Introduction

Just moments after I gave birth to our daughter, my partner, Faith, scooped up the baby, cooed into her squishy newborn face, and said, Hello there. Im your mommy.

I wanted to kill her. Faith, that is.

Granted I was doped up on hormones, painkillers, and fatigue. Granted I had been up all night struggling to learn how to place my cracked and excruciating nipples into our childs rosebud of a mouth so that I might oer up every ounce of nourishment and energy I had left in me. Granted I had not had an Advil, a glass of wine, or sushi in a very long time. Still.

Who was Faith to call herself Mommy?

I wanted to be Mommy, the only momm y. Yes, we both had planned for the birth of our child; yes, we both had been present and accounted for at her conception; yes, we both were women. But hadnt I earned it?

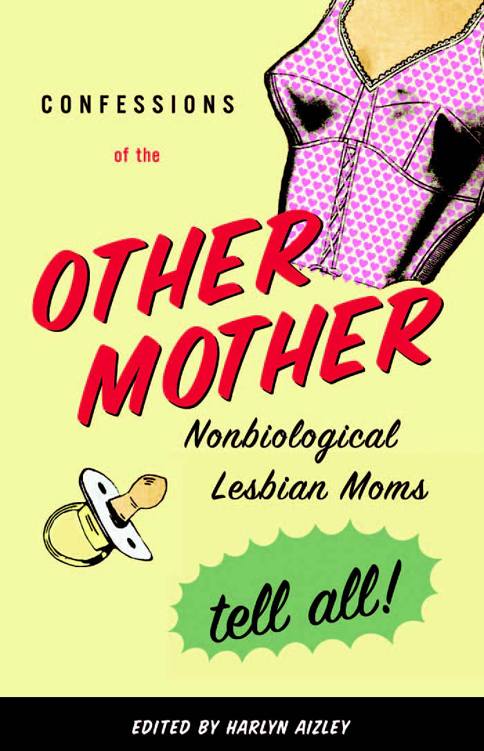

And so we w ere o, into the beautifulthough often unexpectedly complexterrain of two-mommy parenting. To extend the metaphor, we soon learned that this new land that was our home, while frequented by many, remained virtually uncharted. Where were the guidebooks? Where were the stories from other settlers? As a new biological mother, I had at my disposal mommies groups, lactation consultants, my obste trician, and my o wn mother, all of whom wished to share advice, sup port, and stories of their own similar initiation into parenthood. But where was Faiths experience? Where were the anecdotes from women who, like Faith, had opted to postpone or forgo their own birthing expe rience to assist t heir female partner in hers? Where were the tales of life at home raising another womans child, a child who is also your own, but

i x

in a wholly dierent way? Faith needed them. I needed them. And one day our daughter would need them, too.

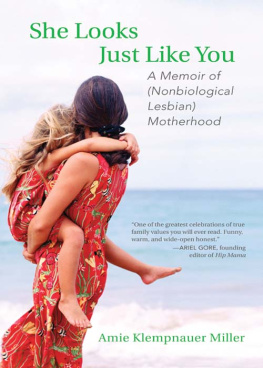

A search for literature on the subject revealed a sad wealth of horrid and fearsome custody tales, news, and scientific reports about the battles between women over their children, made all the more painful and divi sive as they had the added pressure of creating precedence for custody cases yet to come. There were stories about states that forbid adoption by same-sex parents, and harrowing tales of a biological mothers relatives exercising their assumed blood rights over those of a nonbiological mother. While valid and critical to our understanding of the social and political impact of same-sex parenting, these stories provided little in the way of support and/or relief. They emphasized the need for adequate le gal safeguard swills and powers of attorney, second-parent same-sex adoption when possiblebut shed no light on the everyday experiences of the nonbiological mother. Legalities aside, lacking were what we needed most: tales from the front lines of nonbiological motherhood, optimistic, funny stories of otherwise happy and contented lesbian moms struggling to make sense of their family structures at the play ground, at P TA meetings, in car pools listening to three-year-olds discuss what it means to have two moms, or when slamming headlong into unanticipated maternal longingstheir own as well as those of their bio mom partner. (As far as this bio mom was concerned, the reluctance to share the title mommy was just the tip of my biological iceberg).

The narratives in this anthology are stories from these settlers. They are anecdotes about what it means to be a macho butch politico more ac customed to passing as a man than as a mother, or a woman grieving her own infertility while supporting a partner who has easily become preg nant for the second time. They are honest, candid confessions of jealousy experienced while watching a partner breastfeed, and exasperation at having to come out publicly a dozen times a week in response to the ques tion, W hos the daddy? These are the stories from childbirth class, from the nursery in the middle of the night and the tot lot first thing in the morning. They are humorous and poignant, exquisitely personal and deeply reflective.

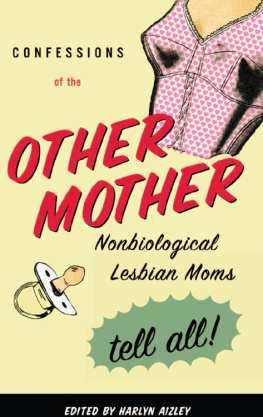

Confessions of the Other Mother is not a guidebook, because as any of the women featured here will tell you, there are no universal rules for two-mommy parentingor any parenting, for that matter. Its more like a campfire around which a nonbiological lesbian mom can listen to tales told by a bunch of gals making the same journey as she. Its a place where that same exhausted mom might at last slap her knee and exclaim, I know exactly what you mean!

The essays that make up the first part of the book, Birth, Babies, and Beyond, explore the experience of nonbiological motherhood from con ception to r aising children. Almost every author addresses the issue uni versal to lesbian c ouples desirous of biological children: Which one of us will get pregnant? But from there they diverge, with some women using the brief telling of a moment in their lives as parents or parents-to-be to convey the emotional significance of their role: watching a partner breastfeed, battling insensitive bureaucracy in the maternity ward. Oth ers consider the place in society their mothering has created with longer pieces that capture both the personal and political sides of nonbiological mothering. Still others challenge the presumptions of language, suggest ing that a ll female parents need not be mothers, and that words like non-biological and non-birthmother are negatives that do no justice to the very positive fact of a womans parenting.

Because lesbians have at their disposal varieties of parenting that far exceed those available to couples sporting opposite genders, I have in cluded two shorter sections. Mucking with the Stu gives voice to women who have straddled both sides of the mothering fence. In it we hear from two biological moms whose partners chose to become preg nant, as well as from two nonbiological mothers who later birthed a child. In Arriving When the Show Has Started, a lesbian stepmom shares her story of picking up the parenting pieces upon uniting with a recently divorced woman and her two sons.