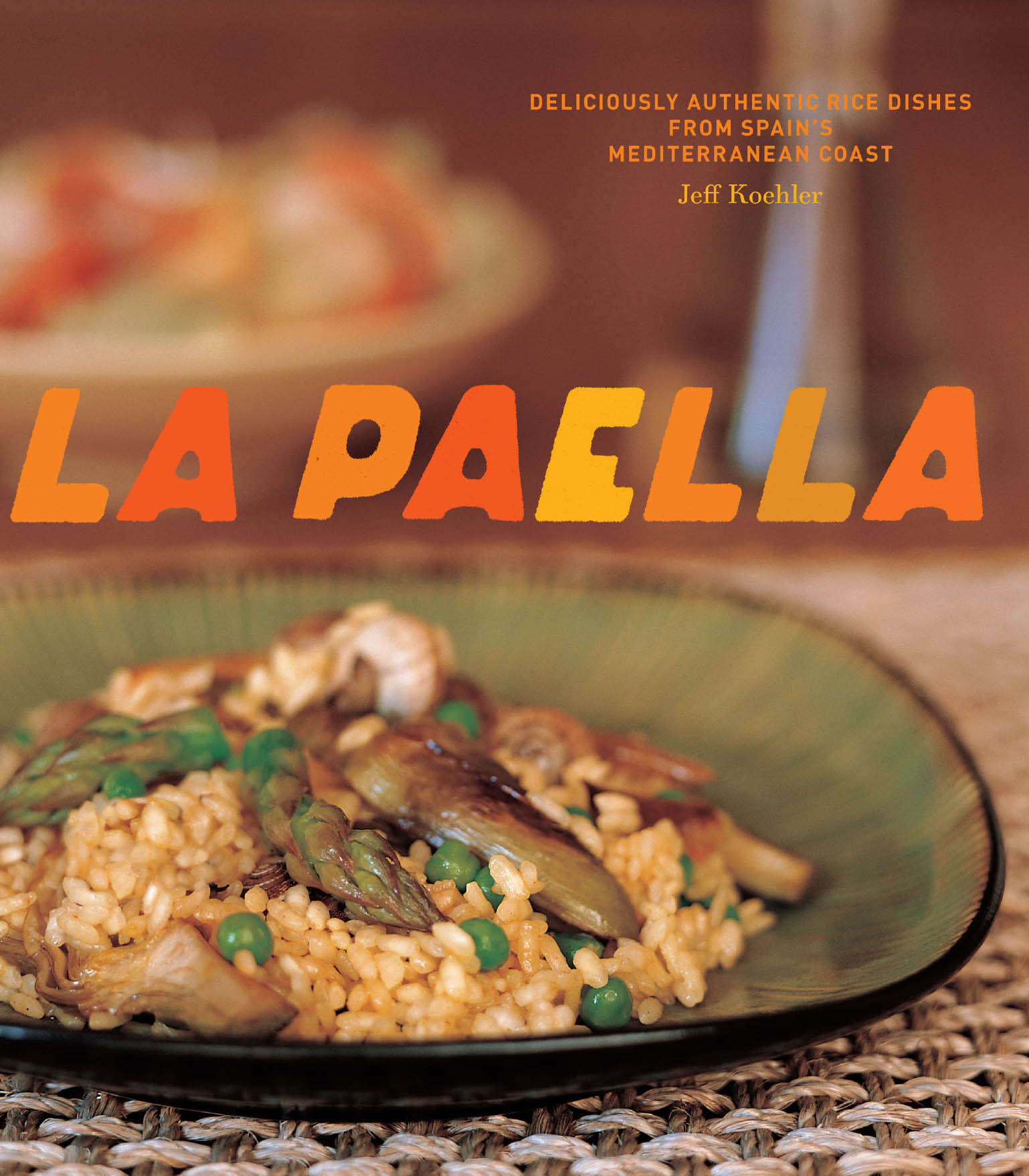

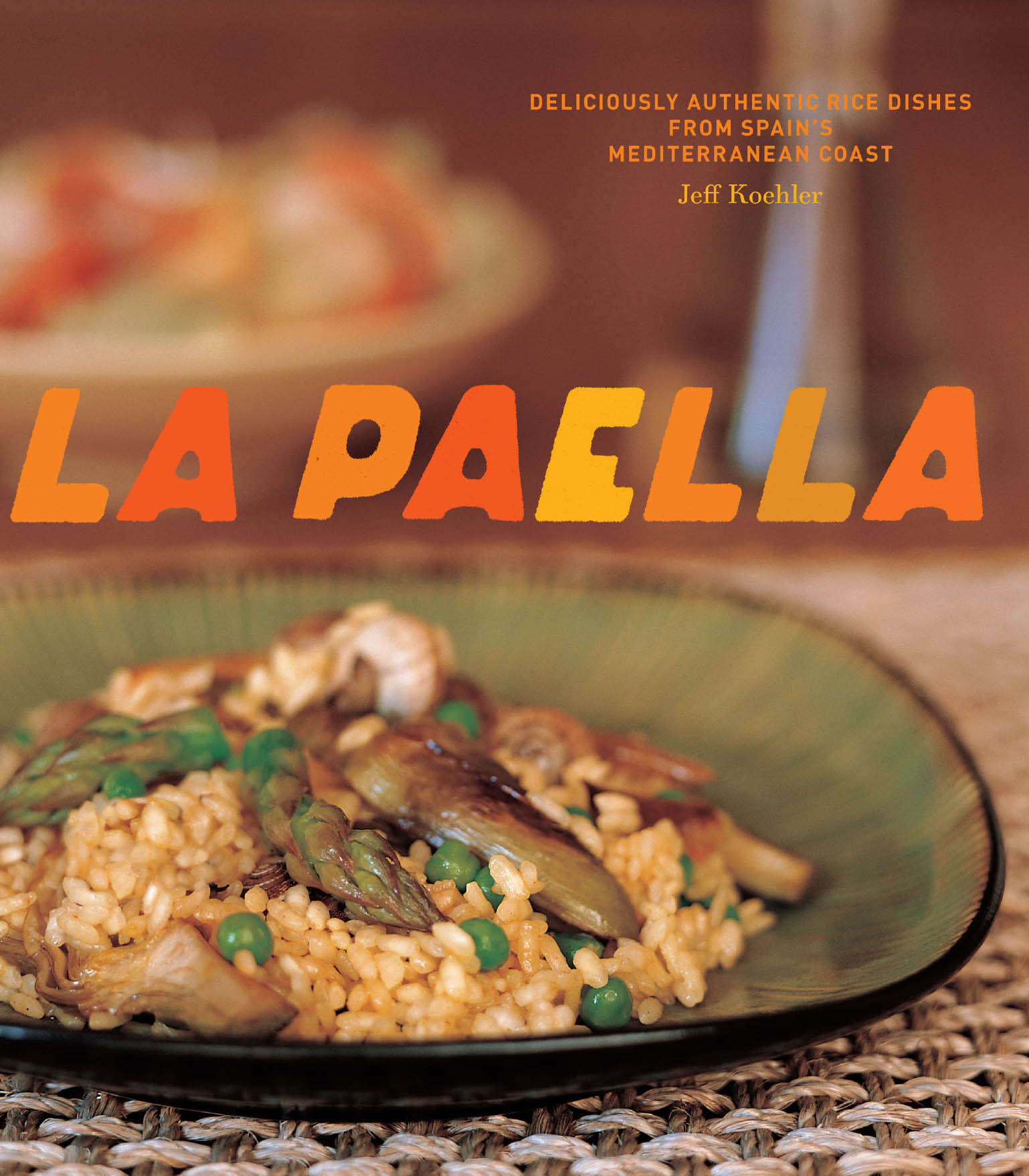

Text and photographs copyright 2006 by Jeff Koehler.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

isbn : 978-1-4521-5960-7 (epub)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

isbn : 978-0-8118-5251-7 (hc)

Designed and typeset by Benjamin Shaykin

Typeset in stf Walbaum, ptf Bryant, and ff DIN

Chronicle Books llc

85 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94105

www.chroniclebooks.com

a lEva

Contents

Introduction

Paella is Spains most famous and cherished dish. Its full of ritual and myth, tricks and techniques, and strict rules (Never stir the rice! Never cover while cooking!), yet open to interpretation and argument about what it can or cant include. Paella is often at the center of family gatherings and village or even city fests, especially in Valencia and Catalunya, along Spains Mediterranean coast. There are other traditional ways of cooking rice in Spain, but paella is the most dramatic. You may prefer a moist rice dish of rabbit and quail in the cazuela (casserole) or a soupy rice cooked with lobster in a pot-bellied caldero, but nothing is as impressive as a large paella. Tip a thin, eighteen-inch-wide pan of rice the color of antique gold, studded with black mussels, toward a hungry table and there will be oohs and aahs. Among rice dishes, paella is king. Its spectacular, memorable, and deliciousdevastatingly so when done well.

