Contents

Page List

Guide

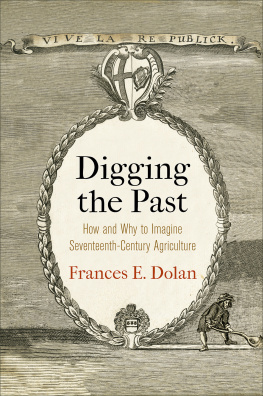

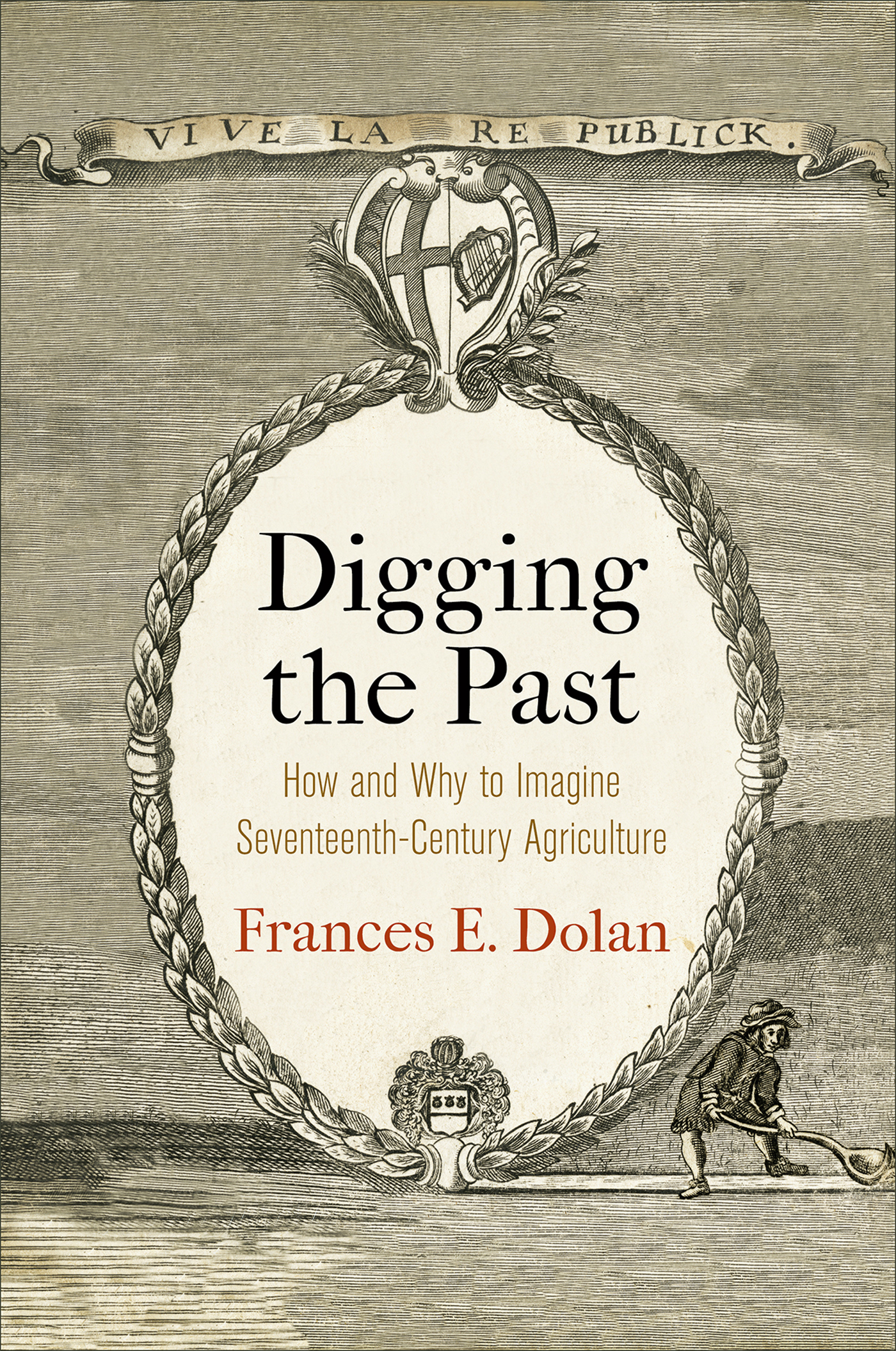

Digging the Past

Digging the Past

How and Why to Imagine Seventeenth-Century Agriculture

Frances E. Dolan

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

HANEY FOUNDATION SERIES

A volume in the Haney Foundation Series, established in 1961 with the generous support of Dr. John Louis Haney

Copyright 2020 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

13579108642

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Dolan, Frances E. (Frances Elizabeth), 1960 author.

Title: Digging the past : how and why to imagine seventeenth-century agriculture / Frances E. Dolan.

Other titles: Haney Foundation series.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2020] | Series: Haney Foundation series | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019046235 | ISBN 9780812252330 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Pastoral literature, EnglishHistory and criticism. | Agriculture in literature. | English literatureEarly modern, 15001700History and criticism. | AgricultureEnglandHistory17th century. | Agricultural innovationsHistory17th century.

