Contents

Guide

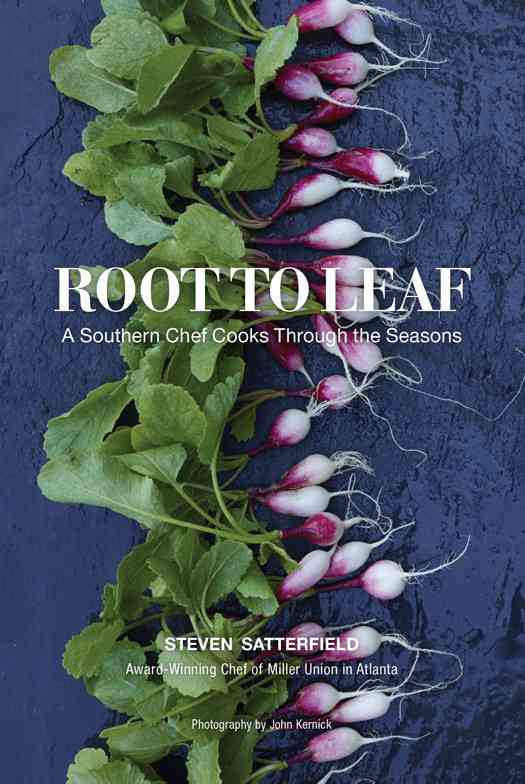

ROOT TO LEAF

STEVEN SATTERFIELD is executive chef of Miller Union, serves on the board of Slow Food Atlanta, started the Atlanta local network of Chefs Collaborative, and is an active member of Georgia Organics and the Southern Foodways Alliance. Satterfield was also nominated for Food & Wine magazines Peoples Best New Chef, following Miller Unions placement on the Best New Restaurants in America lists from Bon Apptit and Esquire, as well as Atlanta magazines Restaurant of the Year in 2010. The James Beard Foundation first recognized Miller Union as a semifinalist for the national award of best new restaurant in 2010. In 2013 and 2014, he was named a semifinalist for Best Chef: Southeast by the James Beard Foundation.

Discover great authors, exclusive offers, and more at hc.com.

Art direction and design by Erika Oliveira

Cover photography by John Kernick

One hour. 23 minutes. 12 seconds. I glanced at the countdown clock on the East Atlanta Village Farmers Market website. It was ticking down to the late-afternoon season opening and I made a point to arrive right on time, knowing it would be swarmed. It was the first warm day of spring and the market was teeming with energy. I ran into an old acquaintance who seemed a little more than disappointed with the spring offerings. I guess its just really early in the season? He shrugged as he disappeared from the scene, empty-handed. I did a quick scan of the market booths and wondered what he meant. Where my friend saw nothing, I saw possibility.

I picked up a few bundles of greens, some spring garlic and leeks, some fresh pasta, a pint of berries, a young cheese, and a little basket of tender mushrooms. The wheels in my head were turning and I already had dinner figured out: melted leek ravioli with mushrooms and green garlic; a salad of tender baby chard and dandelion greens; a hunk of artisanal bread; some macerated strawberries with a delicate sheeps milk cheese; a chilled bottle of ros. Later that evening, as some friends and I enjoyed this delightful spring meal, I kept thinking about the disappointed fellow at the market. His mind-set is all too common. Even regular market goers who aspire to cook fresh producedriven meals are often stumped when they have to decide what to put on the table.

Americans have been conditioned to believe that more is better. It is a first-world problem to have everything you want, anytime you want it, and this type of thinking has done some serious damage to our food systems and collective health. Unlimited options clutter our minds and stifle our imagination. We are out of touch with the earths rhythms and we do not allow ourselves to appreciate the anticipation of the natural cycles of the seasons. I use these seasonal variables as guidelines, rather than limitations, when I buy fresh produce.