I vividly remember my first paella. A decade ago I followed a Catalan woman named Eva home to Barcelona from graduate school in London. A few days after arriving, I found myself sitting around the table at her parents house for the weekly family paella. Her mother, Rosa, was born in Barcelona, though Rosas parents both came from a tiny village in the Valencian countryside. Rosas mother died when Rosa was very young, and Rosa spent part of her childhood among aunts (on both sides) in the village while her father worked in his small Barcelona grocery store. The aunts battled for the girls attentionand comforted herwith their paellas. For more than forty years now, Rosa has been making near-weekly paellas for her family. There is an open invitationjust call by Friday evening so that enough shellfish can be bought in the market Saturday morning. Cuantos mas seremos, mas reiremos, goes Spanish thinking. The more we will be, the more we will laugh. And the more we will be, the bigger the paella!

On that memorable afternoon, Rosa carried her signature shellfish paella into the dining room, and when she tipped it toward us, I burst into applause, which drew more attention than the gorgeous, baroque rice. Plates were passed down and heaped with rice, jumbo shrimp and sweet prawns called cigalas, soft strips of cuttlefish, and tiny clams with grains of rice nestled inside. The thin layer of slightly caramelized rice known as socarrat was scraped from the pan and divided. It all tasted even more sublime than it looked. The nuttiness of the cuttlefish mingled with the sofrito (a slow-cooked aromatic tomato base), and the seafood was fragrant with sweet, smoky pimentn (paprika) and saffron. It was, quite simply, perfection. My affair with paella had begun. And so did my life in Spain: I stayed and married Eva not long afterward.

The Spanish word for rice, arroz, and the Catalan and Valencian arrs are derived from the Arabic ar-ruzz. The Arabs introduced rice into Spain in the eighth century, at the beginning of their long rule on the Iberian peninsula. They planted it around Valencia, including the marshy edges of the Albufera, the freshwater lake on the south side of the city, slightly inland from the sea (the name comes from the Arabic for lake, al-buhaira). When Jaume I entered the city in 1238halfway through the 700-year-long Christian reconquista of the countryhe found rice fields abutting the city. Cultivation has continued there, focused around the Albufera. Today the rice fields along the silted-up edges of the lake are cut with eel-rich canals and produce the finest and most sought-after Spanish rice.

Vast irrigated orchards and verdant produce gardens, the huertas that Valencia is famous for, begin at the edges of the rice fields and radiate across the region. It was here in these huertas that paella was born. Rice was a basic staple and field workers prepared it with their garden vegetablessuch as fresh beans, tomatoes, and artichokesand the snails they found among the rosemary and thyme that grew wild. On lucky days, they added a freshly killed rabbit or duck, and on special occasions, they slaughtered a chicken. The rice dish, cooked in a wide, shallow pan over the embers of olive- or orange-tree branches, was called arroz a la valenciana. At the end of the nineteenth century, it was finally named paella valenciana, after the distinctive pan the rice was cooked in and the place from where it came.

Variations came later, drawn from available ingredients. There may be only one Valencian Paella . Paella adapts well to a variety of seasonal ingredients, from fresh game in autumn to asparagus in spring. You can be creative. Why not add squid, sardines, rosemary, or wild mushrooms?

But what makes a paella authentic? I have heard an extreme few claim that a paella wasnt a true paella unless it was made with lime-rich water from Valencia. Others say that anything other than paella valenciana is simply un arroz en una paella (a rice in a paella pan). The first claim is far too narrow, and the second is just playing with words. A paella is a paella as long as a handful of key requirements are met. First, highly absorbent short- or medium-grain rice is at the center of the dish. A paella is a rice dish first and foremost, and the purpose of each cooking step and every ingredient is to flavor it. Second, it includes olive oil, has a sofrito base, and is tinted yellow with saffron. Third, and most important, it is cooked in a wide, flat paella pan. Apart from giving the rice its name, the pans shape allows the rice to be cooked in a thin layer. This puts as much rice as possible in contact with the bottom of the pan, where the flavors lie, and also allows the rice to cook evenly, with the quick evaporation needed to obtain the paellas dry texture and separate, firm grains.

The basic technique for preparing a paella is fairly straightforward, allowing, of course, for personal preferences. One standard method goes like this: The chicken, rabbit, game, poultry, and/or seafood are browned in olive oil. Then the vegetablesgreen bell peppers, red bell peppers, green beans, artichokes perhaps, tomatoes for certainare added and slowly cooked down into a pulpy sofrito. Sweet pimentn

Next page