PONDS, LAGOONS, AND WETLANDS FOR WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT

PONDS, LAGOONS, AND WETLANDS FOR WASTEWATER MANAGEMENT

MATTHEW E. VERBYLA, P H D

Ponds, Lagoons, and Wetlands for Wastewater Management

Copyright Momentum Press, LLC, 2017.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations, not to exceed 250 words, without the prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 2017 by

Momentum Press, LLC

222 East 46th Street, New York, NY 10017

www.momentumpress.net

ISBN-13: 978-1-60650-701-8 (print)

ISBN-13: 978-1-60650-702-5 (e-book)

Momentum Press Environmental Engineering Collection

Collection ISSN: 2375-3625 (print)

Collection ISSN: 2375-3633 (electronic)

Cover and interior design by S4Carlisle Publishing Service Ltd.

Chennai, India

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A BSTRACT

Engineered ponds, lagoons, and wetlands have been used for centuries to treat and manage wastewater, and they are still widely used today. They require very few external energy and material inputs and provide ecosystem services for communities. This book presents a compilation of guidelines to design ponds, lagoons, and wetlands for the treatment and management of domestic or municipal wastewater, agricultural wastewater, and industrial waste. Sufficient detail and clarity is provided for practitioners to use this book as a reference, and for senior year or graduate college students to develop an understanding of the design concepts for these engineered natural treatment systems.

KEYWORDS

waste stabilization ponds; lagoons; constructed wetlands; wastewater treatment; sanitation; design; operation; maintenance; small flows; industrial wastewater, agricultural waste

C ONTENTS

I would like to acknowledge Stewart Oakley, whose short courses on waste stabilization pond design have inspired thousands of students and professionals throughout the world, including myself. I first took Dr. Oakleys short course in 2009 at the AIDIS conference in Guatemala City. I acknowledge my PhD advisor Jim Mihelcic, for giving me the opportunity to study waste stabilization ponds. I would also like to acknowledge Jerry Hopcroft and Premkumar Narayanan, for helping review and format the book. Finally, I would like to acknowledge Wendy Antunez for her help and support.

