To my family and extended family, near and far, especially the young onesMai, Masa, Mako, Miki, Hayato, Sofia, and Paolo.

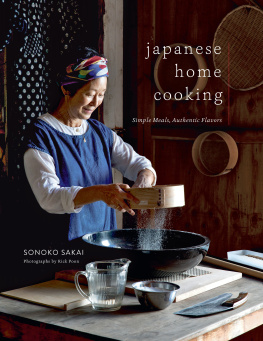

Text copyright 2016 by SONOKO SAKAI.

Photographs copyright 2016 by MATT ARMENDARIZ.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4521-4875-5 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available.

ISBN 978-1-4521-4287-6 (hc)

Designed by VANESSA DINA

Food styling by SONOKO SAKAI

Typesetting by FRANK BRAYTON

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

WWW.CHRONICLEBOOKS.COM

CHAPTER ONE:

Onigiri Fundamentals

and Master Recipes

INTRODUCTION: RICE RITUALS

Every onigiri has a story. My story takes me back to the 1960s, when I was growing up in Kamakura in Kanagawa Prefecture, not far from Tokyo. Down the street from where we lived, a small family owned a rice mill, where the townspeople bought freshly milled rice. The pleasant nutty aroma of the rice bran always permeated the shop. One of the old millers morning rituals was to write a haiku on the blackboard that hung outside his business, such as this famous one by Basho:

Old pond

Frog jumped in

Sound of water

The seasonal verses entertained the passersby, including the tourists who came to visit Daibutsu, the Big Buddha of Kamakura. Sometimes the miller wrote childrens verses for us to sing out loud. My mother always praised his calligraphy, and on occasion she asked him to write letters for her.

In the late spring, as I rode the train to school, I could glimpse the farmers in the rice paddies, planting seedlings by hand. When the days got warmer, the rice stalks grew and turned into a lush green carpet, thriving with lifetadpoles, nymphs, dojo loach, and water striders. The most exciting time was during the fall harvest, when the farmers cut the golden rice stalks and hung them on wooden racks to dry in the sun. Their work never seemed to end.

The wife of one of the farmers visited our house regularly, carrying a huge bamboo basketa portable vegetable shopon her back. Daikon radishes, kabocha squash, eggplants, cucumbers, and delicate offerings of fermented soybeans wrapped in rice husks and farm eggs wrapped in old newspapers. Whatever she pulled out of that basket amazed us kids. Her basket became particularly heavy after the rice harvest, because she was carrying new crop rice. New crop rice tastes delicious, because its so fresh. Though I was not a child of a rice miller or a rice farmer, one of the Japanese rituals of growing up was to pray for a good rice harvest. I still do.

My favorite way to eat rice is to make onigiri. My grandmothers onigiri were divine. She made rice in a small cast-iron pot on the wood-burning stove in the living room. She lived next door to us, so I would visit her every day, and she would often treat me to onigiri. I enjoyed the time we passed together while we waited for the rice to cook. She told me stories of her girlhood, of her favorite scenes in The Merchant of Venice and Romeo and Juliet, of the Chaliapin steaknamed for the famous Russian opera singer who visited Japan in 1908her parents had treated her to when she was a young girl. Japanese people hardly ate beef back then, so eating that piece of meat was a cultural awakening for my grandmother.

When the rice was cooked and we opened the lid, the steam would rise and fog up my grandmothers glasses. Seconds later, a grassy aroma would fill the room. Grandmother would give the rice a quick turn with her wooden rice paddle and make the onigiri while the rice was still warm. Her onigiri were filled with okaka (hand-shaved bonito flakes seasoned with a few drops of soy sauce) and wrapped in crispy nori (dried seaweed). We would sit on the sunny porch with a view of her garden, eating the onigiri. The first bite smelled of Kamakuras salty sea breeze. The second bite was full of the taste of the delicately sweet and tender rice, and the third bite of the smoky okaka. I never wanted these delicious times to end.

It is now my turn to share my love for rice and onigiri with you. For most of my adult life, I have made Los Angeles my home with my husband, Katsunisa, and our son, Sakae. During the summer holidays, Tyler, my stepson, came to visit us from London. I was always busy feeding the boys. Crispy grilled onigiri was their favorite food on the BBQ. Since the 1980s, I have been teaching Japanese cooking classes and writing about food. My first cookbook, The Poetical Pursuit of Food: Japanese Recipes for American Cooks, was a collection of stories and recipes about the days spent in the kitchens of my mother and grandmother, as well as my own in California. My cooking philosophy has remained the same: freshness, beauty, simplicity, health, and fun are what matter most to me in the kitchen.

In 2011, I started a project called Common Grains, dedicated to sharing the Japanese tradition and pleasures of eating grains and vegetables as part of a healthy lifestyle. I have gone back to Japan every year to visit and learn from farmers and artisans, sake brewers, katsuobushi makers, and miso makers, and to study noodle making by hand. With a generous seed grant from Glenn Roberts of Anson Mills, I have also been working with Southern California farmers, bakers, chefs, and cooks to restore the Southern California grain hub that existed until the beginning of the twentieth century. Our goal is to reestablish such heirloom wheats as Sonora White, emmer, and Red Fife, and other grains like barley, buckwheat, rye, and oats, and to advocate for sustainable agriculture and the value of food grown close to home.

Rice has been particularly important to me, as it forms the foundation of my Japanese heritage. With my collaborators, I have made thousands of onigiri at pop-up dinners, contests, food trucks, and workshops in California, Washington, Hawaii, and Hong Kong. I hosted the Rice Fest in Honolulu, where our onigiri contestants made the biggest Spam musubi in the world!

I am inspired by the outpouring of love for onigiri I encounter everywhere. The onigiri gatherings bring together formalists, who lean toward traditional Japanese shapes and fillings, and freestylers, who throw tradition out the door. No matter which camp people belong to, onigiri promote community and appreciation for food made by hand.

This book is a blend of tradition and originality. You will find classic onigiri (plain rice, a filling, and a dab of sea salt, wrapped in a piece of crispy nori) and creative onigiri (of the sort that shine at my pop-ups and workshops). My hope is to share a little taste of Japan and of my cooking philosophy, and a lot of flavor and fun with you. I hope to hear your onigiri story in person someday.

Next page