Foreword

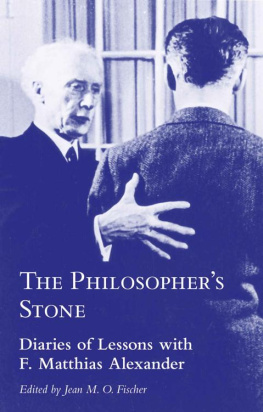

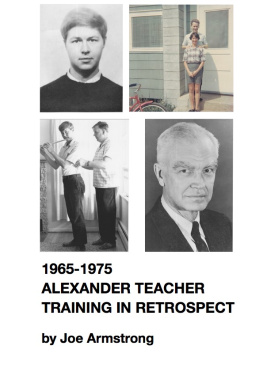

The memoir covers the period of my training at CTC (Constructive Teaching Centre, then situated at 18 Lansdowne Rd., Holland Park) from September 1964 to December 1967 and is in fulfilment of Jean Fischers request for historical material regarding training in the 1960s. At the time of receiving Jeans request (October 2016) Jean was still in charge of the Walter Carrington Archives at CTC. More precisely, his request was for general memoirs, observations, and impressions of what it was like to train back then, and he asked me to say whether or not we had any lectures on anatomy or physiology, and if games were in use what they comprised.

Capturing the spirit of the time

Memory, it is true, often plays small tricks which tend to embellish or to distort the past. But events that made a profound impact on ones mind frequently retain much of their original and authentic import and flavour. G za Vermes, The Story of the Scrolls

I joined Walter Carringtons training course at Lansdowne Road in 1964 at the age of 20nine years after F. M.s death. Walter once said to me: You would have liked F.M. meaning, I suppose, You would have appreciated the originality of his character and the way he looked at things. I did not have the good fortune of meeting the Master himself, nevertheless I felt that I shared with the others in the class a sense of closeness to him. This was obviously due to the fact that the teachers I was training with had for appreciable lengths of time been in direct contact with Alexander since they had been participants in the teacher training course that Alexander had been running during the last twenty-four years of his life. So those teachers were now passing on to us the nourishment they had been absorbing from their contact with the source.

A special trait of Alexanders character was his negative stance to dogmatic beliefs. We read that he questioned every fixed belief that was conveyed to him as knowledge during his school years. Consequently, he unfailingly retained a non-dogmatic stance with reference to his own work as well. He is reputed to have said, Unless I am proven wrong I will carry on with the work as I do. In this sense, teaching the technique was for him a continuous process of re-assessment of its fundamental principles. I reckon that this attitude to teaching was more prevalent in the early days than it is now fifty years later. Perhaps this is because there was a fervour for the work then that made this continual reassessing more imperative. The work had to be asserted and protected from assaultsnote: F.M. wrote MSI (Mans Supreme Inheritance) to protect his technique against plagiarism and took legal action against a case of defamation (the South Africa Libel Action). This element of fervour for the work for its own sake was definitely traceable right down to the time of my training.

It is worth noting that F.M had singled out the antigravity movement from sitting to standing as his principal procedure for demonstrating the principle of the primary controlor as it is also called the head-neck-back relationship. Both in private teaching as well as in the set-up of his training course it remained the procedure through which basic experiences were conveyed to pupil or trainee and through which the pupils or trainees accumulated tightnesses and flaccidities could be reorganized into a balanced working as a whole. The supremacy of this procedure was equally indisputable during my training. In this connection, I remember, for instance, the enthusiasm of the teacher involved in the process of directing to get the primary control going while guiding the student from sitting to standing, and the exclamatory Thats it! to the student, when the intention was achieved. And good girl! if it was a female student who was the targetgood because she was not interfering, and naughty! if she did not inhibit. And there you go, was another one of those expressions. Parenthetically: a decade later, the focus of attention would be shifting from chair work to application workthe prime advocate of this being Marjorie Barstow in the USA. This was not the case at CTC or any other of the teacher training courses in London, but a broader movement in teaching the technique claiming to free the Alexander principles from the bonds of tradition in order to make them more adaptable to group teaching.

I would like to emphasize one more point regarding the focus of attention in those early days. It was simply to help the self progressively function in all action, conduct and thinking as a connected whole. That was the attitude permeating work in class. The interrelationship between the whole and its parts with respect to use and functioning was, broadly speaking, the theme around which training revolvedthe primary control being the mechanism through which the self (in the sense that Alexander used the term) could be helped to function as a concerted whole.

Consequently, the lesson passed on to us during my training was the inculcation of the primary control as a guiding principle in all activitynot only during class, but by and large in living. For this to happen, our teachers helped us, in the beginning through simple procedures and progressively through more complex ones, to grow a keen awareness of what the primary control involved so as to gradually develop the rudimentary skill of consciously integrating into its dynamics every intended actthis ability reaching a more advanced stage in the fully-fledged Alexander teacher. By the same token, the teaching skill that was required of us as graduates did not rest on sheer manipulative use of the hands, but on the hands becoming connected to our use as a whole, seeing that the experience of being a connected whole could not be conveyed in any genuine way to a pupil unless we as teachers knew how to generate and maintain it in ourselves from moment to moment. I make reference to the above training circumstances to show that emphasis on the whole was a priority issue in both training and teaching in the 1960s. A fleeting glance at the titles of literature on the technique since the time of Alexanders writings to our day can reveal where the weight of attention was placed in earlier days and how it has shifted over time.

In this connection, I remember reflecting on the comments made in class about Alexander having at the last minute withdrawn from a research project arranged by the American philosopher John Dewey [1] with funds that had been raised from a charitable organization. The impression conveyed was that F.M. was suspicious of research carried out by anyone with no background in the technique. On the other hand, he did not seem to oppose Frank Pierce Jones [2] attempts to set up pilot studies on aspects of the techniqueFranks first pilot study being in 1949, when F.M. was still alive.

With hindsight, I am inclined to think that F.M.s reservations might have been due to his protective attitude towards his technique and his conviction that his technique addressed the whole psychophysical selfas reflected in his writingswhereas research set-ups, by definition, concentrate on a particular part of the body, the objective being to investigate the effect of the technique on the function of that particular part. Thus, the original purport of his work that he so forcefully put forward during his lifetime might run the risk of treading in the background.