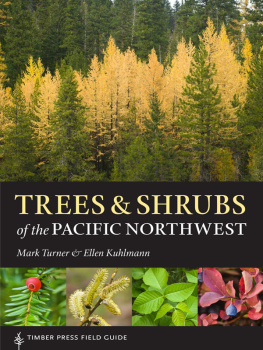

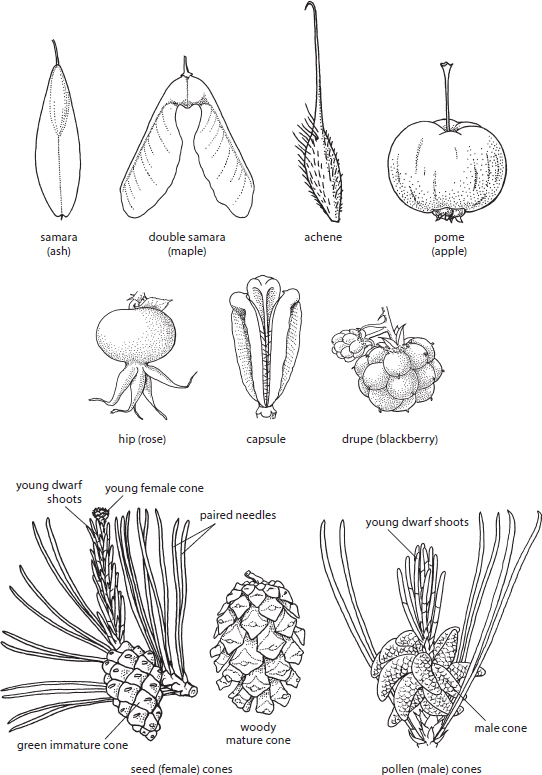

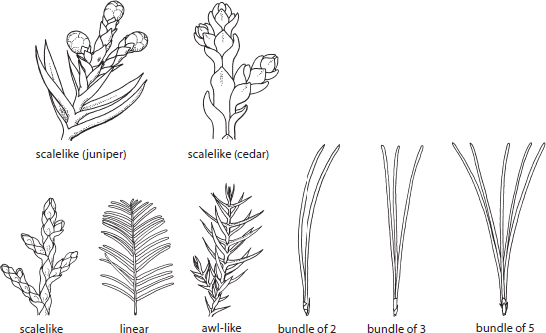

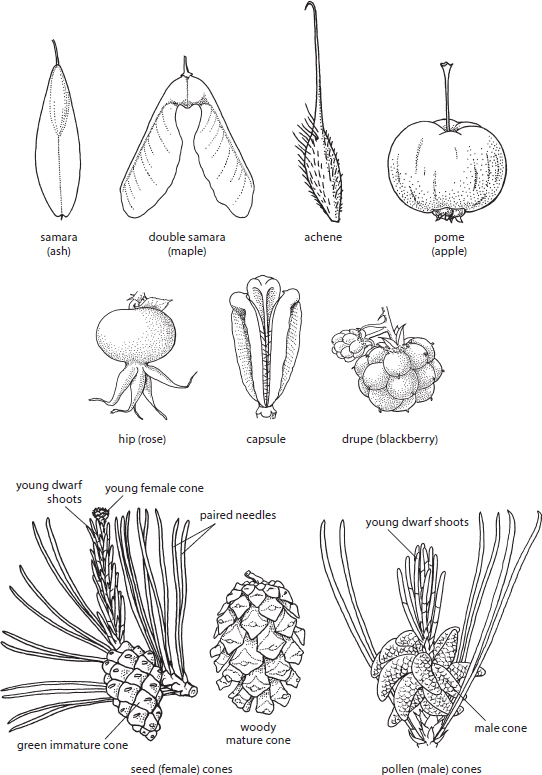

CONIFERS

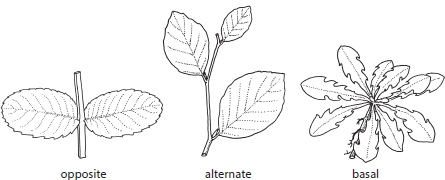

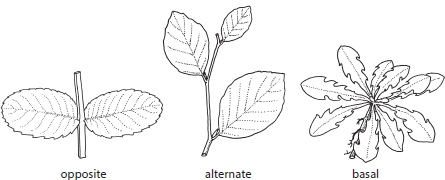

LEAF ARRANGEMENTS

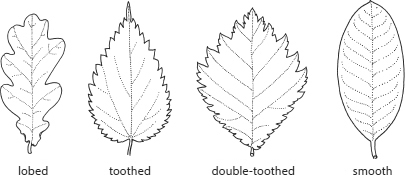

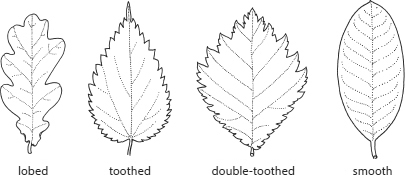

LEAF EDGES

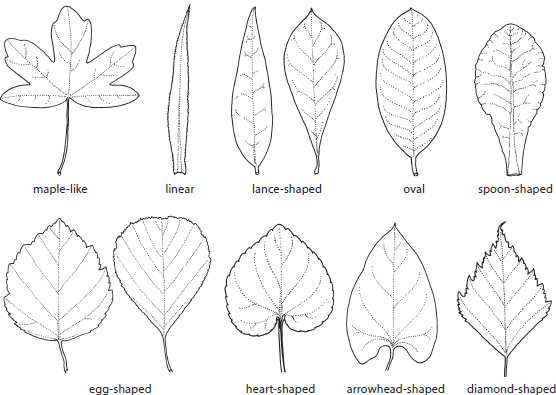

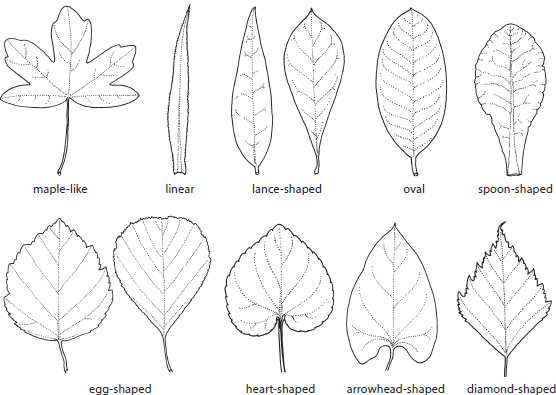

LEAF SHAPES

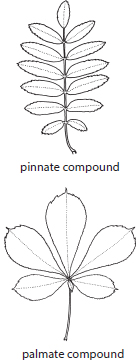

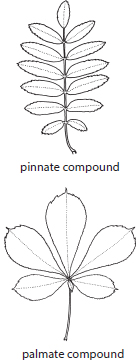

COMPOUND LEAVES

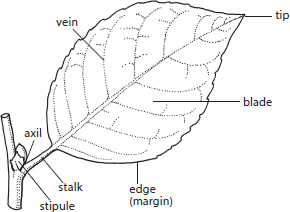

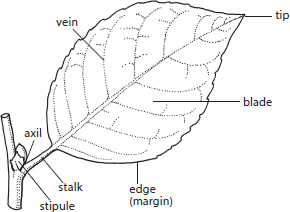

LEAF PARTS

