CONTENTS

Over the past few years, the term Scandi has become a byword, a shorthand for a particular brand of minimal, effortless cool. And though our crime writers have a knack for depicting a land full of darkness and horror, in actuality Scandinavia is more often spoken about as a kind of utopia, an image bolstered by affirming statistics on health, equality and well-being. Sweden, in particular, is hailed as the ideal place to live and whenever I mention where Im from people frequently sigh and respond: they seem to have got so many things right over there.

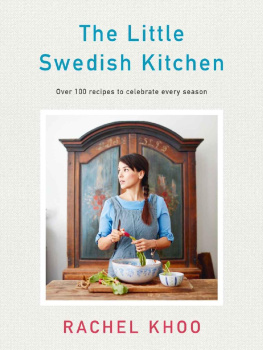

When it comes to our food, however, few people seem to know very much about it beyond what can be found at IKEA. Perceptions seem to fall into one of two categories: either outlandish New Nordic gastronomy with a side of moss and ants or, at the opposite end of the spectrum, homely meatballs in cream sauce, beetroot and enough dill to fill a field.

This doesnt really paint a picture of the food that I grew up with or the meals that my Swedish family and friends cook back home. Sure, from time to time every Swede pines for some husmanskost the traditional and thrifty home cooking that mormor (maternal granny) makes: salmon pudding, game stew, potato dumplings, oven-baked pancakes studded with crispy bacon and, yes, meatballs. But everyday Swedish food has evolved over the years, embracing a variety of ingredients, cultures, cooking styles and, above all, placing a much greater emphasis on balance and health.

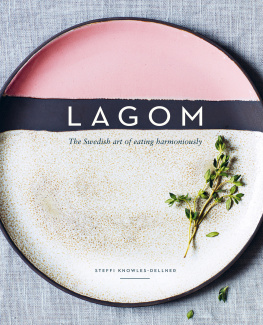

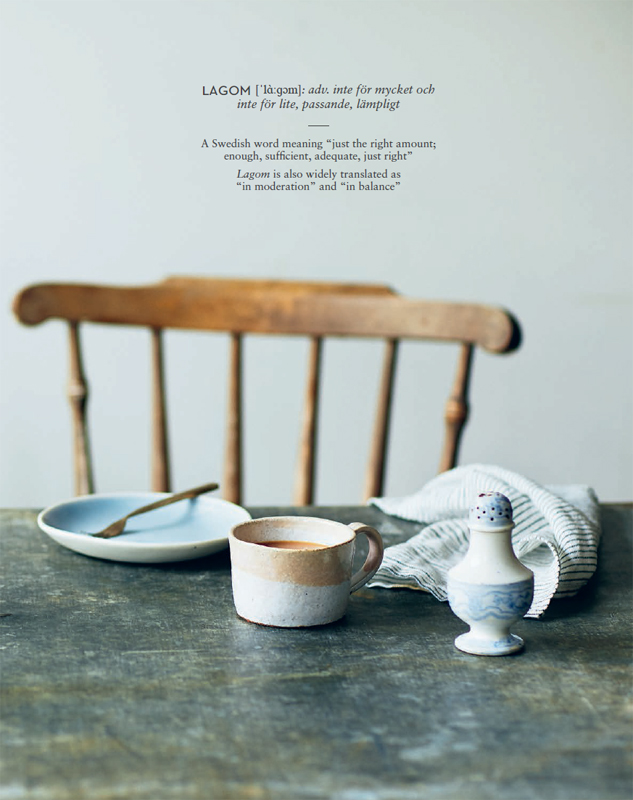

LAGOM IS BEST

For me, the word that encapsulates the way we eat in Sweden is lagom. The Swedes themselves are the first to admit to their peculiar attachment to this small, loaded word, even to the extent of joking about how lagom they are. Lagom r bst (lagom is best), they say, rolling their eyes.

Notoriously difficult to translate, lagom can be used to describe almost anything: you can be lagom well, your friend can be lagom tall, your coffee lagom strong and the weather lagom warm. But to dismiss it as simply a quantifier would be to underestimate its importance. Lagom goes right to the heart of Swedens national psyche and characterizes everything from Swedens political leanings and stance on gender equality to their aversion to anything too ostentatious. It is at the core of many typically Scandinavian ideals like fairness, consensus and equality.

