Reflections on my Work with Frank Pierce Jones in light of my other experiences with the Alexander Technique

by Joe Armstrong

Novis Publications

Foreword

To my knowledge, I am the only Alexander teacher to have worked with Frank Pierce Jones both before completing the full Teacher Training and very extensively afterward. Because Frank is so widely known for his writings and research, I hope that describing some aspects of my association with him in the context of my other experiences of Alexander teaching and teacher training might be of interest to the larger Alexander community.

The following article on my early experiences with the Alexander Technique and Alexander teacher training was first circulated privately to colleagues. Subsequently, I was asked if it could be published on the websites www.alexanderstudies.org and www.mouritz.co.uk for which it was edited, respectively, by David Gibbens and Jean Fischer and published on those websites in 2016. This electronic version by Novis Publications in 2017 is a slightly more elaborate one that also incorporates an addendum containing an exchange of letters on the subject of teacher training that I had with Walter Carrington. I discovered these letters among my papers quite recently, and because of their relevance to the subject of my article, I have accepted the suggestion from Novis of connecting these to it now. I am therefore grateful to Novis for bringing out this new and expanded version.

Special thanks to Jeffrey Mitchell for his extensive editing help, and to Chariclia Gounaris, Vivien Mackie, Joan Murray, Alexander Murray, and Sue-Ellen Hershman-Tcherepnin for their invaluable corroboration, input, and enthusiasm for this piece.

