Contents

- Part 1: Making music out of silence

Conversations with Martin Meyer

Guide

Contents

Conversations with Martin Meyer

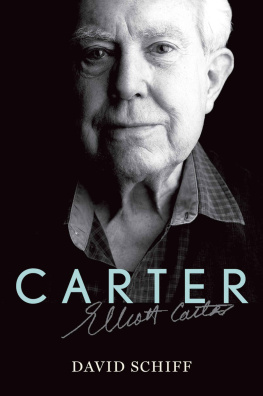

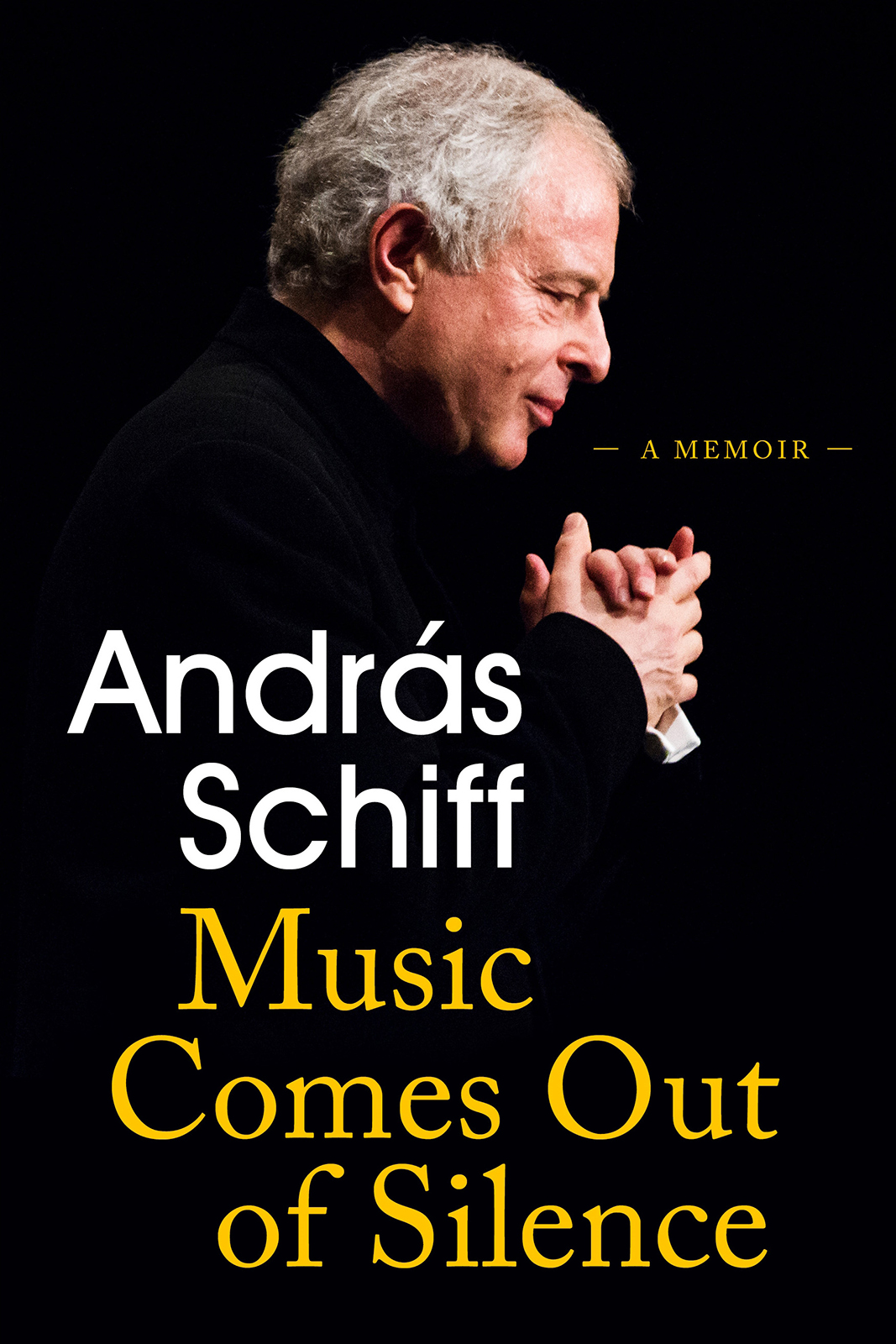

All music is interpretation. Each musical text offers its readers guidance and direction on how to bring that music into existence. But behind every command or notation lies the imagination, and it is this that brings the music out of its silence, out of mere possibility, into performance in the here and now. Few musicians have thought about this process, as music moves from idea to reality, as intensely and precisely as Andrs Schiff. Pianist, conductor, scientist and commentator, he is the product of numerous qualities and experiences. And in the end, music is about the performance, expressed as a statement that can be understood in the present day and beyond.

