NO, YOU CANT BE AN ASTRONAUT

PATIENCE FAIRWEATHER, PHD

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions, or for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein.

Copyright 2020 Patience Fairweather

ISBN: 978-1-943476-61-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2019950090

Cover and interior graphical elements by Freepik and Vecteezy.

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Plausible Press.

DEDICATION

This book was inspired by my students.

I hope it helps.

CONTENTS

T HANKS TO FAMILY, FRIENDS , colleagues, and indefatigable researchers whose work informs this book.

1. HOUSTON, WE HAVE A PROBLEM

J OHN DID EVERYTHING right.

He went to college right after high school, to the most exclusive place he could get intoa big-name research university with Nobel laureates on the faculty. He had heard about the crisis-level shortage of STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) majors [1], so he chose to major in environmental science.

John wanted to graduate in four years, so he concentrated on his schoolwork. He turned down opportunities for internships and study abroad, as they would have lengthened his time to degree. He never met any of those Nobel laureates on the faculty. They worked mainly with graduate students, it turned out; undergraduates like John never saw them.

John graduated with a decent GPA and expected to earn enough to pay off his student loans quickly. Unfortunately, competition for the few desirable jobs was fierce, and many vacant positions were in remote areas. They offered no moving allowance or job security, and the pay was disappointingly low. John found his situation wasnt unique; 29% of graduates in his field were working part-time, and over half were in jobs that didnt require a college degree at all [2].

After a few months of job-hunting, John was out of money and options. He now works a part-time job. His employer limits his hours to avoid paying benefits. He cant get another degree now; not only can he not afford the tuition, but hes now one of the 80% of hourly workers with an unpredictable on-call work schedule, which prevents him from being able to attend classes [3]. He could get an additional degree online, but hes not sure it would be a wise investment. Online education isnt as well-respected as its traditional face-to-face counterpart [4, 5]. Fortunately, his parents are keeping him on their health insurance...for now.

Johns story is not unusual. Although fewer than five percent of recent college graduates are unemployed, an additional 41 percent work in jobs that typically dont require a college degree [6]. And as he found, its not just the much-maligned art history (56%) or ethnic studies (50%) majors who are taking your coffee order or folding shirts at the mall. 73% of criminal justice majors and 60% of business management majors are working in positions that typically dont require a college degree.

And it turns out there wasnt really a shortage of STEM workers after all. While politicians and pundits were banging on about the need for more STEM graduates, the evidence showed that the STEM shortage is largely a myth. Schools in the U.S. churn out more STEM graduates than there are available jobs, leading to oversupply in some fields [1, 7, 8].

How did we get here?

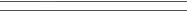

The college degree used to be rare. In 1950, only six percent of U.S. adults over 25 had a four-year degree or higher. It was a credential that really stood out. But today, around one-third of U.S. adults over 25 have a four-year degree or higher. The college degree today is about as common as a high school diploma was in 1950 [9].

Now philanthropists and policymakers are pushing to get even more people to go to college [10], aiming to have up to 60% of the population holding a postsecondary degree [11]. Supporters of increased rates of college degree attainment cite the fact that people with college degrees earn more, on average, than people without them [12]. The claim is then made that increasing the number of college graduates will result in improved wages for graduates and non-graduates alike. This rests on two assumptions:

1) The demand for college graduates will rise to meet the supply, and

2) There are enough good (high-paying, stable) jobs out there to absorb the increased output of college graduates.

The first assumption is correct. Given a choice between two applicants, employers prefer the more-qualified candidate. What this means is that companies will now hire college graduates for jobs that used to require only a high school diploma. Thats the source of the college premium: College graduates are filling the jobs that high school graduates used to get [13].

U NEMPLOYMENT AMONG those with high school only has gone up at the same rate as college attainment. Sources : www.epi.org/publication/the-class-of-2015/ and nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d15/tables/dt15_104.10.asp

Increasing the number of college graduates has not coincided with an increase in good jobs for those graduates; in fact, the opposite has happened. Since 1980 average income has decreased, the number of poverty-wage jobs has grown, and the percentage of jobs that are temporary or on-call has gone up [14].

Claims of an undersupply of college graduates have been contradicted by the evidence. For example, a 2010 Center on Education and the Workforce study projected that by 2018, 33% of all job openings would require a bachelors degree or higher, while an additional 30% would require some postsecondary education [15].

As of 2019, according to the Department of Labor, only 21% of jobs in the United States required a bachelors degree, and an additional 11% required an associates degree, certificate, or some college. 63% of jobs required a high school diploma or less [16, 17].

Next page

![Meri Koval - Articulated Restraint [Lady Astronaut #1.5]](/uploads/posts/book/868242/thumbs/meri-koval-articulated-restraint-lady-astronaut.jpg)