Classification: LCC PR428.P36 D65 2020 | DDC 820.9/321734dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019046235

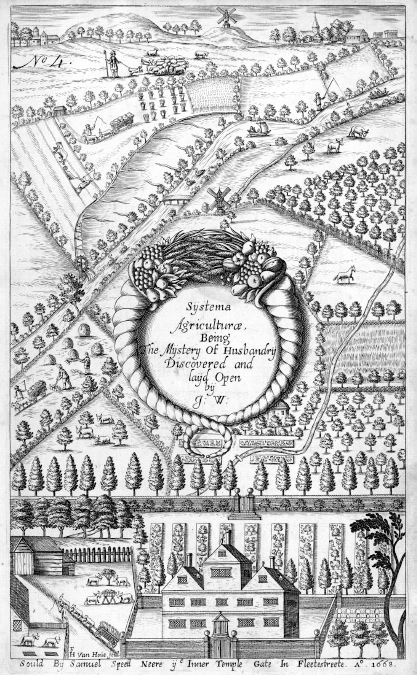

Frontispiece: Title page of John Worlidge, Systema Agriculturae (1668). Reproduced by permission of the University of California, Davis, Special Collections Library.

Contents

Note on the Text

In this book, I have chosen to modernize spelling and punctuation in all quotations and titles. This is true of quotations from both older and more recent works. For example, I spell plow consistently across quotations, even when quoting from British scholars who originally wrote plough. In verse passages, I use my judgment, leaving tumbleth rather than changing it to tumbles if rhyme and rhythm require. Although I modernize titles in the body of the text, in the notes titles appear as spelled in the Early English Books Online and the English Short Title Catalogue, so as to facilitate searching. As a consequence, the title of a work may look a little different in the text from the way it looks in a note. Searching for a model of modernizing in a work that also attends to history, I returned to Richard Helgersons practice in Forms of Nationhood (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992). I have also attempted to limit notes to one per paragraph although I have left a note at the end or near the end of any block quotations.

References to the OED are to the online edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. All parenthetical citations of Shakespeare plays are from The Norton Shakespeare, 3rd ed., ed. Stephen Greenblatt, Walter Cohen, Suzanne Gossett, Jean E. Howard, Katharine Eisaman Maus, and Gordon McMullan (New York: W. W. Norton, 2016), unless otherwise indicated. In , for example, I rely on the newest Arden edition of Titus Andronicus in my extended discussion of that play. I use The Complete Poetical Works of John Milton, ed. Douglas Bush (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), and all scriptural citations refer to The Bible: Authorized King James Version, with an introduction and notes by Robert Carroll and Stephen Pricket (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997). In modernized quotations, I have retained the spelling divers to signal the distinctly early modern meaning of several different or many.

Introduction

Critics of the global farming and food systems contend that we need to change how we produce and distribute food. If we dont, we will not be able to keep up with a warming planet and a growing population. If we do, we might be able to address pressing environmental issues, such as erosion, pollution, and climate change, as well as urgent social justice issues, including global food safety and security. Proposals to radically change farming in the industrial world are variously called regenerative or conservation agriculture or agroecology. Reformers motto might be Same Farms No Future, on the model of No Farms No Food, the slogan of the American Farmland Trust, which works to preserve farmland from development. Farming has to change, they argue, and change dramatically, if we are to have a future at all. But what is the role of the past in these fights for farmings future?

That question might seem irrelevant. The practical problems are so urgent that it might seem a waste of precious time to look backward; ignorance and disregard for history are so pervasive that it can seem hopeless to convince anyone to care about what has already happened. In her magisterial history Alternative Agriculture from the Black Death to the Present Day, first published in 1997, Joan Thirsk laments that, unfortunately, the decision-makers hoping to solve present-day problems generally have little or no historical parallels with which to set the present picture in perspective. Decades later, the problems are more pressing and those historical parallels more remote. And yet, many farmers, cooks, artisanal producers, and activists themselves evoke the past as a source of wisdom and inspiration. Often, they tell a story of decline in which our ancestors knew everything that mattered and now we must rediscover and reclaim what Darina Allen calls forgotten skills and Alexander Langlands calls lost knowledge. As Nina Planck puts it in Real Food: What to Eat and Why, real foods are oldthey are foods humans have been eating for thousands of yearsand they are traditional because they have been produced and prepared the old fashioned way, not out of mere nostalgia but because they are more flavorful and more nutritious than industrial or fake foods. If your grandmother ate it, then it must be real. Perhaps the most extreme, and currently the most popular, version of this logic is the paleo diet, with its attempts to recapture ancestral health. The great thing about this way of eating is that it tends to involve a lot of fat. But it is worth questioning so simple a reversal, by which regress becomes progress. As Raymond Williams argues, such accounts of the past often sentimentalize or even invent it. Williams finds in depictions of the golden age in Renaissance literature a myth functioning as a memory. Writers conjure up a happier past, Williams contends, in order to justify and authorize their vision of a better future. The happier past was almost desperately insisted upon, but as an impulse to change rather than to ratify the actual inheritance.