Schiff did not become a virtuoso in order to further his own ends. Even in his youth he had a deep awareness of the responsibilities for ones own actions. Indeed, he views music as a combination of not only work and research but also spirituality and conscience, and all this is expressed through the masters, from Bach to Haydn, Mozart to Beethoven, Schubert and Schumann to Brahms.

Schiffs ability to combine intellectual tension with the sensual qualities of playing is singular. In other words, when we hear Schiff perform, we cannot help but recognize that a truly attentive musical mind must not only read the music, but consider it, guide it, even argue with it in order to produce truly great sound. For nothing would be gained if the many insights, research, knowledge and reflections involved did not lead to sound.

This book is all-encompassing, in the same sense as a tour dhorizon, addressing the essential points of biography, while exploring the secrets and adventures of music with a view to its design. Schiff proves to be a generous partner in conversation, discussing a multitude of topics with verve and passion, as well as his well-known and often self-deprecating sense of humour. Above all else, one thing is clear: the vocation of a musician does not come about by itself or because of some latent ability or talent. It requires patience and a great deal of hard work. No example is more illustrative of this than the fact that Schiff did not dive into the cosmos of Beethovens sonatas as a talented young man, but instead, did so only relatively recently, having invested a lifetime of preparatory work.

This book is comprised of two parts. The second part contains a rich series of essays, analyses and portraits. Schiff writes about his favourite works and composers in a precise and inspired way and many of them will be familiar to you. This doesnt make an essayists job any easier! On the contrary, the whole world seems to know what Bach, Schubert, Mozart or Mendelssohn should sound like. Sometimes it seems as if weve heard it all until we listen to Schiff, who brings something newer, more exciting, more profound, and clearer to the table. These writings stand as testaments to Schiffs talent for the written word.

The first part shows conversations that Andrs and I had at regular intervals over the course of two years. These conversations always seemed to me to be like music, just waiting to be launched from silence.

Martin Meyer

Zurich, January 2020

Conversations with Martin Meyer

Lets begin with a fundamental question: what for you is the meaning of music, what is its essence?

To begin with there is silence, and music comes out of silence. Then comes the miracle of highly varied, progressive forms growing out of sounds and structures. After that, the silence returns. And so, silence is actually a prerequisite for music. But going on from that, music of course means much more to me personally, because its my life. It can never be reduced to mere material standpoints, even though repeated attempts to do that have been, and still are being made. Music essentially has to do with the spirit and the spiritual.

And, of course, with the soul, with emotions.

You could say that music essentially comes from the soul. That, by the way, differentiates people from animals. Some birds make wonderful music just think, for example, how Olivier Messiaen reacted to that in composing. But the difference can perhaps be understood through a comparison. When swallows build a nest its something we certainly admire, but at the same time we wouldnt call it high art or architecture. What differentiates Florence Cathedral from a swallows nest? The deliberate intent to create a work of spirit and soul. And so theres also a fundamental difference between the song of the nightingale and Bachs The Art of Fugue.

To what extent does music affect you in a religious sense?

Quite a lot. When I occupy myself intensively with the works of Bach or the string quartets of Beethoven, I hear and feel things which cant be explained in purely rational terms. And so I hope that the music doesnt simply become extinct, but that each note somehow remains stored in the cosmos, perhaps transformed, but in any case doesnt become lost.

What happens when you perform the music yourself? What considerations come into play?

I try to listen very attentively. Essentially, its a question of following the sounds I produce with a third ear. The better developed this third ear is, the better the musician is, too. I had already developed this gift as a student and was encouraged by my teachers to listen inwardly. Thats why its dangerous and even disastrous to sing out aloud while playing the piano. People think they can hear well at the same time, but thats a mistake. Its the piano that has to sing, not the pianist.

Music differs from other arts in being organised in time and having fixed points between its appearance and disappearance. On top of that, its the least representational of all the arts in its high level of abstraction. For practising musicians, thats another immense challenge.

In addition, theres the fact that as a rule, unlike literature music is multilayered. Disregarding Gregorian chant and other related monodies, and concentrating in particular on the piano, music is almost always polyphonic. You have to play several voices as though several theatrical actors were enouncing their texts simultaneously. That virtually never happens on the stage. Thats why music demands the highest concentration particularly with Bach, in a four-part fugue, for instance, where all the voices are equal.

Weve talked about disappearance. Again, in comparison with other arts, but also taken in isolation, the classical music we know and are considering has had a very short existence, barely six centuries up to now, so we dont know how its going to develop further.

Thats interesting, and perhaps worrying, too. Mind you, there have been certain cycles in the other arts, if we think, for instance, of Italian or Dutch painting. High points are followed by declines and barren periods. In music, I look at it like this: Western music reaches an absolute peak with Bach; then it experiences a second golden age in the Viennese classics up to the death of Schubert, in 1828. There are further productive periods with the romantics and late romantics, as well as the music of the early twentieth century. After that theres a comparatively long period of static development. Or to put it more provocatively, if we wanted to compile a list of musical masterpieces composed since the Second World War, it would be terribly short.