Copyright 2014 by Mark Nelson. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in reviews.

Published by Synergetic Press

1 Bluebird Court, Santa Fe, NM 87508

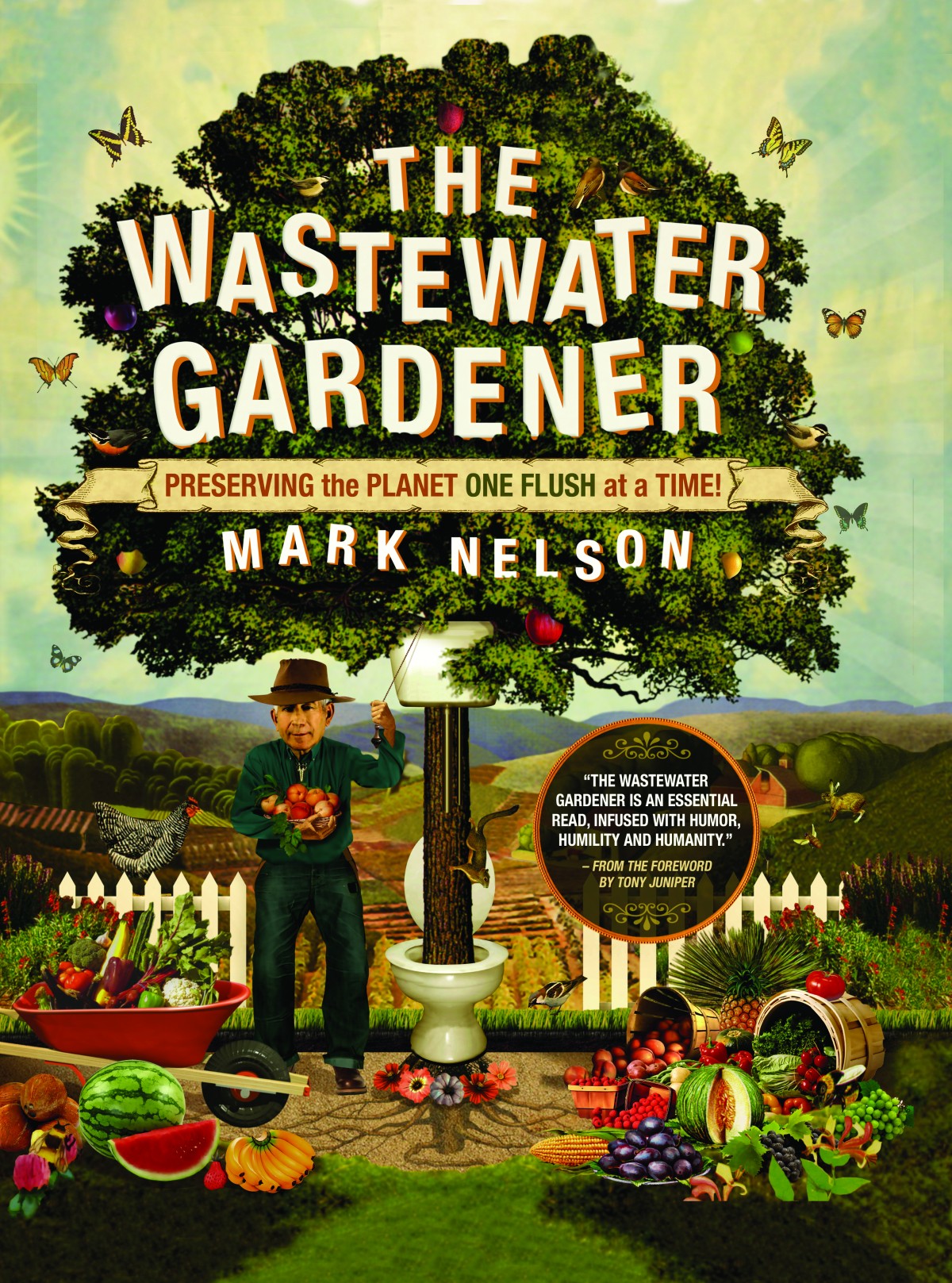

The Wastewater Gardener Mark Nelson, 2014

Foreword Tony Juniper, 2014

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nelson, Mark, 1947

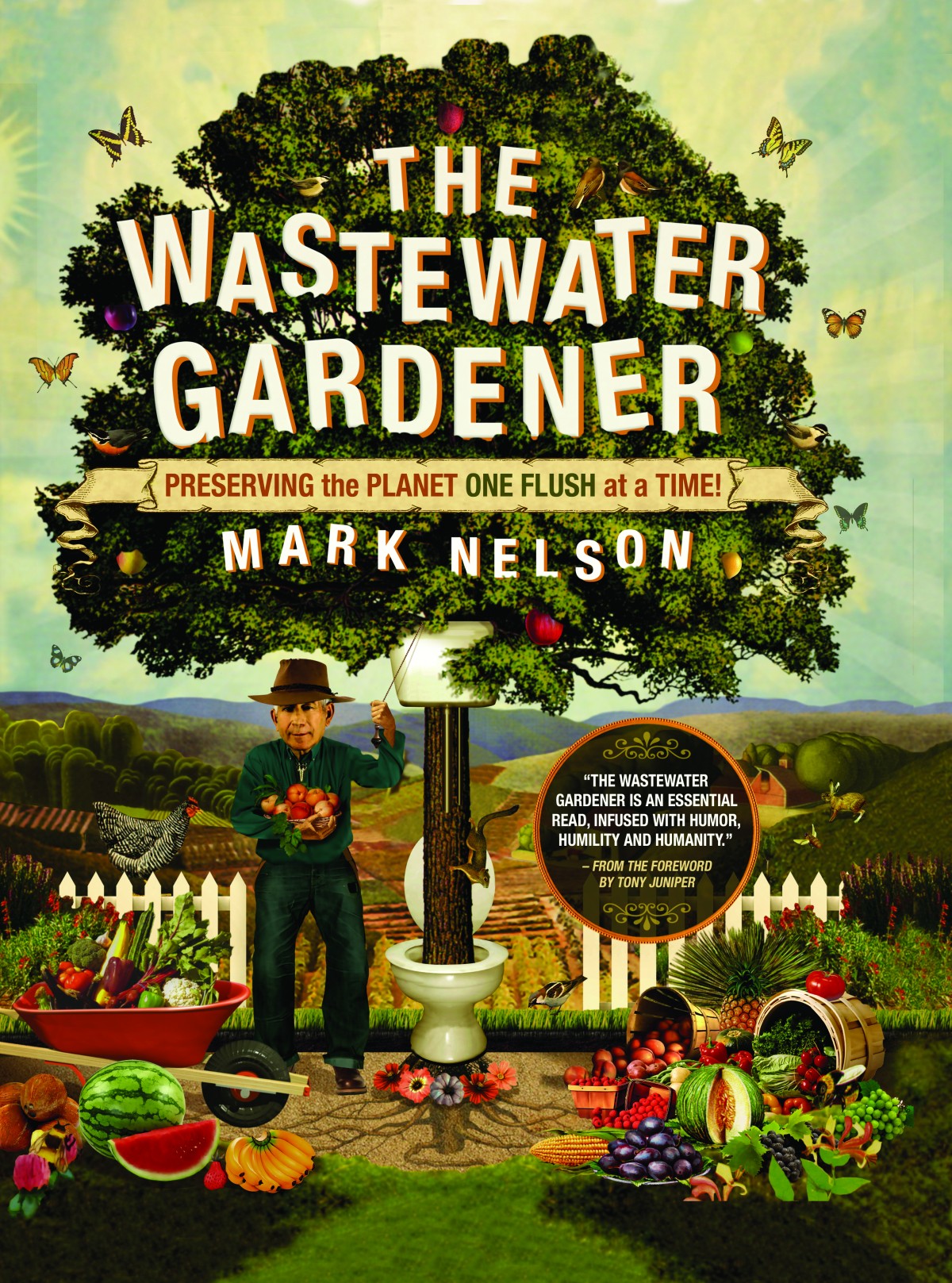

The wastewater gardener : preserving the planet one flush at a time! /

Mark Nelson ; foreword by Tony Juniper. -- First edition.

pages cm

Other title: Preserving the planet one flush at a time!

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-907791-52-2 (hardcover) -- ISBN 978-0-907791-51-5 (pbk.)

1. Sewage irrigation. 2. Water reuse. 3. Sewage--Environmental aspects.

4. Gardening--Environmental aspects. 5. Constructed wetlands. I. Title.

II. Title: Preserving the planet one flush at a time!

TD760.N35 2014 2014009840

628.168--dc23

Cover concept by David Rogers.

Cover art, illustrations and map by Jeff Drew

Cover photo of author by Stephen Muller

Book design by Ann Lowe

Editors: Linda Sperling with Hugh Elliot

This book is dedicated to Susannah Garrett, mi Fortuna,

who makes me appreciate my suerte every day.

Foreword

T HERE ARE SEVERAL MODERN SYMBOLS of ecological crisis. Gas-guzzling vehicles, airliners, coal-fired power stations and landfill sites are among them. While few people would add flush toilets to the list, there is increasingly good reason to see why that might be the case.