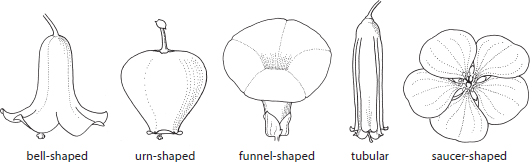

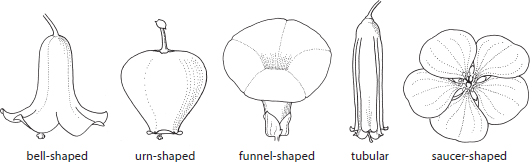

FLOWER SHAPES

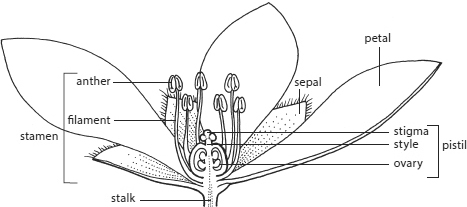

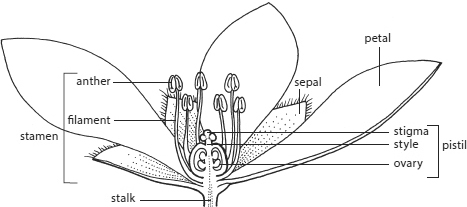

FLOWER PARTS

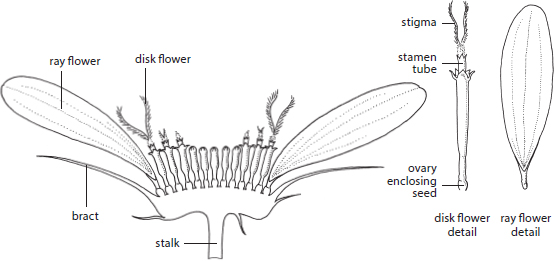

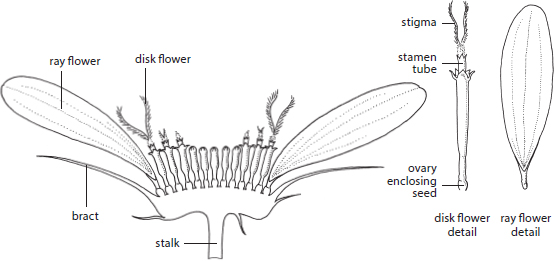

ASTER FAMILY COMPOSITE FLOWER

FRUITS AND SEEDS

TREES & SHRUBSof the PACIFIC NORTHWEST

Mark Turner & Ellen Kuhlmann

TIMBER PRESS FIELD GUIDE

To two lifelong learners

Al Hanners, who mastered the willows and sedges after turning 60, and Marie Hitchman, who at midlife decided to learn plant biology and coastal ecology so she could intelligently contribute to environmental issues.

