ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

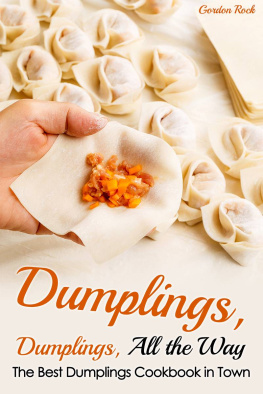

So many people pitched in to make this book happen that its hard for me to show my gratitude adequately. First and foremost, Id like to thank my wife, Maria Asselle, who had dumplings for dinner on nights when she dreamed of something else far more often then I care to admit.

I also offer special thanks to the chefs whose dishes gave me a benchmark to reach for. Some, like Yamini Joshi, Jessica Avent, Jim Weaver, and James Griffiths, spoke to me at length, while othersbecause of time and language barrierscould respond with only a smile or a nod. No matter... every lesson learned was important.

Finally, a special thanks to everybody at Countryman Press for creating this new edition. The dumpling universe is forever changing and keeping up with new developments is no small task.

CONTENTS

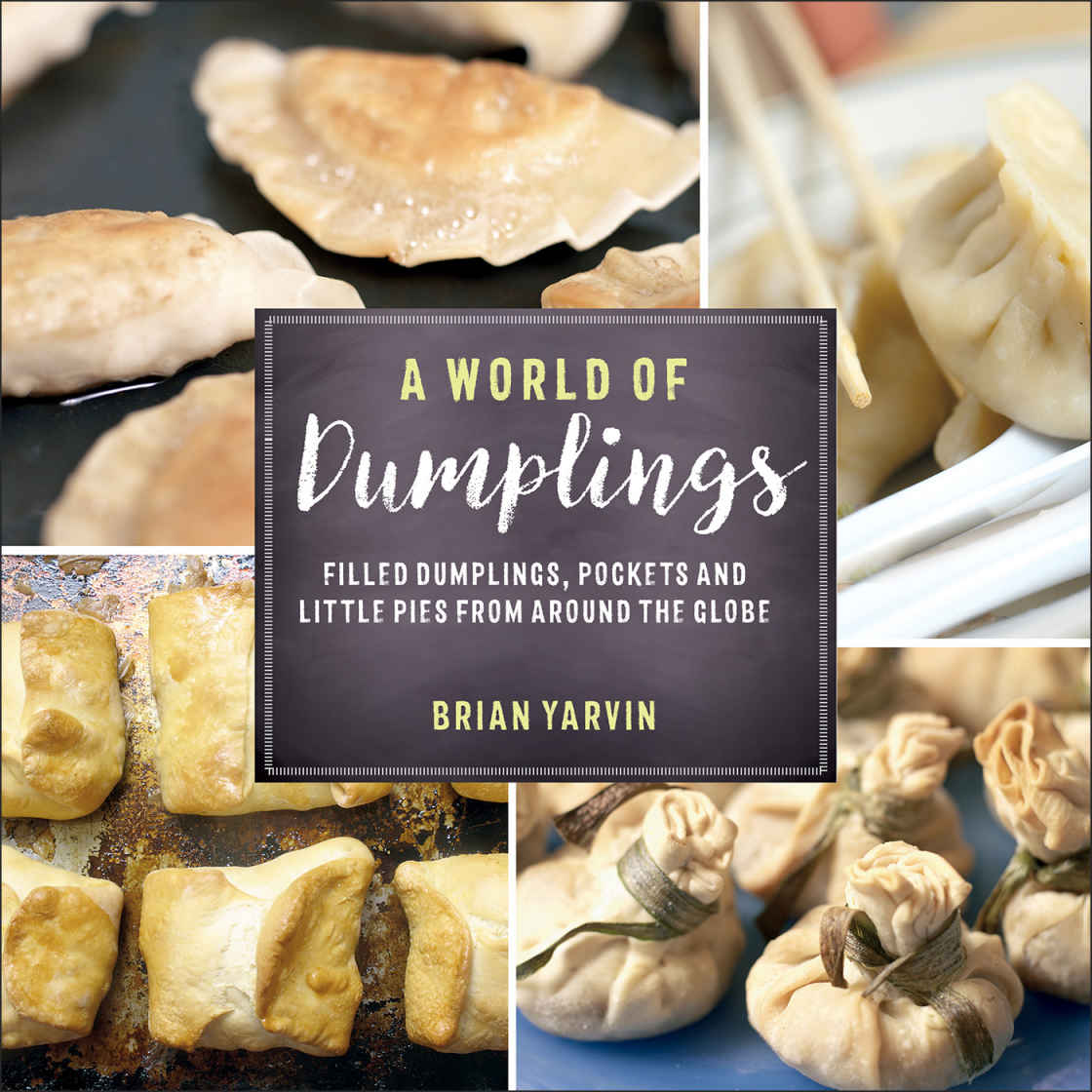

At lunchtime in Cornwall, England, youll see people eating a local specialty: a sheet of dough wrapped around meat and vegetables to form a sort of self-contained meal. Thousands of miles away in South America, crowds gather around a vendor offering a snack: a bit of meat and vegetable wrapped with a piece of dough. In China, Italy, Japan, Poland, Turkey, and a host of other countries, this scene is repeated every day. The dumplingthe most universal of all foodsis everywhere.

Dumplings are a common thread in cuisines throughout the world, similar in basic concept but often wildly different in the details. The ones from Cornwalltheyre known as pastiesare bigger than a mans fist and have a flaky crust, while the pelmini of Eastern Europe are smaller than a fingernail. Vietnamese spring rolls have a wrapping so delicate its almost transparent, and Polish pierogi have a skin thats thick, almost chewy, and redolent of sour cream.

What is it that unites these far-flung foods? Is it more than just a rough description? And how do these common items show their differences? In this book, we will explore what makes pierogi Polish and mandu Korean. Well find out how gyoza differ from shu mai , and why all of them are different than ravioli.

You could travel the world in search of the essential dumpling, but theres really no need. Modern America provides countless opportunities to sample every variety imaginable: Cornish pasties in your local pub, shu mai at the Chinese restaurant, ravioli from a neighborhood Italian deli, and pierogi at a church supper. Taken as a category, dumplings transcend all barriers. You can grab them at a snack bar or spend an afternoon making them with friends and family. Theres a bit of joy inside each one.

A World of DefinitionsOr Just What Is a Filled Dumpling, Anyway?

