Table of Contents

Thanks & Acknowledgments

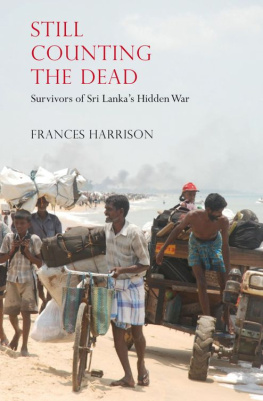

This book was about seven years in the making, and during that time I interviewed many of the major actors in the Tamil-Sinhalese conflict in Sri Lanka, India, Canada, and the United States. But many people who are not visible in the manuscript also made the book possible and guided me through some dangerous waters. There are some people I can no longer thank, as many of them, including Shankar Rajee, are now dead. I would, however, like to send undying thanks to both the living and the dead, including Bandula Jayasekara, David W. Lewis, Anita Pratap, Y.K. and Pushpa DeSilva, Dayan Master (whose lessons echo from cover to cover), the Goviyapana Boyz (especially Prabath, Krishan, and their families), Enno, Mercedes, Naranj Wijeera, Lucas Path, Mr. W. Edwin of the Aluvihara Buddhist Library, and many, many others.

Anne Horowitz, supereditor, put in big energies and tiny attentions to make this thing legible and real. Input and realism were also added with the help of Andrea Matson-DeKay (and the rest of the 4-PACK crew), E.W. (don Eduardo) Kutner, Angela Klaassen, Heather Noone, Brian (Kogen) Lesage, and my wife, Amlie, who not only fielded the idea in the first place but saw it all the way through until the final draft of the manuscript.

Thanks most of all to each of the patient individuals who were interviewed. Heres hoping Ive relayed your stories with the same precision and at least a portion of the passion with which you generously offered them.

This book is dedicated to anyone who has reasoned along enemy lines.

Chapter One:

COMPROMISES

We took some tea as a symbol, as a gesture, to the Palestinian people, picked by the Tamil people, as if to say, This is our sweat and blood, this is the only thing we have to give.

Shankar Rajee

The Day That Started with a Bang

The hand that set the 1984 bombs, Colombo, Sri Lanka

It was 5:01 AM, October 22, 1984. It could have been a morning two thousand years ago. Sri Lankas capital city, Colombo, slept under the pink clouds of dawn, palm fronds nodded in the tropical breeze, large-billed birds summoned up the sun, and the 5:00 AM train blew its whistle. In the street below, a couple of three-wheeled tuk-tuks sat, their engines puttering: taxi drivers waiting to take children to school or businessmen to their desks. One of these drivers leaned forward to turn on his radio, and his tuk-tuk was thrown backward in a spray of dust and debris, as if by a silent hurricane. The corner of the church across the street rose several meters from the ground. It sagged back down, crushing a Tamil man underneath, and then it rained cement shards and pieces of glass for a full minute afterward as people scrambled awake.

The explosion was heard over ten kilometers away. Since the country was in the teeth of a civil war, this wasnt as much of a surprise as if it had happened in, say, Oklahoma City, but, just to be safe, security forces, medical personnel, and a bomb squad were deployed, quickly scurrying to the address that was broadcast on the radios. They expected that the mop-up would be quick and minimal. Multiple ambulances were calledagain, just to be safe. The Sri Lankan army was put on alert. More than a few people assumed that the explosion was caused by a gas line that had caught fire, or that maybe the church had collapsed just because it was so old.

These teams pulled up to the front of the smoldering church at the moment that another bomb, at the south end of town, ripped open a bus station. Phone lines started to jam up, police and security forces were told to station themselves at the edges of town, and the Sri Lankan army picked up its weapons and headed over to the bus station, since these events were turning the dawn quite dark.

Five minutes passed. As this second emergency team arrived at the second scene, a third bomb, this one at the west end of town, detonated at a television transmission station owned by the state-run Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation, dropping the tower into a smoking mess of steel shavings. Five minutes later, an office building downtown erupted in a spray of concrete, spitting pebbles, rebar, plaster, carpet, and a few twirling chairs into the sky. Then, as if inhaled back into the building, the material returned to earth, floor after floor collapsing under its weight, instantly burying four people.

In a suburb, two people, clueless as to what was happening in the city at that minute, opened a box they found on the sidewalk. An enormous smoking mouth opened in the middle of the road, and their limbs were launched more than ten meters away. About two minutes later, at Fort Railway Station, an unexploded bomb was found by the police. While the Sri Lankan army was busy defusing that one, a second detonated nearby, flicking a train car that had just blown its whistle onto its side like a matchbox.

Six minutes of peace followed. Just as the police dispatch began to breathe a sigh of relief, someone called in to report a blast near the foreign ministry office.

There were no more emergency workers available, and the Sri Lanka Broadcast Corporation, from what remained of the broadcast tower, pleaded that people stay indoors, remain calm, and wait for authorities to unwire a city that had been turned into a distributed detonation device.

But it wasnt over. Five more explosions were yet to come in the next ninety minutes. And since that morning in 1984, more than a hundred thousand people have died early deaths in Sri Lanka as a result of civil war, terrorism, and political unrest.

The attack was organized by a man named Shankar Rajee, who, over afternoon tea, told me why he had done this. He said his intent was to cause terror. He said,

We realized that we needed to make the ruling class and the bureaucrats feel the pressure and tension of the war. We needed to make them listen to our grievances. With this in mind, we drew up an action plan... These would be symbolic explosions that would be designed to create enough panic, and, well, terror... to make the government realize that they were not as powerful as they thought.

Rajee brewed many dangerous ideas in the course of his life, and he spread the danger generously. An exporter of the concept of suicide bombing to the Middle East and one of the founders of the Sri Lankan Tamil militant movement, he fueled enough terror on that October morning to draw the attention that the Tamil cause needed. He felt justified. He had grown up under the heavy weight of riots, lynchings, arson, refugee camps, and an intimate education on the finer points of segregation. Raised in the war zones of Sri Lanka, and finding himself muzzled because of his ethnicity, hed had enough. So in his early twenties he moved to London. While there he met Palestinian militants, traveled with them to Beirut for training, pulled a trigger on the front lines, and explained the basics of suicide terrorism to the Fatah party. He left with a souvenir given to him by the PLO: enough ammunition to start a small war. Which he did promptly, as soon as he arrived back home.

The decade leading up to this bombing had been a politically charged competition of physical force between the Tamil minority and the Sinhalese majority (both of whom have been living on the island of Sri Lanka, formerly Ceylon, for as long as either group can remember). Up until Rajee bombed Colombo, the civil war had grown gradually from attacks by petty criminals to deadly discharges launched by organized groups. Murders committed out in the farms triggered riots in the towns, which in turn provoked multiple murders in temples, which then set off massive riots in the cities. With each blow, the government grew more hardened and conservativeand this in turn led to more hardened and conservative militant groups.