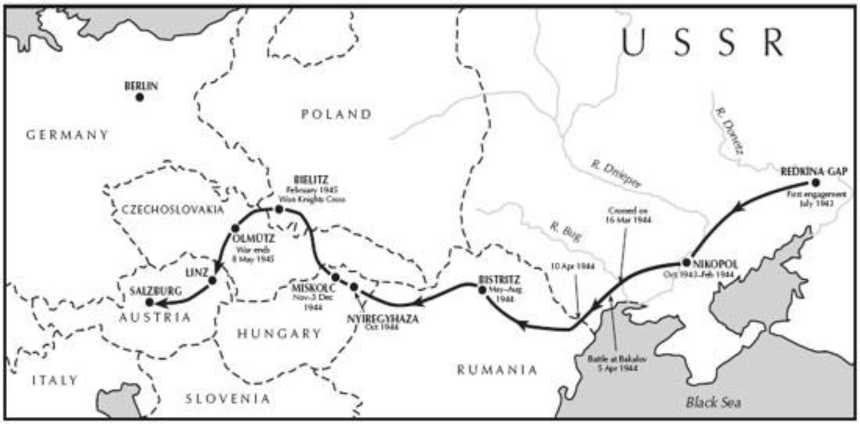

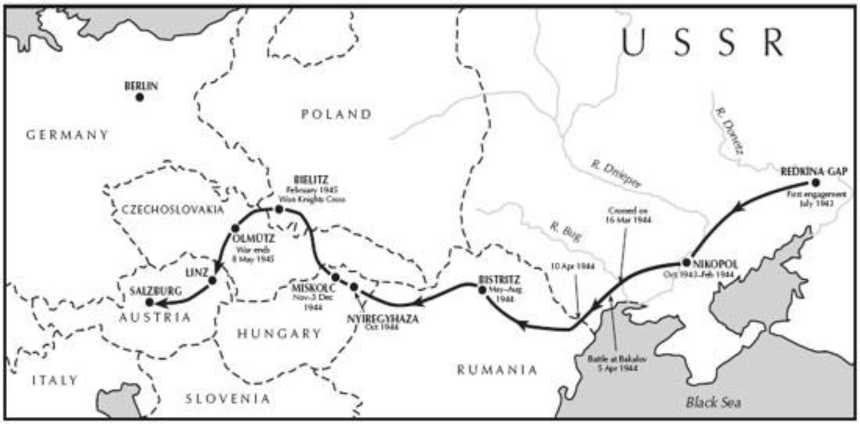

The route followed by Josef Sepp Allerberger

from the battle of Redkina Gap near Voroshilovsk, July 1943

Introduction

This book relates the wartime career of Wehrmacht sniper Josef 'Sepp' Allerberger, an Austrian conscript who served on the Eastern Front from July 1943 until May 1945. Although never rising above the rank of private, he was awarded the Knights Cross and is listed as the second highest scoring Wehrmacht marksman in the field with 257 confirmed kills.

Austrians such as Allerberger who served in the Wehrmacht had German nationality. On 12 March 1938, German forces entered Austria for the purpose of annexing the country into the German Reich. On 18 March 1938, the Reichstag passed the Law for the Reincorporation of Austria into the Reich (Reichsgesetzblatt I, p. 262, and BliV 1938 No. 12). This enabled frontier and customs posts to be dismantled, and to all intents and purposes, Austrian citizens obtained a status of nationality which rendered them liable, amongst other things, to conscription into the Wehrmacht.

This book is based largely on interviews given by Allerberger to Albrecht Wacker and others for the book Im Auge des Jagers (VS-Books, Herne, 2000), and on earlier question and answer sessions he gave, as for example in the official Austrian military publication Truppendienst (Hauptmann Hans Widhofner, 1967). The principal background source used has been General Paul Klatt's Die 3. Gebirgsdivision.

I have preferred the autobiographical form for this book since in my opinion the narrative is best cast in the first person if the manner in which information was collated enables the material to be written as a personal memoir. The biographical approach can be appropriated as a vehicle for the expression of the political opinions of authors, particularly modern German liberal authors, which are not, and never were, held by the subject, but appear to be attributed

to him to satisfy the requirements of political correctness. In the original German volume, as an aid to concealing Allerberger's identity, a pseudonym was employed, all sensitive family photographs masked, his country of origin stated as Germany instead of Austria and certain dates doctored on the grounds that 'German snipers, even in their own country, are reviled as ruthless murderers, and for this reason it is essential to protect the subject with anonymity'. Within a day or so of receiving Wacker's book I identified the subject Allerberger by briefly surfing the Internet for information on Wehrmacht snipers and accordingly I have no confidence that Wacker's precautions would be likely to baffle for long a really determined revenge-seeker.

