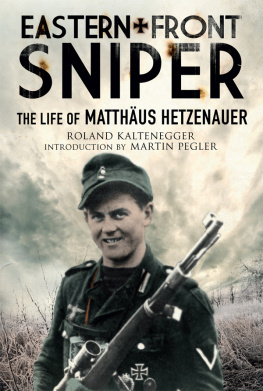

Eastern Front Sniper

Available :

Snipers At War: An Equipment and Operations History

John Walter

Forthcoming :

The Sniper Encyclopaedia: An Illustrated History of World Sniping

John Walter

Russian Sniper

Evgeni Nikolaev

Lady Death: The Memoirs of Stalins Sniper

Lyudmila Pavlichenko

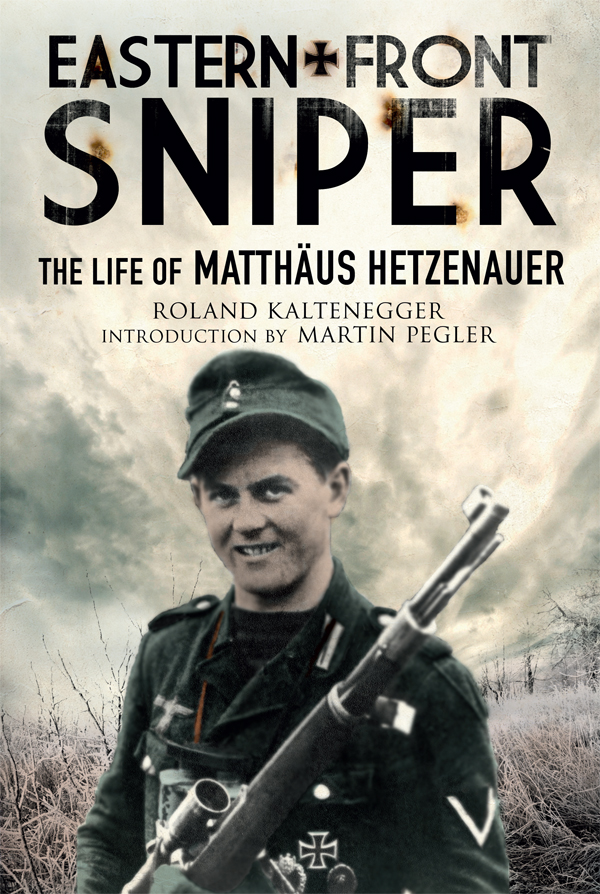

Eastern Front Sniper

The Life of Matthus Hetzenauer

Roland Kaltenegger

Foreword by

Martin Pegler

Translated by

Geoffrey Brooks

Greenhill Books

Eastern Front Sniper

This edition published in 2017 by

Greenhill Books,

c/o Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley,

S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.greenhillbooks.com

ISBN: 9781784382162

eISBN: 9781784382186

Mobi ISBN: 9781784382179

All rights reserved.

First published in German as

Gefreiter der Reserve Matthus Hetzenauer: Vom erfolgreichsten Scharfschtzen der Wehrmacht zum Ritterkreuztrger

Verlagshaus Wrzburg GmbH & Co. KG

Flechsig Verlag, Beethovenstrae 5 B.

D-97080 Wrzburg, Germany

www.verlagshaus.com

Translation Lionel Leventhal Ltd, 2017

Martin Pegler introduction Lionel Leventhal Ltd, 2017

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

Foreword

Matthus Hetzenauer, Scharfschutzen

WHEN I WAS INTERVIEWING a high-scoring Second World War British sniper some years ago, I asked what sort of men made the best snipers. He told me that they were not the life-and-soul of the party type and in the unlikely event one was there at all, he would be the quiet one sitting in the corner, probably drinking fruit juice and observing everyone else. Extrovert snipers were a liability to themselves and their comrades and seldom had a long service life. Snipers can generally be typified as reflective, observant men, who deliberated carefully about things before acting. It was how they survived. Sniping is the most physically and mentally demanding of any military role and in World War Two sniper casualty rates were around 80 per cent. The fact that Matthus Hetzenauer became the highest-scoring Axis sniper and lived to tell the tale says a great deal about the sort of man he was. Much of the detail of his life after the war remains unknown, although his family tell of a quiet man who loved the Alpine region in which he had been brought up, but did not talk about his experiences. However, there must have been iron under his skin for not only did he survive the bitter Eastern Front campaign, but remarkably also the privations of five years of captivity and forced labour. Some idea of the harshness of life in the Soviet prison camps can be seen from current estimates that of the near three million Germans captured by the end of the war, almost one million died in captivity.

