MacLehose Press

An imprint of Quercus

New York London

2017 Lyuba Vinogradova

English translation 2017 by Arch Tait

Introduction 2017 Anna Reid

Maps Bill Donohoe

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to .

e-ISBN 978-1-68144-283-9

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, institutions, places, and events are either the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual personsliving or deadevents, or locales is entirely coincidental.

www.quercus.com

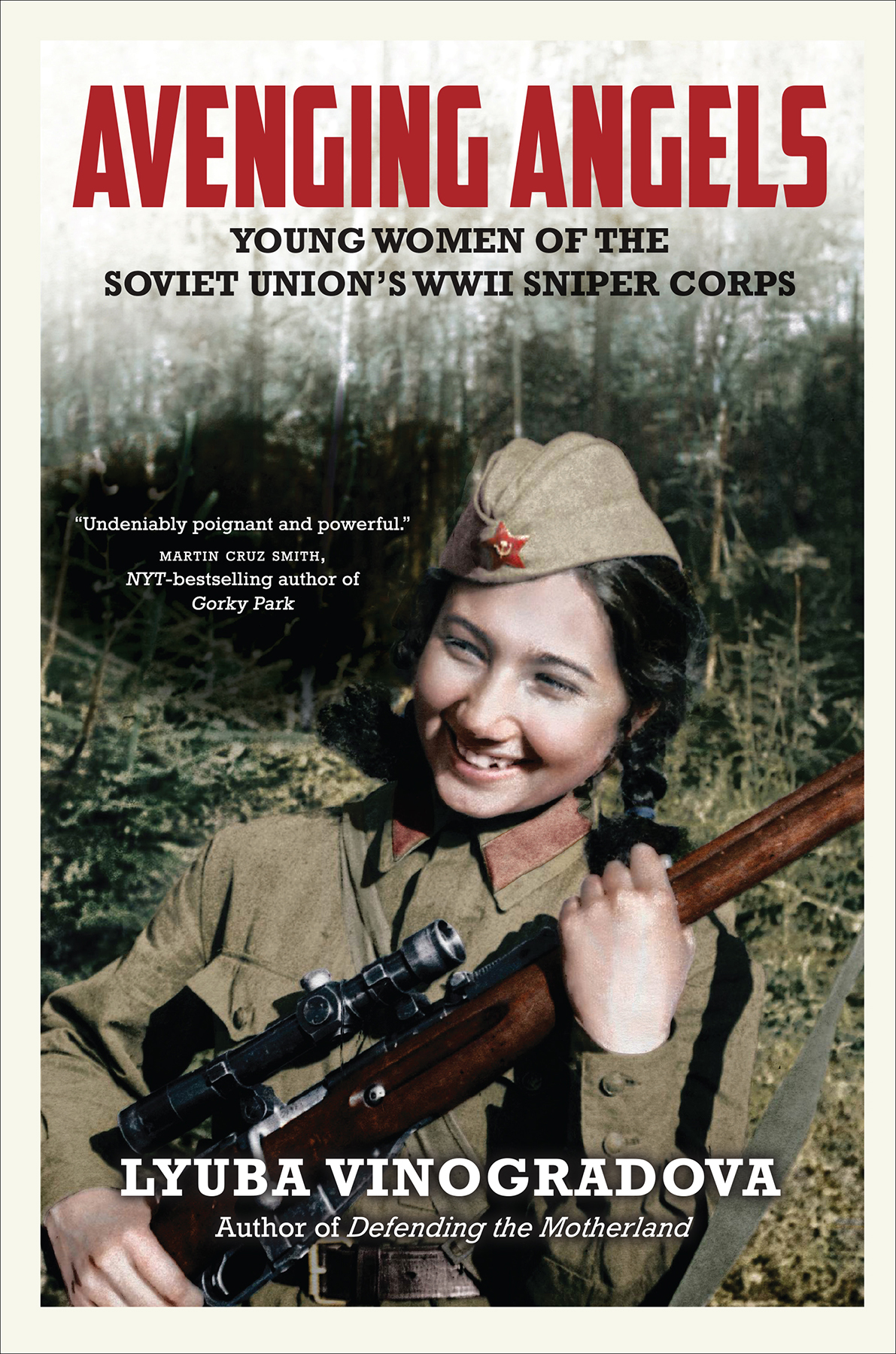

By the same author

A Writer at War: Vasily Grossman with the Red Army 19411945 (2005) (with Antony Beevor)

Defending the Motherland: The Soviet Women Who Fought Hitlers Aces (2015)

In memory of my friend, Anna Sinyakova (Mulatova)

List of Illustrations

Introduction

Anna Reid

The Soviet Union sent more women into combat during the Second World War than any other nation before or since. Estimates vary widely, but one can safely assume that a minimum of 570,000 women served in the Red Army during the course of the war, and more likely 700,000800,000. Add in female partisans and volunteers to civilian militias, and the total rises to around a million.

