BEACON PRESS

25 Beacon Street

Boston, Massachusetts 02108-2892

www.beacon.org

Beacon Press books

are published under the auspices of

the Unitarian Universalist Association of Congregations.

2010 by Amie Klempnauer Miller

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

14 13 12 11 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper that meets the uncoated paper ANSI/NISO specifications for permanence as revised in 1992.

Portions of this book, in slightly different versions, have been previously published as Babymaking, Salon.com, August 11, 2004; New Day, Neurosis, Brain, Child (Winter 2005); Not a Mommy, Yet Not a Dad, Brain, Child (Winter 2006); and Watching, in Confessions of the Other Mother: Nonbiological Lesbian Moms Tell All! ed. Harlyn Aizley (Boston: Beacon Press, 2006).

The names of some people in the text have been changed, as have the identification numbers of all sperm donors mentioned.

Text composition by Wilsted & Taylor Publishing Services, Oakland, CA

Love Will Guide Us 1985 Sally Rogers, Thrushwood Press Publishing. Used by permission of Sally Rogers, Thrushwood Press Publishing.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

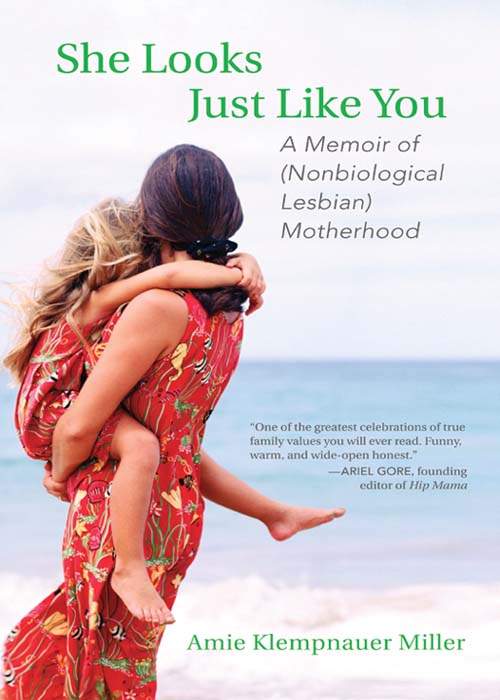

Miller, Amie Klempnauer

She looks just like you : a memoir of (nonbiological lesbian) motherhood / Amie Klempnauer Miller.

p. cm.

ISBN 978-0-8070-0151-6 (paperback : alk. paper) eISBN 978-0-8070-0470-8 1. Miller, Amie Klempnauer. 2. Nonbiological mothers United States Biography. 3. Lesbian mothers United States Biography. 4. Gender identity United States. I. Title.

HQ75.53.M65 2010

306.8743086640973 dc22 2009029937

To Jane, to Hannah

ONE

Babymaking

[I]

JANE AND I ARE STANDING in our very pink bathroom, staring at the two very blue lines on the pregnancy test stick in Janes hand. Jane took the test precisely when she wasnt supposed to: in the evening, after dinner, immediately after drinking a large glass of lemonade. She is supposed to do it first thing in the morning, when her body, if it is indeed pregnant, will have had sufficient time to store up enough undiluted human chorionic gonadotropin, that telltale pregnancy hormone, to trip the test line on the stick into blue territory. But she couldnt wait, and it didnt matter. The line on her stick turned blue immediately, a birds egg, summer sky blue that left no room for doubt. Shes not only pregnant, she is decisively pregnant. After eighteen years of just the two of us, we are going to become three.

I knew it, Jane says. On some level, I did too. For the past several days, she has come home from work exhausted and voracious. Either she was pregnant or she had developed a severe metabolic disorder. But even though I suspected a positive result, I am still wowed. I feel disoriented, as though the journey from one blue line to two has played out cosmically, bridging the time-space continuum. It feels like magic. Maybe it is.

Pregnancy is always hypothetical until it happens. Until this moment, pregnancy has stayed at a tantalizing, but safe, arms length. Now it is here, in our bathroom, hugging us like an unfamiliar and overly affectionate aunt. I gape at Jane. I can scarcely believe that her body has already begun the alchemy of transforming proteins and hormones into a new body, a new person. I am stunned by the very notion that we are actually going to be mothers, not just crabby armchair observers kvetching about how children need bedtimes and how kids today dont have any boundaries.

I stare at our faces in the mirror. We look the same as we did before dinner, which strikes me as odd. We should look different, I think. We should look pregnant, or at least expectant. I take the test stick from Janes hand and study it, checking to make sure I didnt somehow hallucinate the result. Theyre still there: the control line and the one that mesmerizes me, the test lineour blue line, our baby.

Thats my family, Jane says, shaking her head. Wave a little sperm at us and we get knocked up.

This is not how we thought it would happen. Two weeks ago, I went with Jane to the fertility clinic where she was inseminated. It was the same clinic where I had gone month after month for a year and a half, trying to conceive. The same magazines with the same articles about safe exercise during pregnancy and the virtues of breastfeeding lay on the end tables in the waiting room. The same nurse who had repeatedly inserted one mans sperm after anothers into me now inseminated Jane. Everything, in fact, was the same except that, this time, I sat in a chair and watched as my partner lay on the exam table, her sock-covered feet lodged in the metal stirrups. In the weeks prior to the appointment, Jane had been ambivalent about whether I should come along or not.

Its just a medical procedure, she said. She was right, in one sense. After ten or twelve inseminations of my own, the process became increasingly medicalized, even routine. I began to go to the clinic by myself, stop in for a quick insemination, and then drop by the coffee shop for a scone and some tea before heading to the office. I would call Jane to report on how it went, but there seemed little reason for her to tag along time after time. This was different, though. It was Janes first try, and even though inseminating with donor sperm is kind of like going on a blind date chaperoned by a nurse, I wanted to be there.

Its not like youre going in for a Pap smear, I said. Anyway, I dont want to tell our kid that I was in a meeting at the moment of conception.

So, along I went. Jane lay on the table draped in a paper sheet, her feet pointed northwest and northeast. The nurse adjusted the light over Janes hips, inserted the speculum into her vagina, and peered inside.

Youre looking great, the nurse said. Lots of good mucus here. Thats wonderful.

Then she looked at me and offered, Do you want to see?

Uh, no, I said. Thats a lesbian moment I dont need to have.

The nurse navigated the loaded catheter through Janes cervix and into her uterus, where she deposited the sperm. She adjusted the exam table, elevating Janes hips six inches so that gravity could help the sperm on their journey. As she left the room, she waved her fingers in the air.

Good luck! she said cheerily.

Jane settled in to wait the prescribed ten minutes, presumably enough time for the sperm to find their way.

Did it hurt? I asked her.

Not really, she said. A little pinching, but not bad. Insemination is a remarkably simple process, really, if also an unsentimental one. Once the nurse confirms that the number of the donor listed on the vial of sperm is, in fact, the number of the donor whose sperm we ordered, she just loads up the catheter and inserts the goods. The only real reason to do it in a doctors office rather than at home is that the nurse can get the sperm all the way into the uterus rather than just leaving it in the vagina, thereby raising the chances that at least one sperm will find its way to the egg.

Still, I had little expectation that anything would come of this visit to the clinic. I had to try twenty times before ultimately conceding defeat, so I figured Jane would need to try at least three or four times before hitting the target. I counted out the months, estimating when she might reasonably get pregnant. It was June, so September, I figured, maybe October.

Jane rubbed her hand on her abdomen.

Are you having cramps? I asked quickly. I had a fair amount of cramping after my first fruitless insemination, my cranky uterus upset about the prodding of the catheter.