As is so often the case with snipers, personal details about their lives are sparse; very few wrote autobiographies and those who did often fictionalised their accounts, in part to protect others, but also to play down their own role. The fact is that probably 99 per cent of snipers have not left any written testimony as to their involvement in the fighting. Even long after the war, the majority were extremely reluctant to talk about what they did. Those Allied snipers whom I have interviewed spoke to me only under a mutual understanding of the strictest confidence and much of what I have been told has never been published out of respect for their wishes. Matthus Hetzenauer was no exception. Although his compatriot and fellow Austrian sniper Josef Allerberger did collaborate with Dr Albrecht Wacker to write a fictionalised account of his life in 2000 ( Im Auge des Jgers ) this was a very rare event, but Allerbergers war service is interesting in that it parallels that of Hetzenauer to an extraordinary degree for they served in the same division and on the same battle fronts and they knew each other well. Thus they would both have seen and experienced much the same events. It is believed that Hetzenauer only ever gave one interview on the subject of his shooting, in the magazine Truppendienst (Troop Service) in 1967, and I have based much of the information below on his comments.

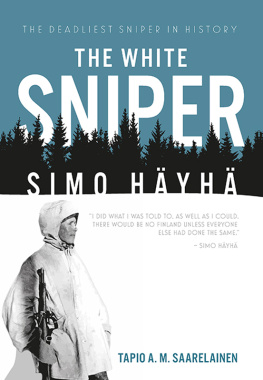

The Rifles

A technical explanation of the sniping war on the Eastern Front might be of interest to the reader, as it saw the greatest amount and the most deadly sniping of any theatre of the whole war. Both sides began the fighting with the minimum of sniping equipment, although the Soviet Army was initially the better equipped and trained of the two. This was in part due to the appalling losses inflicted on it during the brief Winter War against the Finns between November 1939 and March 1940. The Finnish Army fielded a large number of snipers and expert riflemen, against whom the Soviets had little or no defence. It was somewhat ironic that the rifles the Finns used were actually Soviet-designed Mosin Nagants, albeit a re-worked variant called the M.27, mostly assembled in Finland with high-quality barrels supplied by Swiss and German companies. Some were equipped with telescopic sights, but many were not. In the hands of the expert hunters who had transferred their skills to the Finnish Army, this mattered not a bit. Indeed, many snipers regarded the telescopic sights as a hindrance in the bitterly cold conditions. This was due to several factors: a scope needed to be kept warm, often in a pouch worn next to the snipers body, but when fitted to a rifle and used, sudden exposure to the cold would result in it instantly fogging up, rendering it useless. The adjustment drums could freeze solid, as could the reticules (crosshairs), and the mounting screws become brittle in the cold. The highest scoring of all the Finnish snipers, Simo Hyh, or as the Russians called him Belaya Smert (White Death), achieved the majority of his 505 official kills with an un-scoped rifle.

An early-war photo of a German sniper making use of a captured Mosin Nagant/PU scope combination .

The Russians were not devoid of snipers or sniping rifles during the Winter War, however; they did have small numbers of trained men equipped with a scoped version of the venerable Mosin Nagant M1891/30 rifle, but there were insufficient of both to deal with the Finns and the snipers themselves were poorly trained. The rifles were fitted with a 4-power scope known as the PE (with a later improved model called the PEM), which had been copied from a World War One German pattern made by Emil Busch AG, and these had been in production since 1931. It was physically a comparatively large instrument but it did have excellent optics.

A Mosin Nagant rifle with the early pattern PE scope . NRA

However, it was clear after the war that there were huge gaps in the preparation and employment of Russian snipers. As a result they set up a massive training programme and embarked on the production of very large quantities of scoped rifles. Germany meanwhile had been held back by the post-World War One restrictions imposed upon it by the Versailles Treaty, which severely limited the development and production of military weapons, naturally including sniping rifles. The Germans managed to evade this to some extent by retaining numbers of Great War-era Gewehr 98 (Gew.98) sniping rifles. Experience during the war had shown that these original long-barrelled rifles were too cumbersome in combat and the extra barrel length achieved little in the way of improved accuracy. As a result, most of them were modified postwar by being shortened to carbine (K98a) configuration by having six inches (150mm) lopped off the barrel, bringing it down to a more manageable 23 inches (590 mm).