And while this may sound like a doctrine of restraint, it is in fact anything but. Lagom is simply a manifestation of equilibrium work and play, light and dark, hot and cold, wealth and poverty, tradition and modernity. You can find lagom in our distinctive seasons, our high taxes, understated design and deep appreciation of quality, innovation and progress, so long as it isnt too over-the-top or flashy a bit like our sturdy Volvos and Saabs.

Not surprisingly, lagom extends to our cuisine as well the Swedes take great pride in eating healthily, drawing on their own cooking traditions and the seasons offerings. But they also know when its time to break the rules and reach for a cinnamon bun or add a dash of sumac or chilli. Whether enough is as big as a feast or as small as breakfast, Swedes know how to celebrate life through food.

For us, eating has never been about extremes swinging from one day to the next between excess and denial but about harmony and enjoyment. Taking time to eat well, but also according to your means, the seasons and environment, while not shutting out pleasure or the rich food world beyond Scandinavias borders these are the core food philosophies that come naturally to Swedes.

THE NORDIC DIET

With their generous holiday allowances, extensive parental leave and work/life balance, there is time to spend in the kitchen, preparing more food from scratch. This is in part what contributes to a focus on health and eating well that is taken for granted in Sweden. Certainly, when I was growing up, overly sweet, processed food and drink did not enter the house: they simply didnt belong there. Instead, breakfasts were based around whole grains and dairy (often cultured products like filmjlk, a soured pouring yogurt) that set you up for the day; dinners always featured plenty of the hearty vegetables that grow in our cold climes; fish was enjoyed as often as meat; and puddings were treats that didnt make your teeth ache. Berries, rapeseed oil, root vegetables, nuts, rye, oily fish, game, unsweetened dairy products these are the bread and butter of Scandinavian cooking and remain the staple ingredients in my kitchen today.

Well put spelt flour into our cinnamon buns or even make them gluten- or dairy-free. Weve become experts at sneaking goodness into our cakes and bakes by using a range of flours, adding nuts, seeds, fruit and even vegetables something weve been doing long before it was trendy.

There are precedents for this. Many of our traditional baked goods were already relatively low in sugar; even our famous cinnamon buns are created from a cardamom-laced bread dough which only has a fraction of the sugar you would find in the UK equivalent. Our beloved pick n mix is limited to one day, known by every Swedish child as lrdagsgodis Saturdays Sweets.

A lagom approach recognizes that these little indulgences are important, vital even, in the celebration of life through food, but they are evened out by a varied diet, getting up and moving about and not overindulging. A little of what you fancy does you good and life is far too short not to eat cake

LAGOM THROUGH THE SEASONS

This harmony can also be seen in the seasonal way that the Swedes eat. There is no shortage of Swedish holidays and festivities throughout the year, from the bonfires of Walpurgis Night in late April and Midsummers Eve in June to St Lucia on 13th December. These are often marked with a specific food or dish. In fact, most Swedes even have a designated name day when you can expect a few cards and a slice of cake in honour of your name. Sometimes we celebrate food itself National Cinnamon Bun Day on 4th October must surely be one of the best days of the year.

A knowledge of what is in season is deeply engrained in every Swede from an early age. Ever since I was old enough to walk, I was taught to pick ingredients (often from the wild) and recognize when they were ripe and ready. I grew up foraging for berries and whiling away afternoons fishing. We gathered bilberries, raspberries and dainty, perfumed wild strawberries in the late summer. In the spring, donning gardening gloves for protection, I snipped young nettles for soup, dandelion leaves for salads and plucked clove flowers, just to suck out the sweet nectar from the petals.

I grew up thinking that all this was part and parcel of life. For me, food became heavily associated with different times of the year and steeped in ritual. Id gut herring with my mum before Midsummers Eve, staying up late into the bright night to complete the task. In August I would steal one or, depending on how brazen I was feeling, two live crayfish from the crate for our annual crayfish party. I thought I was doing nature a good turn by setting them free in the sea. It wasnt until much later that I realized that releasing freshwater crayfish into the Baltic probably did them more harm than good.