They have shown us that much is attainable when you put your mind to it.

Copyright 2014 by Mark Turner and Ellen Kuhlmann. All rights reserved. Photographs by Mark Turner unless otherwise noted.

Published in 2014 by Timber Press, Inc.

The Haseltine Building

133 S.W. Second Avenue, Suite 450

Portland, Oregon 97204-3527

timberpress.com

6a Lonsdale Road

London NW6 6RD

timberpress.co.uk

Book design by Susan Applegate

Endpaper drawings by Alan Bryan

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Turner, Mark, 1954 April 8

Trees and shrubs of the Pacific Northwest / Mark Turner and Ellen Kuhlman.[First edition].

pages cm(Timber Press field guide)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60469-619-6

1. TreesNorthwest, PacificIdentification. 2. TreesNorthwest, PacificPictorial works. 3. ShrubsNorthwest, PacificIdentification. 4. ShrubsNorthwest, PacificPictorial works. I. Kuhlman, Ellen E. (Ellen Elizabeth), 1963 II. Title. III. Series: Timber Press field guide.

QK144.T73 2014

582.1609795dc23 | 2013036236 |

CONTENTS

PREFACE

Anyone who has spent time outdoors in the Pacific Northwest has likely marveled at a giant old-growth Douglas-fir and cursed a thicket of devils club. Alpine explorers may have been surprised to stumble upon dwarf willows no taller than the toe of their boot.

Trees and shrubs are almost everywhere in the Northwest. Maybe we take them for granted. We know that we once did, lumping understory shrubs into one homogenous boring shrub layer while searching for wildflowers or barreling up a trail in pursuit of an alpine summit. But the reality is that there is a great deal of diversity among our trees and shrubs, thanks in large part to the wide range of growing conditions in the Northwest. A few species, like Douglas-fir, western serviceberry, chokecherry, and common snowberry, are found in almost every county or regional district. Others, like our two rockmats, are very narrow endemics found in only a few places. The Klamath-Siskiyou Range is home to more conifer species than almost any other similar-size chunk of geography in the world.

When we began the journey that resulted in this book, we knew there were a lot of trees and shrubs to cover. Someparticularly those of the North Cascades, where we livewere familiar friends to revisit on each hike. Others, like the willows, had a vague familiarity but were often passed over because they were challenging to learn. Neither of us started on this book knowing everything we would discover along the way.

It stands to reason that our largest trees grow where the most rain falls each season. It takes a lot of water to produce a coast redwood, Sitka spruce, western redcedar, or Douglas-fir. Go east of the mountains to the Columbia Plateau or the Great Basin and youll find a landscape dominated by sagebrush, bitterbrush, rabbitbrush, and other small shrubs. In this arid part of the Northwest, what passes for old growth may be barely shoulder high.

Chaparral only touches the Northwest, with its northernmost examples just crossing the border from California into Oregon. Its a dense, nearly impenetrable shrub environment with many oaks, manzanitas, and ceanothus that were new to both of us.

We joked at the outset of writing and photographing this book that it was our excuse to learn the willows. That notoriously challenging genus taxed our powers of observation and frustrated us with the great variability within many of the species. We even thought about skipping them because theyre hard, but that would have been a disservice to you, our readers. We hope we havent led you astray because even after the time weve spent with the willows were far from experts. That takes nearly a lifetime of study.

This book would not have been possible without the work of numerous botanists and plant explorers who came before us. Their journeys and study laid the foundation. Some of them are memorialized in the names of trees and shrubs, people like David Douglas, Archibald Menzies, John Scouler, and George Engelmann.

While a few readers may gripe about the size and weight of this volume, we chose to err on the side of clarity and include at least a pair of photographs for most of the 568 taxa that have a main entry. We relied on the much larger, and much heavier, regional floras to identify specimens in the field and as primary sources for our descriptions. Books like Flora of the Pacific Northwest, its big brother Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest, and both the 1993 and 2012 editions of the Jepson Manual are well-thumbed references, in some cases held together by duct tape.

We also relied on several online resources, sometimes pulling up websites like CalFlora on a smartphone, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, to help identify a shrub. Mark relied on herbarium records, mapped through Google maps, to guide him to known locations for many species, following a line of red dots on the screen in the palm of his hand.

Next page