__________________________

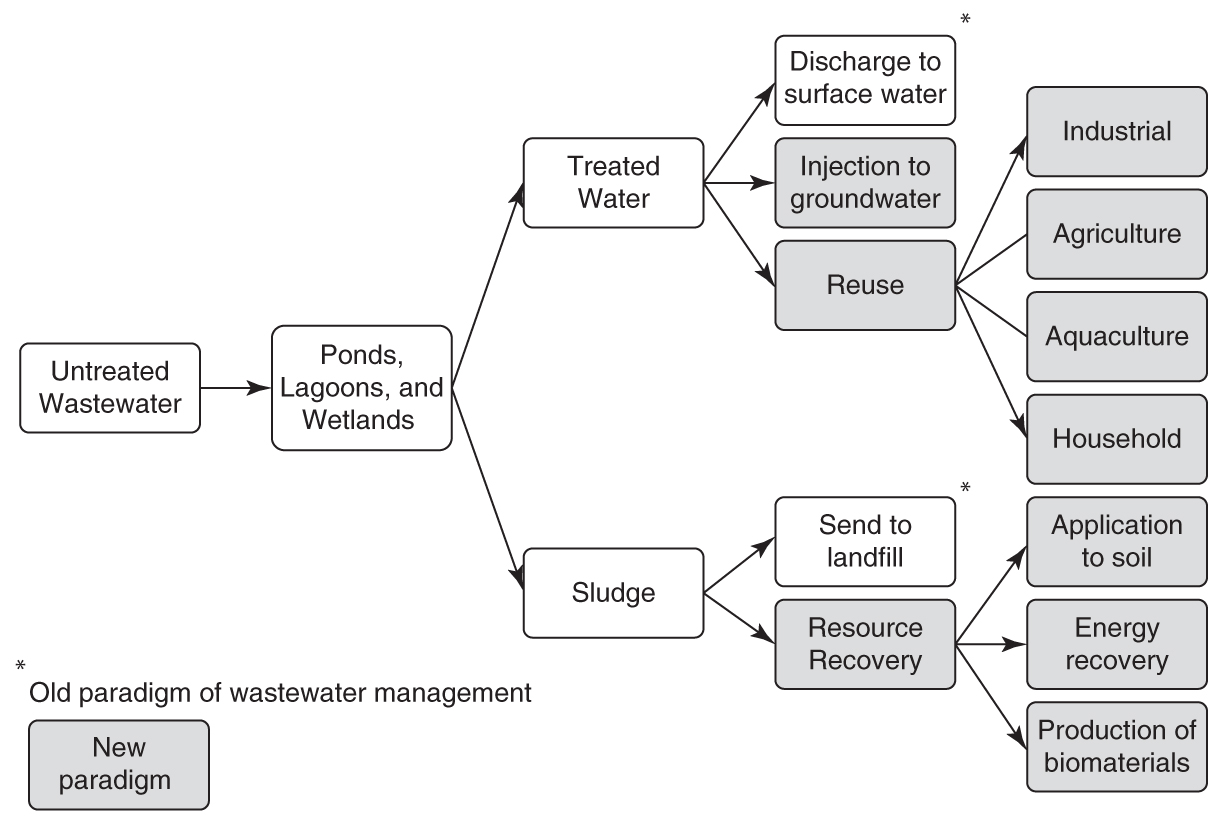

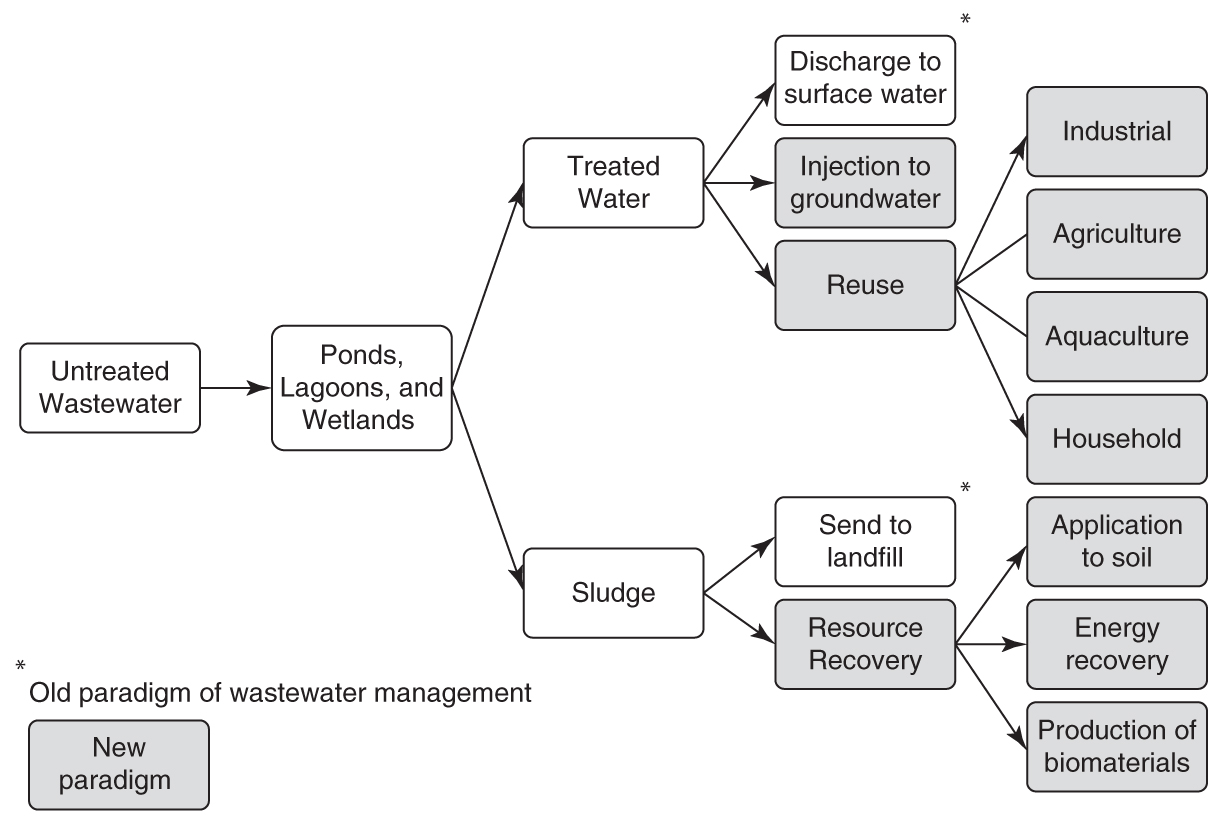

The paradigm for wastewater treatment is changing. Alterations in population and climate are causing freshwater to become increasingly scarce. The management of water resources does not occur in isolationthere are irrefutable linkages between water, energy, and nutrients in the environment. The ways water and nutrients are currently managed and the ways energy is currently produced are no longer sustainable. The new paradigm for the treatment of wastewater is to reclaim water, energy, and nutrients rather than remove them prior to discharging treated effluent to receiving waters (Guest et al., 2009). Engineered natural systems have been used for centuries to manage and treat wastewater throughout the world. In the aftermath of the industrial revolution, mechanized water-treatment technologies were developed. While many of these mechanized technologies are highly efficient, they often require high energy and material inputs. Natural systems require little to no external energy and material inputs. Mechanized wastewater treatment technologies are certainly appropriate in a variety of settings, including low-income, middle-income, and rural high-income regions. These systems are particularly well suited for locations where wastewater is reused in agriculture, making them particularly appropriate for the new paradigm of wastewater management with resource recovery priorities.

Treated wastewater may be discharged to receiving waters, injected into groundwater, applied to soil, or reused for a particular activity (e.g., aquaculture, industrial cooling). If treated water is discharged to receiving waters (rivers, streams, lakes, oceans, and aquifers), it must be treated to ).

Potential end uses for wastewater and associated sludge.

The use of natural wastewater treatment systems driven by sunlight, gravity, and natural biological processes is synergistic with sustainable development. These systems help offset the need for energy from fossil fuels, and they can also create habitats for wildlife and may play vital roles in amphibian conservation (especially if design is approached from an ecological perspective) (Shulse et al., 2010; Worrall et al., 1997). Natural wastewater treatment systems can become green spaces, which serve as community resources, promoting social and environmental benefits and improving the overall well-being of community members (Wright Wendel et al., 2011). Instead of simply discharging treated water into receiving waters, alternative uses of treated water (e.g., reuse or land application) should always be evaluated. Natural systems such as ponds, lagoons, and wetlands have been found to have more favorable environmental, social, and economical sustainability factors than mechanized technologies, especially for treatment plants receiving less than five million gallons per day (Muga and Mihelcic, 2008).