Freshwater is one of those day-to-day necessities that many of us have become used to taking utterly for granted. Delivered clean and safe through pipes to homes and offices, it can seem like an endless resource that will always be easily available. Reality is somewhat different, however, for in a planetary sense freshwater is not as abundant as it can sometimes seem to be, far from it in fact.

Of the 1.4 billion or so cubic kilometers of water that we have on Earth, nearly all of it is in the oceans and therefore salty. About 97.5 percent of it is in that form. Of the remaining 2.5 percent that is fresh, some 60 percent is trapped in ice caps and glaciers with 30 percent more in groundwater, and therefore for the most part not immediately available to us for farming, domestic supply and industry. The tiny remaining amount that is generally renewable and in rivers, lakes, ponds and clouds, is subject to increasing demand from more people living in larger, growing and ever more demanding economies. Not only is that little slither of freshwater under mounting pressure, its local availability is also subject to growing volatility because of changes taking place in the Earths climate.

We go to great lengths to ensure that societies have enough freshwater, and each year spend billions of dollars on extracting it from the environment, putting it in reservoirs, cleaning it and then piping it to where its needed. The precious resource to which we go to such lengths to supply is every day then turned into wastewater of different kinds, including by the simple act of flushing lavatories.

This convenience was of course invented for good reason and the sanitary engineers who during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries contributed to the rise of the modern toilet can correctly be seen as among those who helped build the healthy lifestyles so many of us enjoy today. They helped to reduce the spread of infectious disease and brought to the mainstream devices that would increase peoples lifespans.

At the same time though, they introduced technologies that would require some ten thousand tons of water to remove and treat each ton of human excrement and lead each one of us with a flushing toilet to use in the order of ten thousand gallons of water a year to send our waste away.

Increasingly though, we are finding that in our shrinking world there is no away. In the end all of our waste ends up somewhere, often contributing to different environmental problems when it arrives at its final destination. Considering the dual trends of rising demand for freshwater and the increasing amount of nutrients leaving our toilets building up in the environment, those problems will only become more complex. Fortunately though there are solutions, and in this marvelous book Mark Nelson shares his decades long experience to explain what they are.

His basic conclusion is that by copying nature, and in particular how wetlands work, cost effective, healthy and sustainable alternatives to our wasteful sanitation systems can be put in place, not only defending us from the effects of water scarcity, but also protecting ecosystems from impacts that can be caused by too much of our bodily wastes being released into them. He takes readers on an inspiring journey, one that is rendered all the more impactful by his stories of doing it for real.

From Mexico to Western Australia and from Bali to Arizona, Nelson has designed and installed systems that have provided local sanitation solutions while bringing global benefit and his stories show how hes done it with humor, humility and humanity.

Painting a picture of how soils, plants and water might be harnessed in ways that meet our needs without pipes, sewage works and pollution, Nelson inspires us to see opportunities that are not only practical, but if designed well also beautiful. Channels of water flowing between willows, water hyacinths, lilies, rushes and cattails, with the cleaning function of roots and microbes harnessed in the purification of water, could almost not be more different from high-tech centralized wastewater treatment facilities.

The construction of beauty is, however, a very practical response and one predicated on the understanding that the excrement we do so much to get rid of is essential to life. All living things require nutrients to exist, grow and reproduce and the material we eject from our bodies and into sewers is a massive source of those life-giving materials. That we have lost sight of this basic reality and strive so hard to place ourselves outside nature is one further manifestation of the industrialized mindset that any rational reading of our direction of travel would suggest we need to change.

In common with others who present the kinds of durable solutions that are needed to deal with the multiple challenges that confront us, Nelson describes how it is not only different treatment systems that are required, but also a shift in this unrealistic mindset. Especially through how we might see things differently by taking more of a system-based approach, compared with more reductionist ways of thinking that seek to deal with each problem at a time and in isolation from related ones.

Perhaps through the pages of this important book the flush toilet might one day become not only a symbol of unsustainable development, but also of the hazard that can accompany solutions that meet one challenge while not considering others. For while the flush toilet has been successful in protecting public health, it will, because of, among other things, progressive water scarcity, nutrient depletion and environmental impact, not be a solution that can lend itself to upwards of nine billion people.

This is why The Wastewater Gardener is an essential read for anyone with an interest in sustainable development, water, urbanization, sanitation and public health. For while it might seem that the only alternative to the open sewers that characterized so much of our past, and in too many places the present, is the installation of flushing toilets and building sewage works, there is in many cases a better way, one that brings not only health and sustainability, but also beauty. Infusing it all is the realization that nature does not do waste, and if we wish to endure, then neither should we.

Next page