tibet, where an ancient people and their valued religion and culture are struggling to survive.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama

July 20, 2009

Very soon in this land [with a harmonious blend of religion and politics] deceptive acts may occur from without and within. At that time, if we do not dare to protect our territory, our spiritual personalities, including the Victorious Father and Son [Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama] may be exterminated without trace, the property and authority of our Lakangs [residences of reincarnated lamas] and monks may be taken away. Moreover, our political system, developed by the Three Great Dharma Kings [Tri Songtsen Gampo, Tri Songdetsen, and Tri Ralpachen] will vanish without anything remaining. The property of all people, high and low, will be seized and the people forced to become slaves. All living beings will have to endure endless days of suffering and will be stricken with fear. Such a time will come.

The Thirteenth Dalai Lama

Modern Chinese history can be characterized as a Tale of Three Fish. Taiwan is still swimming in the ocean: No one has caught that fishat least not yet. Hong Kong is alive but on display in a Chinese aquarium. Tibet, the third fish, is broiled and on the table, already half devoured: Its language, its religion, its culture, and its native people are disappearing faster than its glacial ice. However, although its body may be disappearing, the spirit of Tibet is still present. Hope is not yet lost.

Tibetans are not nave, nor do they have a superstitious belief in deliverance by some supernatural power. Instead they have a practical wisdom acquired from their centuries of experience with invaders who have swept in, established themselves for a short time, and then disappeared. It was common practice at my home monastery, Kumbum, that when a powerful warlord came to the gates the abbot would give him gifts such as horses, rich brocades, and rugs, so that the monastery would be spared. This was just another indignity to endure, another page in history to turn, another sign of the fundamental truth of impermanence.

Tibetan attitudes must be understood in the light of this history. Armed with pragmatism and Buddhist understanding of the nature of change, Kumbum survived. So when the Chinese Communists came on the scene in 1949, calling their occupation liberation, Tibetans thought this intruder was just another gang of bandits pounding at their door. Tibetans assumed that if treated with proper diplomacy, these invaders, too, would leave; therefore the people of Tibet showed the Chinese dragon a smiling face.

But the Communists mistook these smiles as indications that Tibetans were happy to be freed from their feudal serfdom. This misunderstanding must be clarified. Tibets limited experience of the outside world left it poorly prepared for the late 1950s. Tibetans still saw the world through local, even feudal, eyes. A totalitarian society equipped with massive military power, rigid ideology, and instant communications was beyond Tibets historic experienceand Communist Chinas interest in Tibet was no passing fancy.