Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Roost Books

An imprint of Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

roostbooks.com

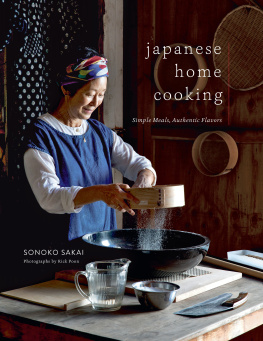

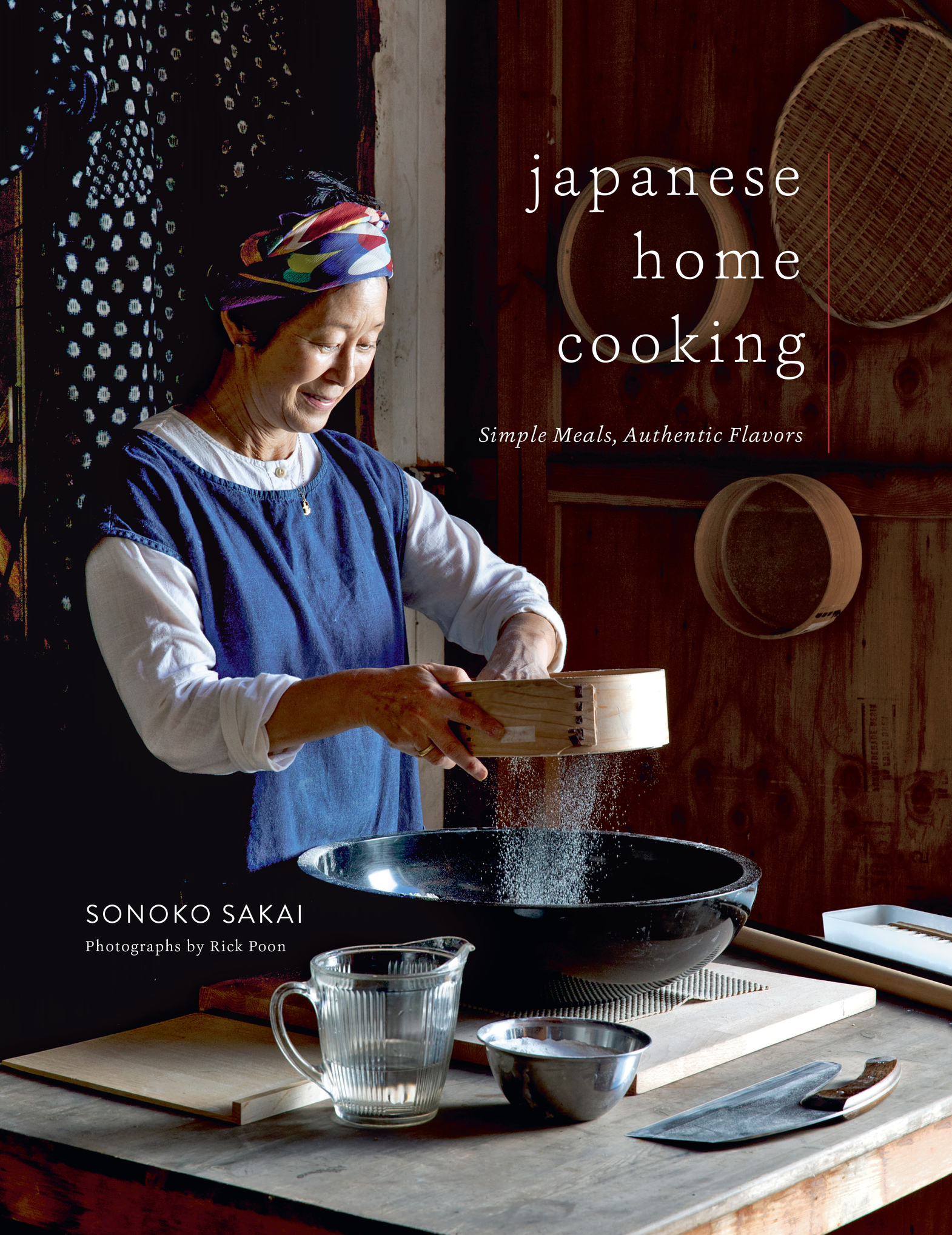

2019 by Sonoko Sakai

Photographs 2019 by Rick Poon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Roost Books is distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House, Inc., and its subsidiaries.

Book design by Laura Shaw Design, adapted for ebook

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Sakai, Sonoko, 1955 author.

Title: Japanese home cooking: simple meals, authentic flavors / Sonoko Sakai; photographs by Rick Poon; illustrations by Juliette Bellocq.