In the chaotic weeks following the German invasion of June 1941, Soviet women, like men, volunteered in huge numbers, queuing to register for whatever war work was available. Though an estimated 20,000 were able to join up immediately, simply by personally approaching local commanders, the majority were initially channeled into factory or civil defence work. Full-scale conscription of women into the military did not begin until March 1942, to make up for enormous losses suffered during the initial German Blitzkrieg and the defences of Moscow and Leningrad. By 1943, however, women were fully integrated into all services. Most acted in relatively traditional roles: as nurses, secretaries, drivers, telephonists, signallers, mechanics and cooks. But a substantial minority took up arms: as anti-aircraft and machine-gunners, sappers, scouts, bomber and fighter pilots and aircrew, snipers, tank crew and ordinary infantry. They won promotion as the war progressed, so that by 1945 female platoon, company and even battalion commanders were common enough to attract little comment.

Nowhere else did women fight in anything like these numbers, if at all. In Britain, though over half a million women wore uniform, the only ones allowed actually to operate weapons were 56,000 Ack-ack girls who manned mixed-sex anti-aircraft batteries from the summer of 1941 onwards.

Though the girls quickly proved their worth, they met with considerable official opposition, and remained symbolically banned from triggering their guns firing mechanisms. Prompted by the British example, America secretly trained 395 female anti-aircraft gunners from December 1942. But the experiment was abandoned within a few months, for fear, according to the head of army personnel, that neither national policy nor public opinion are yet ready to accept the use of women in field force units.

In Germany, the National Socialist ideology of children, kitchen, church for women was so strong that they were not fully mobilised even into civilian war work until 1943. They were not drafted into the army until 1944, and as late as November of that year Hitler issued an order reiterating that no women be weapons trained. Three months later, with the Red Army at the gates of Berlin, he finally authorised the creation of an all-female infantry battalion, with the aim of discouraging desertion from the crumbling Wehrmacht. It had not yet formed when Germany surrendered.

Various explanations have been put forward for the Soviet Unions unique willingness to use women in combat. Cultural and historical factors may have played a part: the long roll-call of female revolutionaries under the last two tsars, the tens of thousands of women who served on the Bolshevik side during the Russian Civil War, the Soviet constitutions (theoretical) embrace of sexual equality. The overwhelming factors, however, were probably simply Soviet womens own strong incentive to fight they had seen their own country invaded, and friends and family killed and the militarys desperate need for extra manpower, following near-overwhelming losses in the opening months of the war.