One of the first questions that people ask me is: Just what is a filled dumpling, anyway? Followed by, What makes it filled? The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines dumpling as (a) a small mass of leavened dough cooked by boiling or steaming or (b) a usually baked dessert of fruit wrapped in dough. This sounded pretty good to me, although the leavened part means that pierogi, ravioli, and most of the Chinese section wouldnt qualify.

I sought out another definition, this time from The Food Lovers Companion , second edition, by Sharon Tyler Herbst: Savory dumplings are small or large mounds of dough that are usually dropped into a liquid mixture (such as soup or stew) and cooked until done. Some are stuffed with meat or cheese mixtures. Dessert dumplings most often consist of a fruit mixture encased in a sweet pastry dough and baked. Theyre usually served with a sauce. Some sweet dumplings are poached in a sweet sauce and served with cream. I liked this definition a lotespecially the part about poaching in a sweet saucebut it still left out ones that were steamed, boiled in water, baked, or fried. In other words, almost every dumpling that I knew.

This called for a new definition, one that would allow for all sorts of foods commonly known as dumplings to be included. So... just what is a dumpling? More specifically, a filled dumpling? How about: a food item that consists of a dough-based outer wrapper with a distinct, separate filling inside?

... Wrapped in Dough

One thing that all the recipes in this book have in common is dough. There may be every sort of filling, but theres always that stuff on the outside. So for that reason, well begin with a few words about dough making. Theres something very gratifying about it. Maybe its the kneading with its vigorous action or perhaps the primal-ness; after all, flour-water doughs are among the earliest known cooked foods.

Viewed collectively, the doughs here have an astounding range of ingredients; everything from mashed potatoes to curry powder can find its way into a recipe. But all share wheat flour and water.

Just what does wheat flour do? Besides being a great source of carbs, it contains a specific kind of protein thats pretty much the only source of gluten that gives dough its texture. You can do lots with other grain flours, but theyll never knead into the sort of dough that wheat will.

Gluten is a mixture of wheat protein and water with a unique feature: When kneaded, it has elasticity. With a bit of work, it can stretch and form the distinctive consistency that we prize in breads, cakes, and pastas. The recipes here take advantage of this in two ways. Yeast-raised doughs become lighter with their distinctive body, and pastas become chewier and acquire that al dente character.

Not all recipes have long kneading times; the ones closest to pie doughs are kneaded only for a few minutes. That way they build up enough gluten to hold the dumpling together but not enough to make it tough.