NoteFeatures pages are listed in italics.

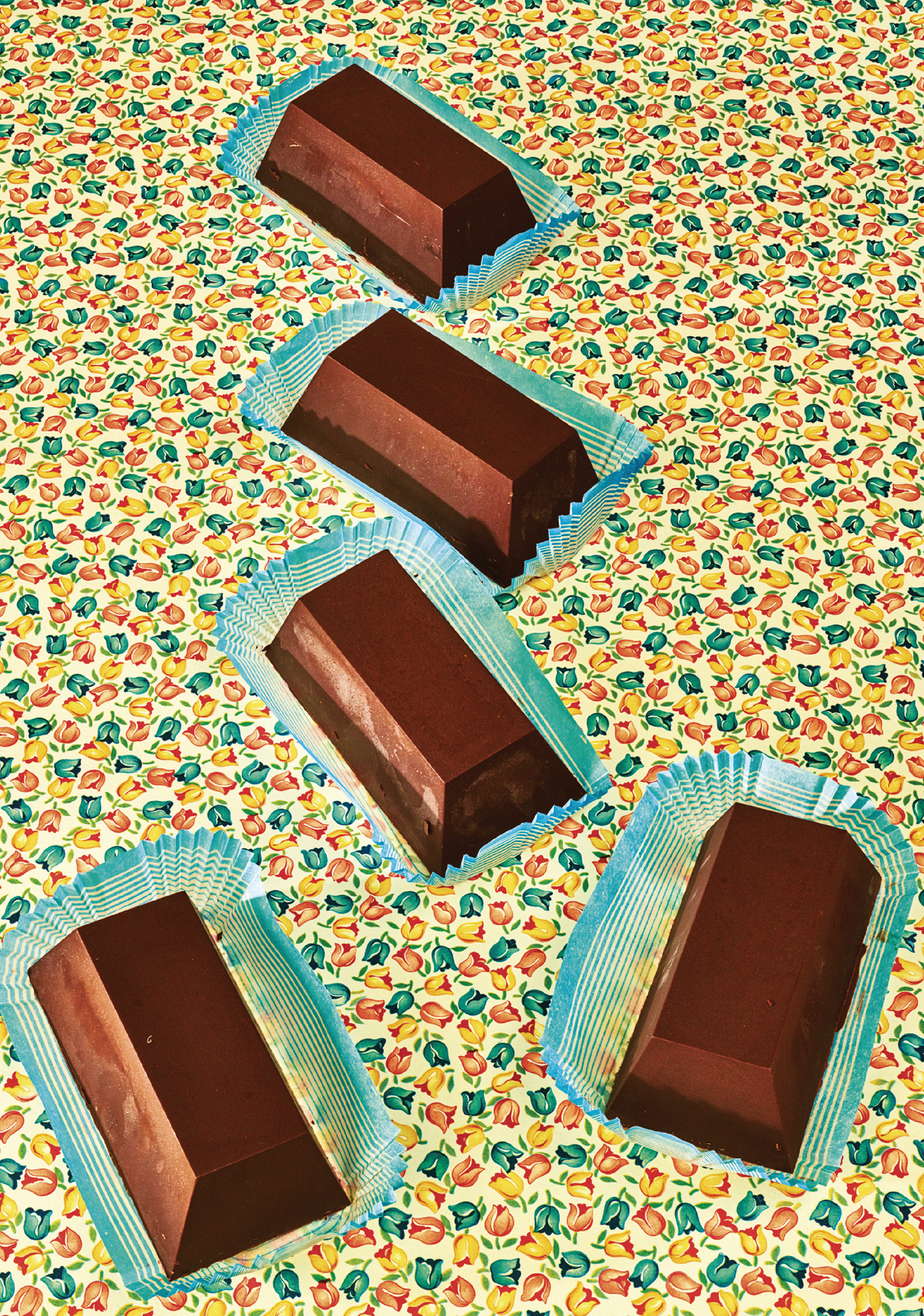

Ice cream was not so hot when I was growing up. It was usually limited to the summertime treat of a 9 pence orange Sparkle (a fluorescent ice pop) in the park after school, or the occasional slice of a supermarkets economy sticky yellow vanilla brick (a rectangular length of ice cream wrapped in cardboard). This would melt and refreeze over the course of being served from its damp box, and turn into a curious foamy gum. But I still loved it.