Ive learned that if you are able to show up with an open mind and some empty bags rather than a shopping list, you can respond to what is available. Allowing the fresh produce to guide you is true seasonal cooking. Its what this book is all about. Yes, I have the advantage of many years in professional kitchens, and this has honed my skills for thinking on my feet. But I still remember the growing pains of making mistakes and learning from them. In writing this book, I am distilling the lessons Ive learned to empower you to shop for, select, and create delicious meals regardless of where you may reside. I am fortunate enough to live and work in a locale with extraordinarily rich diversity, and while I realize every region has different climates with varying access to fresh food, with the right information, you can cook like this too.

When I am deciding how to use a fruit or vegetable, I consider several things:

Texture: Is it crisp, tender, starchy, juicy, seedy, or stringy?

Flavor: Does it taste sweet, chalky, grassy, bitter, or sour?

Shape and Size: Is it large, petite, round, oblong, heavy, or flat?

Color: Is it bright green? Will the color deepen? Does it look fresh? Will it turn brown if I cook it?

Challenges: Is it thick-skinned, hard-shelled, thorny, gooey, time-consuming? Do I know how to cook it? Do I know how to get started?

One bit of advice that I often give people when they are working with fresh produce is to taste it in different stages of cooking. Try it first raw. If you are blanching green beans for instance, taste them several times while they are cooking. You will notice that they go from a dull green with a chalky taste to a tender crunch with a lot of sweetness and a bright green color. Thats the moment when you want to pull them from the water and plunge them into an ice bath. Think about the advantage you have that you can actually taste vegetables when they are raw. You cant do that with your chicken dish from start to finish, can you?

When I first started cooking professionally, vegetables were more or less an afterthought and most of the focus was on the protein. The idea of Southern food as something noble and respectable was just catching on. And as I grew more and more interested in the local farming community, I thought to myself: why not start a restaurant where we can react to everything that is in season and incorporate all that is harvested? Miller Union was born from this idea, and even though we serve plenty of meats, our focus is on the world of seasonal produce. When we write the menu or test ideas, we are always referencing the farmers current availability lists.

But before I began my culinary career, I was on a different trajectory. I grew up on the Georgia coast in Savannah, Americas first planned city. I was never afraid to cook, and in fact was quite comfortable in the kitchen. I used to rummage through drawers and cabinets, playing with the spice containers and sniffing each one, memorizing the smells. When I was a teenager, I would volunteer to make dinner for the family, opening up some cans or packages from the freezer and heating them up, and doctoring them, to suit my taste.

I moved to Atlanta in the late 1980s to attend architecture school at Georgia Tech. It was there that I got my first taste of living on my own. If I had enough money to go to the store, I would make my own food. My roommate at the time was always happy when I did because I usually made too much. I spent my final year abroad studying in Paris, France, and fell in love with the Parisian lifestyle of shopping on the streets of the march with all of its specialized little storefronts. You simply walk from shop to shop on your way home and pick up what you need for the next day: bread, cheese, vegetables, fruits, and wine. I couldnt afford to purchase meat, and the markets there inspired me to cook simple but satisfying vegetable-based meals on the single electric burner in my tiny one-room apartment.

From Paris, I returned to Atlanta, only to realize that my heart was not in the field of architecture. So I did what any twenty-one-year-old would do on his first summer off after sixteen years of schooling. I checked out. I picked up a guitar for the first time and started learning how to play and write songs. Just over a year later, I formed a band called Seely with some friends from college and we quickly and strangely became widely known and started climbing the college charts. We had the opportunity to play live shows all over the country and lead a fantastic life. But it wasnt lucrative, so I turned to restaurants for supplemental income. I was working in short-order kitchens, but as we matured and took more time off between records, I sought out better food. I was lucky enough to land a job at local chef Anne Quatranos Floataway Caf, one of the first real farm-to-table restaurants in the city. After that I started working under acclaimed Southern chef Scott Peacock at Watershed in Decatur, Georgia. Scott focused on traditional Southern cooking with seasonal flair and it was there that I planted my roots. I worked every station and eventually ended up running the kitchen. After nine years, I decided to go out on my own. With the help of my trusty friend and soon-to-be business partner, Neal McCarthy, I started Miller Union. I was beginning to realize that I had a knack for coaxing flavor out of just about any fruit or vegetable, and I wanted to explore it.