Natural wastewater treatment systems can become green spaces that serve as community resources, promoting social and environmental benefits and improving the overall well-being of community members.

Natural treatment systems are widely used in small cities and towns throughout the world. However, the needs of these communities are rapidly changing. The majority of population growth over the next few decades is expected to occur in smaller cities and towns with current populations of less than 100,000 (WaterAid/BPD, 2010). There is a need to ensure the appropriate design of wastewater systems to meet the changing needs of these populations. Relative to larger urban centers, small cities and towns often have plenty of available land, but limited resources, and as a result, they may have less ability to pay for the highly trained technical staff and external energy and material inputs needed to run mechanized wastewater treatment systems. Natural systems require larger areas of land than mechanized systems, but they require little to no external inputs of energy and materials, and they are inexpensive to run and require very little maintenance. Another economic advantage is that the purchase of land needed for these systems, while expensive, is a recoverable expense, unlike the purchase of electricity or material inputs.

Wastewater from households contains a variety of contaminants; the pollutants in wastewater are most commonly measured in terms of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), chemical oxygen demand (COD), total suspended solids (TSS), as well as nitrogen (total and ammonia) and phosphorus. Wastewater produced by households (domestic wastewater) comes from dishwashing, showering, laundering, and toilet flushing. Wastewater produced by industrial facilities can vary drastically in composition, depending on how the water is used and the type of industry. Industrial facilities may be required to provide some type of pretreatment prior to discharging wastewater to a municipal sewer system. Industrial wastewater can contain higher concentrations of contaminants such as salts, heavy metals, organic or inorganic chemicals, and emerging chemical or biological contaminants. Prior to designing a natural wastewater treatment system, it is essential to know the source of the wastewater and its composition, as this can greatly affect the design requirements. The wastewater flow rate per capita or per industrial facility can also vary from region to region and may be affected by the following factors: population density (more densely populated areas tend to use less water per capita); cultural norms and customs that affect water use in the household (e.g., in some countries, dishwater and shower water is not discharged to the sanitary sewer system); and characteristics of the sewer collection system (older systems typically have higher contributions from inflow and infiltration). For more information about typical wastewater characteristics and flow rates, the reader should consult existing textbooks (e.g., Metcalf and Eddy, 2003).