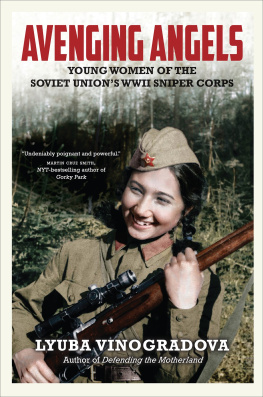

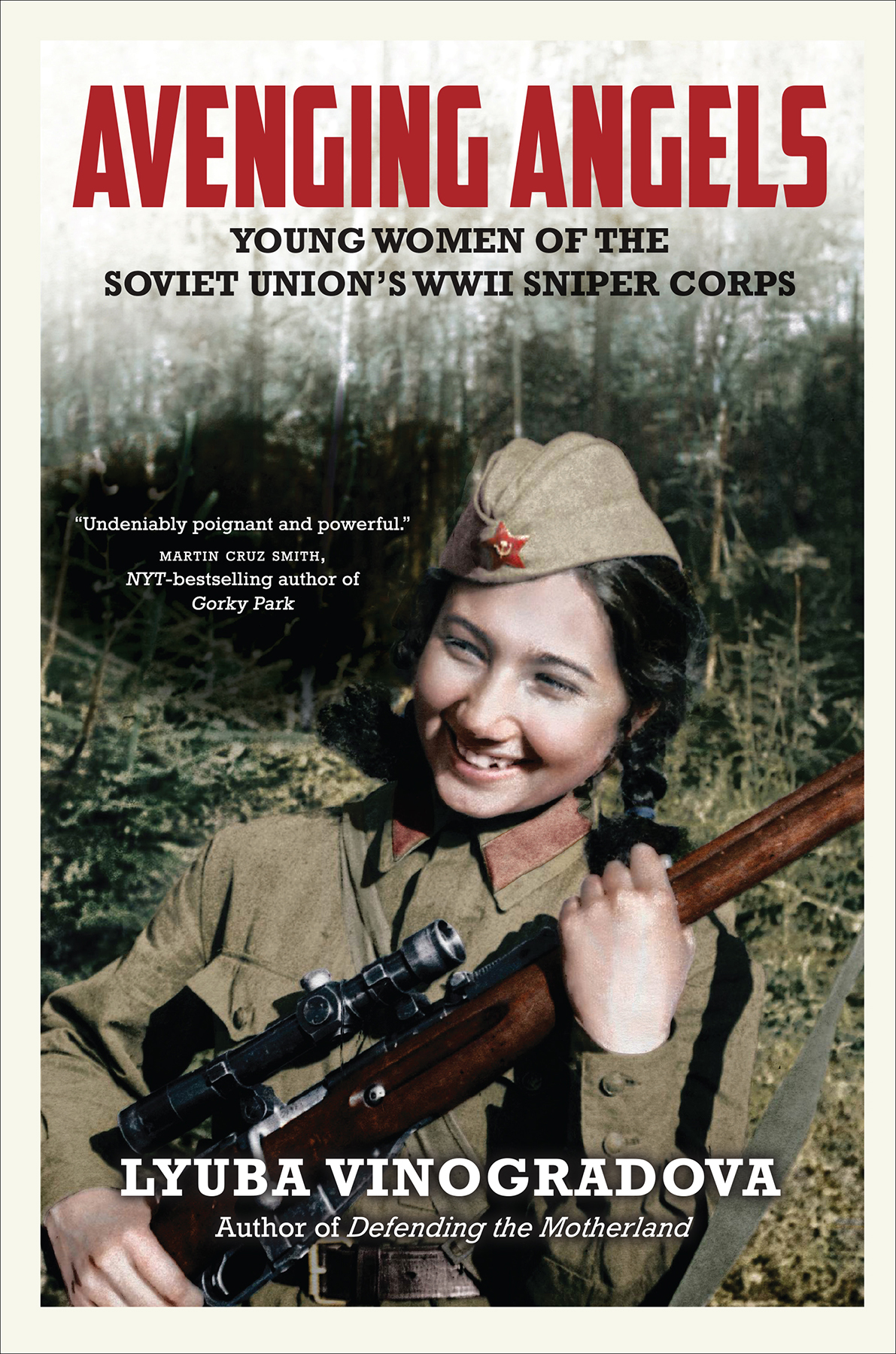

Avenging Angels is a companion volume to Lyuba Vinogradovas earlier Defending the Motherland: The Soviet Women Who Fought Hitlers Aces. Both centre on her interviews with women who took on some of the wars most high-profile combat roles as fighter and bomber pilots, and as snipers. Vinogradovas concern is not to assess their contribution to the war effort, nor to Soviet gender politics, but to capture their individual stories, the particular lived experiences that are left out of conventional top-down military history writing. What, she wants to know, was being a sniper on the Eastern Front actually like?

Even for young women raised amidst the turmoil and hardships of Stalins Russia, joining the army came as a social, emotional and physical shock. At training school, peasant girls from dirt-poor villages had their cherished braids lopped off, and encountered tea and bed linen for the first time in their lives. Gently raised students from Moscows Conservatoire found themselves taking orders from illiterate Tatar shepherds. Once at the front they had to learn to deal not only with enemy fire, but with cold, gnawing hunger, lice, oversized boots, rudimentary sanitation and sexual assaults by drunken male officers.

Like their male counterparts, most female snipers found their first kills traumatic, particularly because they were administered not during the heat of battle, but during periods of static warfare, when the victim emerged from his trench to wash or clear snow. Some were transferred to non-combat jobs, but the rest grew used to killing, competing to increase their tallies. During assaults they doubled as infantry, running forward and firing with the men, or as medics, moving the wounded and administering first aid. Many, of course, were killed or wounded themselves. Overall casualty rates are unknown, but judging by the sample Vinogradova gathers here, they were very high. Most of her interviewees had lost multiple sniper partners by the end of the war.

Next page