About Island Press

Since 1984, the nonprofit organization Island Press has been stimulating, shaping, and communicating ideas that are essential for solving environmental problems worldwide. With more than 1,000 titles in print and some 30 new releases each year, we are the nations leading publisher on environmental issues. We identify innovative thinkers and emerging trends in the environmental field. We work with world-renowned experts and authors to develop cross-disciplinary solutions to environmental challenges.

Island Press designs and executes educational campaigns, in conjunction with our authors, to communicate their critical messages in print, in person, and online using the latest technologies, innovative programs, and the media. Our goal is to reach targeted audiencesscientists, policy makers, environmental advocates, urban planners, the media, and concerned citizenswith information that can be used to create the framework for long-term ecological health and human well-being.

Island Press gratefully acknowledges major support from The Bobolink Foundation, Caldera Foundation, The Curtis and Edith Munson Foundation, The Forrest C. and Frances H. Lattner Foundation, The JPB Foundation, The Kresge Foundation, The Summit Charitable Foundation, Inc., and many other generous organizations and individuals.

The opinions expressed in this book are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of our supporters.

Island Press mission is to provide the best ideas and information to those seeking to understand and protect the environment and create solutions to its complex problems. Click here to get our newsletter for the latest news on authors, events, and free book giveaways. Get our app for Android and iOS .

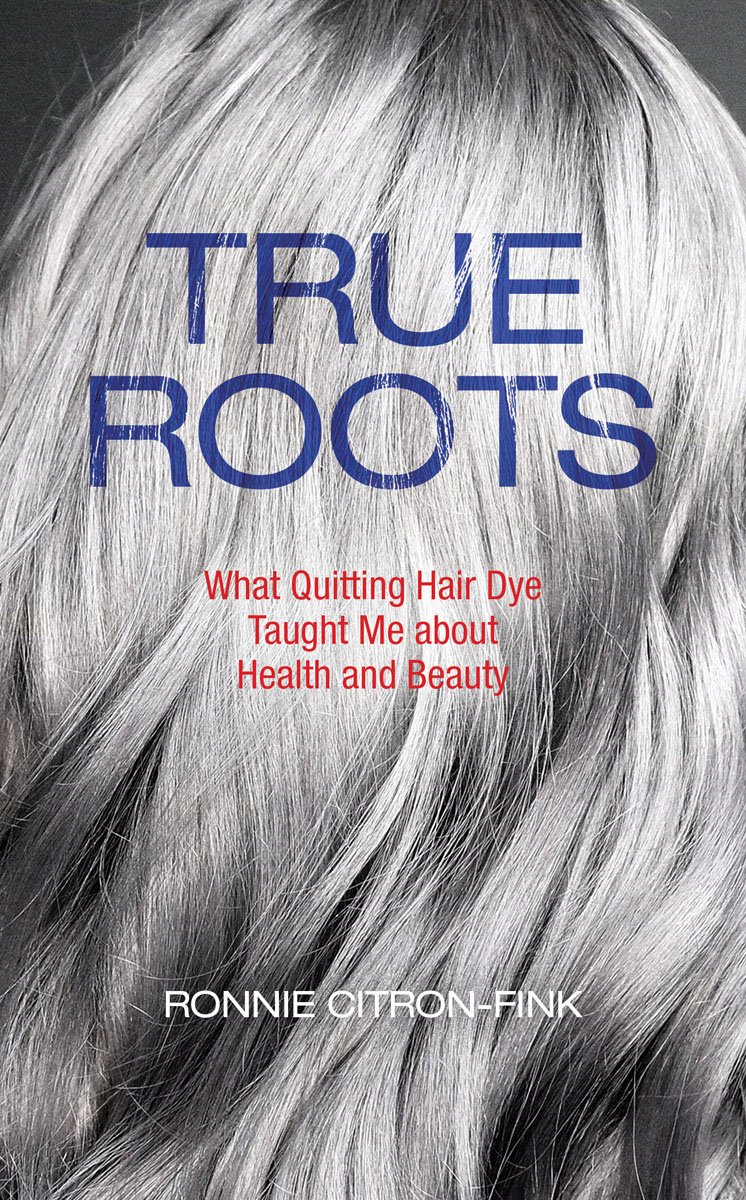

Copyright 2019 Ronnie Citron-Fink

The information in this book is not intended as a substitute for the medical advice of physicians. Readers should consult a physician in matters relating to their health.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher: Island Press, 2000 M Street, NW, Suite 650, Washington, DC 20036.