As a teenager living at home in suburban Twickenham my favorite cookbook was Cuisine of the Sun by Roger Verg, an inheritance from my godmother (and one half of the Two Fat Ladies), Jennifer Patterson. The recipes in it demonstrate the use of simple harmonies to enhance the flavor of each ingredient, while still allowing the beautiful, natural produce of Provence to shine. Verg called it cuisine heureuse. It left me pining for something brighter than the supermarket foods Id grown up withsomething transportive and sun-kissed.

It was a relief to leave school, which I hated and had only a string of failed A levels to show for. I went to art school and, to pay the bills, got a job at age 18 working as a greengrocer on the forecourt of the Bluebird Garage on the Kings Road. I spent a lot of time spraying arugula with an atomizer, while the real work was done by Alf. He arrived early from the market in Milan with a van full of beautiful fruits and vegetables, from moonlight-yellow pears wrapped in inky, indigo sugar paper to bunches of dusky black grapes tied with shiny lilac florist ribbon.

I dropped out of art school and spent the summer of 2000 in Marseille instead. On my return to London I read a newspaper article about a man called Lionel Poilne who was opening a bakery in London to make this stuff called sourdough bread. I got the bus straight over to the Pimlico shop to find the doors wide open and the shop still being built, with Monsieur Poilne overseeing the installation of a vast brick oven. I was emboldened after my summer speaking French and introduced myself to him, winning myself the position of Poilnes first (andfor some yearsonly) British shop girl.

Paris

It was a hard sell at the beginning, with the bread at an eye-watering 5.90 per loaf. People would come in asking if we made sandwiches or sausage rolls or pies, and we had to try and encourage them to taste the bread: the miraculous flavor of its crackling crust a result of the magic that can be achieved from just a few essential ingredients: flour, water, and salt. I worked as an assistant at the London shop and spent some time at the Paris branch. In Paris I lived in a room above the bakery itself, and the smell of those huge burnished loaves of sourdough bread baking in the ancient brick ovens got me out of bed to work at 5:30 every morning. But although I loved that company, and the chewy crust of that bread, I was looking for something else.

Each morning during the spring of 2001 as I got ready for work I had the telly on in the background. It was screening live segments from the Cannes Film Festival. A clip showed pop stars singing on the beach and their hair looked really shiny. It seemed glamorous and appealing. Then I remembered that Roger Verg, author of my favorite cookbook, had a restaurant and cooking school in Cannes.

Poilne was friends with Verg and when I handed in my notice and bought a one-way ticket to Nice, he handed me a personal letter of recommendation to give to him. He asked Verg to take care of me and wrote that I sold bread as though I were selling diamonds. I still have that letter in a suitcase, because pathetically I was too shy to give it to Mr. Verg. I didnt have the confidence to work in a real kitchen. But I couldnt face going home, and so instead I took a waitressing job at a beachfront hotel, and started a new career as Cannes worst waitress.

Cannes

It was incredibly unglamorous. I worked 16-hour shifts in tennis shoes, nude tights, and a pleated aertex miniskirt. But that was when I found an ice cream shopa little glacire with tinted glass windows and green leather banquettes just off the Croissetteand began a daily ritual. After a swim in the sea and before work, I would eat ice cream sundaes for breakfast.

The menu board changed daily and the flavors dazzled me: cerise, abricot, cassis, groseille, saffran, and calisson. It was nothing like ice cream in the UK. I was astonished by the texture and how they captured the fresh taste of an ingredient in a frozen scoop. I puzzled over how it was made, and the ice cream seed was planted.

On my days off I took the train along the coast to Italy. Ice cream specialities in Piedmonte were hazelnut, coffee, and latte Alpinaeven violet Pinguinos (choc ices)and in Liguria, green lemon and bergamot. People seemed to go for an ice cream and a walk the way we in the UK go to the pub. I walked and walked, discovering markets and eating ice creams.

Back home that winter, working another stopgap deli job, I read