Description: First edition. | Boulder: Roost Books, 2019. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018041562 | ISBN 9781611806168 (hardback: alk. paper)

eISBN 9780834842489

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, Japanese. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX724.5.J3 S24 2019 | DDC 641.5952dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018041562

v5.4

a

contents

for my students

The artist Seiho Takeuchi (18641942) once told his students that they should first learn to draw from life as carefully as possible, then do so using their brush as little as possible; and that after that it was all satori, enlightenment. Cooking is the same: enlightenment.

KITAOJI ROSANJIN, artist and epicure (18831959)

introduction

In ancient Japan, a small mound of salt was served at each table setting so diners could salt their own food. This notion of salting your own foodteshio ni kakeruhas evolved over time to mean the act of nurturing, whether it is raising your child, making your own miso, or, as it applies to this book, cooking for the people you love.

This book is about Japanese cooking. It is also about home cooking. I was lucky to be raised with both. I was born in New York to Japanese parents and spent my childhood in Tokyo, San Francisco, Mexico City, Kamakura, and Los Angeles. While growing up, I had two wonderful teachers: my mother, Akiko Kondo, and my maternal grandmother, Hatsuko Ishikawa.

I watched my mother maintain a Japanese kitchen everywhere our family lived, which was often a challenge. She was an ingenious and resourceful cook who managed to make Japanese meals without always having access to Japanese ingredients. From my mother I inherited the arts of adaptability and flexibility. Shortly before I finished writing this book, my mother died at the age of eighty-nine. I was fortunate to have visited her in Tokyo just a few weeks before her passing. There is an old Japanese saying that when you really want to care for your parents, they are gone. So, care for your parents. My grandmother, who lived to the ripe old age of 102, was a modan (modern and open) person. She had a weekly regimen of baking bread, making pickles, practicing the tea ceremony, and going to church. Her baking ritual brought out the Westerner in her. She was one of the few people in Kamakura to own an oven, and she was still baking when she turned one hundred.

Her grandfather, or my great-great-grandfather, was Hermann Siber, a Swiss silk merchant who came to Yokohama in the 1870s looking for silk just after Japan opened its ports to the world. There he met Oshio, an accomplished geisha from Yoshiwara, the old geisha quarters in Edo (which is now Tokyo). My great-grandfather, Jiro Nakamura, was their mixed-blood illegitimate offspring, but that fact was shrouded in family secrecy. It was not until my grandmother was twenty years old that she learned of her ancestry after receiving a missive from Switzerland announcing Hermanns death. She learned that Oshio was not just a close family friend, as she had been told, but actually her grandmother. In my own relationship with my cherished grandmother, she related stories to explain what it meant to straddle two cultures.

As such, it is my hope that this cookbook reflects the values and practices of my mother and grandmother, as well as those skills I have developed in my own kitchen, an amalgam of todays contemporary cross-cultural experiences.

My father used to say that if you have a bottle of soy sauce, you can make Japanese food. He worked as an airline executive, and as one of the new generation of Japanese to live and work abroad after World War II, he was transferred from Tokyo to New York in the early 1950s. My mother joined my father in New York a year later, with my brother Hiroshi in her arms. In her new kitchen in their tenement apartment in Queens, she took in with amused curiosity the world of midcentury American cooking. She found dozens of empty TV dinner trays stacked on top of the refrigerator (my father felt there had to be a use for the aluminum) and a bottle of soy sauce in the otherwise empty pantry. Not surprisingly, Japanese ingredients were not readily available back then, but my father was able to find soy sauce in New York City. In those postwar years in the United States, soy sauce gave my father some comfort, even though it was sprinkled on TV dinners.

Artisans making soy sauce in Noda, Chiba Prefecture. (Hiroshige III, Meiji Period)

I am my parents first American-born child. At the time of my birth, anti-Japanese sentiments were still lingering in the United States. When my brother and I cried, the neighbor below us would hit the ceiling of his apartment with a broom and shout, Remember Pearl Harbor! My mother would take us out into the freezing cold New York winter to calm our nervesand hers too. Soon we acclimated to our new life in the United States and our time here got better.

In my baby book, my mother pasted a letter from my grandmother that honored my birth and detailed the contents of the care package shipped to New York: tea, miso, wakame, and kombuthe staples necessary for a Japanese pantry. I developed a sense of Japan through the fragrance of the Japanese food sent in these care packages. My mother learned how to combine American and Japanese ingredients and turn them into hybrid dishes. She made fried rice with chopped onions and Birds Eye frozen peas and carrots. She stir-fried the vegetables in butter and garnished the dish with crispy flaked nori. (Being able to use butter was a dream come true for someone who had survived wartime hunger.) Mother whipped up the fried rice so quickly that my teeth would tingle from the still-frozen vegetables.