Island Press is a trademark of the Center for Resource Economics.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018967127

All Island Press books are printed on environmentally responsible materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Keywords: Aveda, Black Women for Wellness, blending, Brazilian Blowout, carcinogen, Clairol, coal-tar dyes, colorist, Cosmetic Ingredient Review, cosmetics, endocrine disruptor, Environmental Defense Fund, environmental health, Environmental Working Group (EWG) Skin Deep, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), gray hair, hair color, hairdresser, Hairprint, Henna, Just For Men, LOral, Moms Clean Air Force, para-phenylenediamine (PPD), permanent hair dye, Personal Care Products Council, Pia Grnning, purple shampoo, salon, semipermanent hair dye, silicon, silver hair, skunk line, Womens Voices for the Earth (WVE), Yazemeenah Rossi

for Ted, Lainey, and Ben

Contents

Foreword

Dominique Browning

When I was quite young, my stylish mother taught me to describe her hair color as salt-and-pepper. I found this an appealing idea, and somehow it made me think everyones hair color bore some relationship to food: hair the color of strawberries, cinnamon, oats, orwell, if I had ever eaten such a thing, I would have seized on the idea of hair the color of jet-black squid ink. As this is a book about hair and what it is costing us, in health and in dollars, to maintain its splendiferous colors, it is only natural that mothers should march right in at the beginning. It is a universal truth that mothers have an outsize influence in the way we assess and appreciate (or denigrate) ourselves.

My mothers hair began to turn gray when she was in high school, she told me, so I only ever knew her as sporting that dramatic color. The salt was bright silver, and the pepper was ink black. I recall people stopping her to ask what brand of dye she was using. To which, with a haughty sniff, she would reply, Nothing. Not that my mother was a naturalist. I dont think I ever saw her without bright red lipstick. Throughout our lives together, my own hair was among her many vexations with my sense of style. By the time I was a teenager, it was so long and unruly that decades later, my own son, watching home movies of me and my sisters, exclaimed in wondrous horror that I looked like a cavewoman.

All of which is to say: hair carries a lot of messages, sends a lot of signals. We see hair before we look into anyones eyes. When I first met Ronnie Citron-Fink, ten years ago, her hair was the jet black of squid ink, long, shiny, lustrous, and thick. She kept it dark with dye, through painstaking hours sitting in a hairdressers chair.

Ronnie had just joined me to help launch Moms Clean Air Force. We have become an organization of over a million moms (and probably lots of dads, and aunts, and grandparents too) uniting to demand clean air and climate safety for our families and for the sake of our childrens health.

One of the campaigns we focused on in our first few years was the reformation of an outdated law governing chemical safety in this country. Actually, outdated doesnt begin to describe the shortcomings of the way the United States reviews chemicals before they get into the stuff we eat, drink, breathe, and slather over our bodies, day after day after day. Thats the rub. We have systems to test small doses of single chemicals; we dont have systems to test what happens over time, when a possible carcinogen is applied daily, monthly, yearly. We dont have systems to test what happens when individual chemicals interact with one another as they are absorbed into our bloodstreams.

We are the guinea pigs for the chemical industry.

We think that because we are buying something at a store we trust, it must be safe. That if it doesnt immediately make us sick, or give us a rash, it must be okay. That our government agencies are keeping watch over usin the case of cosmetics and hair dyes, that would be the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). We are mistaken, sadly. The beauty industry is gigantic: $70 billion per year. The agency that regulates what you put on your hair to color it, and the cosmetics you put on your face to color it: tiny. And dangerously understaffed, with twenty-seven people and an $8 million budget. Nowadays, as Ronnie makes clear, the FDA, more than ever before, is mostly captive to the powerful chemical industry. Day after day, year after year, women, men, children, our babies, even, are exposed to carcinogens, endocrine disrupters, allergens. It is almost impossible to believe, but it is true.

And our hair says it all.

Ronnie and I sat together one afternoon in a meeting about toxic chemicals and the limitations of regulatory agencies. She was, as always, running her fingers through her hair. And then I noticed, suddenly, she stopped. And looked over at me, her still jet black eyebrows high, her gaze criticaland horrified. I could tell what she was thinking: what am I doing to my health by dyeing my hair? Thus began her journeyI would call it an adventurethrough what turns out to be the head-spinning maze of loopholes, dark corners, and hidden traps of a multibillion-dollar-per-year hair care industry.

Next page