Joe Armstrong

Boston, 2017

Early private lessons: 196569

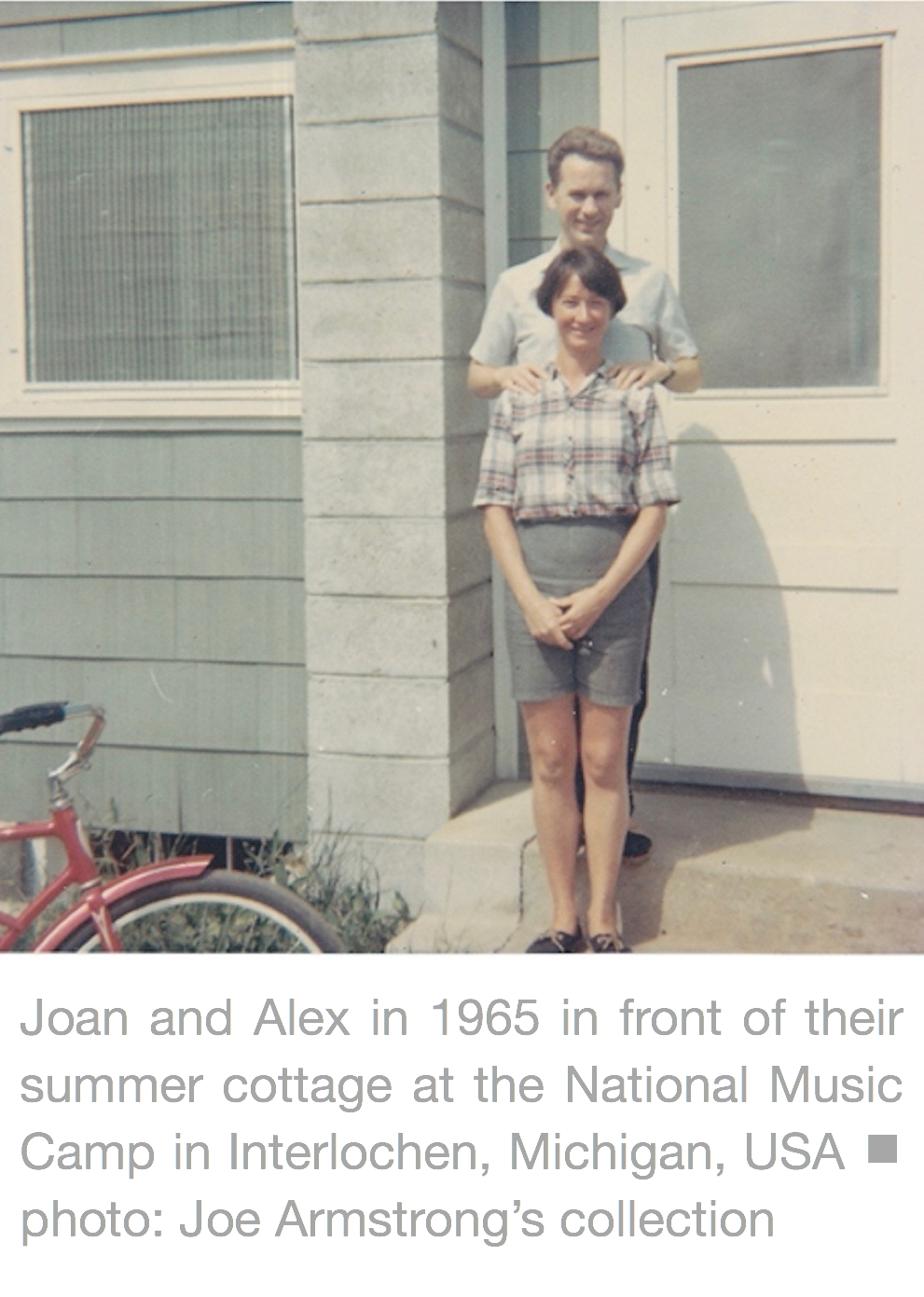

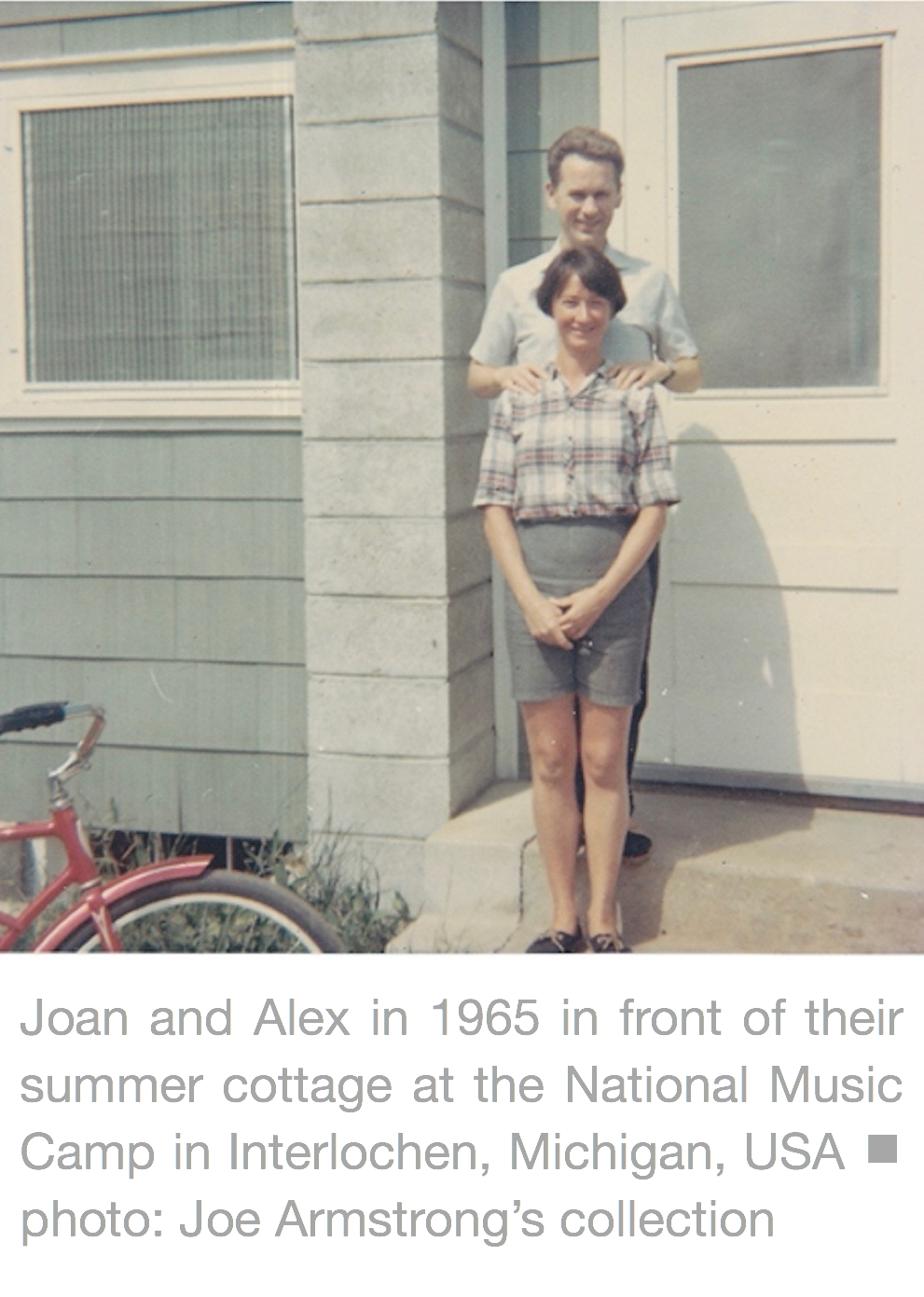

My first experience of the Alexander Technique came during two summers of nearly daily private Alexander lessons, starting in 1965, with Joan Murray at the National Music Camp in Interlochen, Michigan. I also had lessons there with Walter Carrington during his teaching visit in the summer of 1966. Some years before she came to Interlochen, Joan had trained with Walter, whose training course also included as principal teachers his wife, Dilys, and Peggy Williams, a very exacting first-generation teacher. Walter, a no less exacting teacher, had been Alexanders assistant in training teachers after World War II until Alexanders death in 1955. I had learned from Walter, Joan, and her husband, Alex, that Frank was considered the most prominent American Alexander teacher who had trained with Alexander and his brother, A.R., while they taught in the U.S. during World War II. So I made it a point to have as many lessons as I could with Frank during 1968 and 1969 while I was serving a three-year enlistment in the Army Field Band, a touring concert unit commanded by the Pentagon. This was just before I went to England in September of 1969 to attend Walters three-year teacher-training course.

Those early lessons with Frank were somewhat of a contrast to the lessons I had already had with Joan and Walter, and I found them a bit puzzling from an intellectual point of view. But the psychophysical experience I received from Franks hands seemed to be in the same general ballpark as what I had received from Joan and Walter. The chief differences were that Frank didnt maintain a more or less constant contact with his hands on me, as Joan and Walter had. And Frank didnt require me to be stationed at a particular chair chosen for the lesson, which, of course, is the traditional format for teachingoften combined with lying-down work on a table. Nevertheless, Frank did include guiding me from sitting to standing and back to sitting a number of times during each lesson within the context of walking me around to various chairs in the room. Often, while I was seated, he would continue working on me for some time while he sat facing my left side [1].

The essential difference with Franks lessons, though, was that he conducted them more as a social visit than as a special Alexander teaching session. The visit was focused chiefly around having a conversation, primarily about Alexander-related concepts and topicsa conversation in which Frank did most of the talking [2]. He saw pupils in the drawing room of the gracious and spacious apartment in the historic six-family houseThe Lowellwhere he and his wife, Helen, lived in Cambridge at 33 Lexington Avenue not far from Harvard. The room was decorated very tastefully with art work, different styles of chairs, a settee, small tables often with a pot of blooming flowers on one of them, lamps, a bookcase, and a high bureau that had drawers and various objets sitting on it. Frank would usually start working on me with his hands right where