In the Epilogue to the Wacker book, Allerberger asks the critical question, 'Was it right, what we did? Was there an alternative under the given circumstances?' One has to consider very carefully this question, for Allerberger has had the benefit of sixty years' exposure to Western propaganda that it was 'not right', and yet he is still a 'don't know'. This uncertainty has its roots in the hypocrisy of condemning one political regime for its excesses and aggression, and not the other.

The 1924 Soviet Constitution had as its aim 'one worldwide socialist Soviet Republic'. Lenin and Stalin made no secret of their desire for a second European war to establish a communist Europe. The Soviet build-up towards this end began long before they embarked upon the road in 1939 with the occupation of eastern Poland, and in 1940 the Baltic States of Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. In his recent book, The Icebreaker, Viktor Suvorov (the former military spy Vladimir Bogdanovich Resun) makes the case that Soviet military theory was based on offence and the conquest of territory 'for the world revolution'. Operation Groza (Thunderstorm), the invasion of Europe to the Atlantic, was scheduled to begin on 6 July 1941. The statement of General S.P. Ivanov, Chief of the General Staff Academy of the USSR armed forces in 1974 that 'the Nazi High Command succeeded in forestalling our troops literally two weeks before the war began' seems eloquent enough proof of this allegation, and more recently Russian academic historians Vladimir Nevezhin and Mikhail Meltiujov have found archive material that supports Suvorov's allegation.

From the earliest beginnings of the National Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiter Party or NSDAP (The Nazi Party), the primary aim had

been the destruction of Bolshevism. This was for religious reasons as well as political. The hidden religious basis of National Socialism was reincarnation without a heaven (Hitler's table talk, 13 December 1941). Judeo-Christianity was nothing but communism (Hitler's table talk, 30 November 1944) and modern Bolshevism was nothing but Christianity without the metaphysical trappings (Hitler's table talk, 14 December 1941). Hitler saw himself as the Grail knight, Parsifal, the prophet of man's rebirth in a new form, his task being to elevate mankind for the global struggle to eventually escape the cycle of reincarnation. The secret name of his Berghof residence, Gralsburg - fortress of the Grail - seems to confirm this (Hitler's table talk, 2 February 1942). Hitler's dedication to a Buddhist philosophy is obvious from the fact that throughout the Great War he carried the five works of the philosopher Schopenhauer in his gas mask case (Hitler's table talk, 19 May 1944) and knew large tracts of them by heart. He thought as a pantheist and a mystic, since he perceived God as being the sum total of all that is (Hitler's table talk, 24 October 1941), and for the raising of humanity he aimed to make the whole world vegetarian (Hitler's table talk, 11 November 1941), and believed that the advancement of science lay in its extension to include the spiritual sciences where philosophy was firmly in the foreground: he considered that the borders between the disciplines were nowhere near so clear cut as one might think (Hitler's table talk, 19 May 1944). It may well have been the intention from the very outset of Nazism to overthrow the communist system in Russia, but Hitler's plans to attack the Soviet Union were certainly firm from 1940. He appears to have had definite intelligence that the Soviet Union intended attacking all Europe in the latter part of 1941, and this was the motivation for Operation Barbarossa that year (Hitler's table talk, 17 September 1941).

Even if the evidence of the Soviet plan were cast-iron, however, Western historians would fight tooth and nail to discredit the documents simply because the West could not have an official history in which Hitler pre-empted the Soviet planned invasion of Europe while the United States and Britain supplied Russia with weapons and equipment. It is very possible that the mission of Hess in May 1941 was to bring the evidence to the attention of Britain in the hope of making lighter Germany's formidable task.

Therefore the answer to Allerberger's question, 'Were we right (to attack the Soviet Union)?' is almost certainly 'yes' on the

military-political basis: on the religious basis, the so-called Holy War against an atheist empire, another level is involved and ethics are no more applicable here than they are in deciding whether the crusades were justified.

Chapter 1

Machine-Gunner at the Ukraine Front, September 1943

I was born in September 1924. Our home was in a small village on the Austrian side of the Bavarian Alps near Salzburg. On leaving school I was apprenticed to my father, a master carpenter who ran a small workshop with a couple of employees. Notices of eligibility for conscription into the German