we had been standing conversing after we entered the room. This gave the situation the feel of a predominantly intellectual exchange that coincidentally involved his putting his hands on me from time to time to enhance the working of my Primary Control as part of illustrating a point that had come up in our conversation. This approach to a lesson served to keep it from being mistaken for some type of physical therapy or posture and movement training.

Frank had no long table to use for giving pupils lying down work, and I think there were several reasons for this. One was that Franks training with F.M. and A.R. Alexander probably didnt involve much table work, if any, because there probably were no tables of the right size in the places where they taught while they were in the U.S.like the Hotel Braemore in Boston, the Whitney Homestead in Stow, Massachusetts, and the Media Friends School in Pennsylvania. Also, I assume that the Alexander brothers were so adept with their hands that they could bring about quite substantial changes through chair work aloneas was Walter Carrington, although he did have a table in his teaching room in case he found that a particular pupil or student needed lying-down work. But I think the main reason Frank didnt want to do table workor to create a special Alexander lesson spacewas because his chief interest and concern always seemed to be to make the Technique as appealing as possible on an intellectual and philosophical level to nearby Harvard, MIT, and Tufts faculty and other members of the academic, medical, and scientific professions. I thought that Franks cultivation of this perspective was probably due to his own academic orientation as well as to his appreciation for John Deweys views on the Technique and its potential to influence the fields of education and philosophy.

Since Frank had been a Classics professor before coming to do research on the Alexander Technique at the Tufts Institute for Psychological Research, his language was far more erudite than I was accustomed to in the performing arts. I sometimes had trouble absorbing what he said during those early lessons simply because his vocabulary was so unfamiliar to me and almost everything he said seemed to be abstract or indirect, rather than statements of what he actually thought, believed, experienced, or wanted me to understand. He would use words like ratiocination and proprioception.words Id never heard before, even though I had been carefully studying Alexanders four books while riding the bus on the Field Bands long concert tours. So, for me, there was a gulf between what I received from Franks hands and what he was telling me in wordsas if I had undergone two separate, but somehow related, experiences: one conceptual or intellectual, and the other sensory.