Introduction

When youre married, you want to kill your spouse. When youre single, you want to kill your self. Better her than me.

Chris Rock, Never Scared

So you got yourself a partner. Ive got a wife. Not exactly a partner. More like a rival. A rivalry. I wish I could say this is my partner.

Larry David, Mels Offer, Curb Your Enthusiasm

Today, marriage is celebrated as the bedrock on which the rest of society builds. For instance, in his 2004 State of the Union Address, President George W. Bush described marriage as one of the most fundamental, enduring institutions of our civilization.

What do we even mean by marriage? While debate usually focuses on who can or should marry, the most basic question remains: what does it mean to be married? This question resonates on two levels. First, what or who determines that one is married? Second, what are the consequences of being identified as married? One way of thinking about consequences is to focus on the rights, privileges, and responsibilities attached to being married. For the purposes of this study, I am most interested in assumptions about what kind of relation marriage imposes, enables, or sanctions between spouses. Our definitions of this fundamental institution are contradictory. On the one hand, marriage is defined as a loving, erotic bond between two equal individuals. On the other hand, it is construed as a hierarchy in which someone, usually the husband, has to be the boss. Marriage is celebrated as the melding of two into one and as a contract between two autonomous parties. While some see the present conflict among different models of marriage as constituting an unprecedented crisis, I will argue that this conflict between incompatible models and irreconcilable expectations is the history of marriage. It is thus a manifestation of continuity rather than rupture.

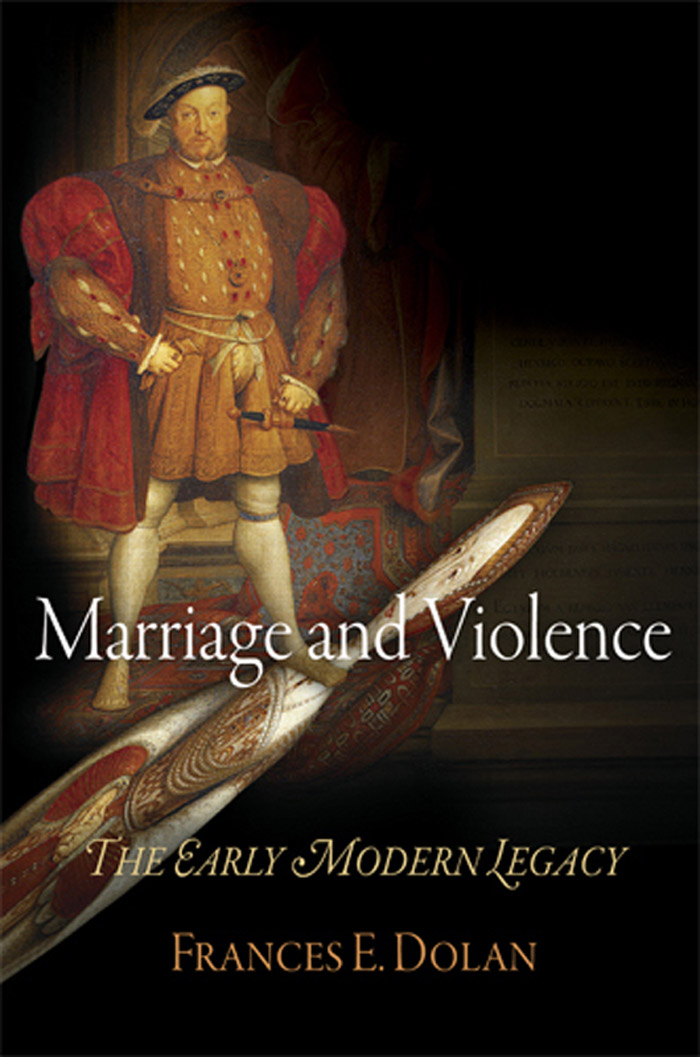

Some would trace the history of marital conflict as far back as cave dwellers. While the institution of marriage does have deep, tangled roots, I focus on our debts to one particular cultural tradition, arguing that we have inherited three models of marriage from early modern England (15501700): marriage as hierarchy, as fusion, and as contract. These three models are incompatible and, to make matters worse, each is riddled with internal contradictions. Each can be understood as promoting love between spouses and fulfillment for each or as subordinating one to the interests of the other. In early modern England, a radically visionary model of marriage as a loving partnership between equals flourished in part because of the Protestant Reformation. While this ideal was not wholly new, it first found stable institutionalization, full articulation, and broad dissemination in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Its promise remains unfulfilled because it never replaced a model of marriage as a hierarchy in which the husband must take the lead and the wife must obey; it also drew on the erotic and emotional appeal of a vision of marriage as the fusion of two into one without resolving the practical problems that vision obscures. Working with traditions that were already fractured and contradictory, then, the early modern period added new, equally vexed expectations for marriage. The emergent model of marriage as a contract seems to correspond to and ensure a partnership between equals; yet, as we will see, it did not escape or resolve presumptions about the unequal status of the parties to the marriage contract. Furthermore, the notion of spouses as contracting parties, each of whom acts out of self-interest, coexists uneasily with the ideal of marriage as a near mystical fusion in which one loses oneself. Each model proposes to explain the relationship between spouses. Yet, for all of the supposedly new emphasis on spouses as companions and partners, early modern religious, legal, and popular discourses reveal a deep distrust of equality. Associating equality with conflict, they suggest that once spouses confront one another as equals only one can win the resulting battles. Conflict can only be evaded or resolved by privileging one spouse at the expense of the other. Thus the ultimate message is that marriage only has room for one. The question then becomes: which one?

The Marital Economy of Scarcity

We can see this most clearly in three common figures for marriage. These figures do not correspond precisely to the three models of marriage I have outlined above. Rather, they attempt, unsuccessfully, to finesse the contradictions within and among those dominant models of marriage. The first is the figuration of Christian marriage as the creation of one flesh, which at once powerfully expresses theological, emotional, and erotic union and upholds an impossible ideal. Within Christian marriage advice, the pervasive insistence that the husband stands as the head of the marital body readmits a hierarchy between the spouses into the vision of marital union. Second, the common law offered a parallel formulation, suggesting that, through a legal fiction called coverture, husband and wife should become one legal agent by means of the husbands subsumption of his wife into himself. While common law did not wholly define married womens legal status, the fiction that husband and wife achieved unity of person had wide-ranging influence in the early modern period and beyond. Finally, a comic tradition, including plays, ballads, and jokes, would seem to mark an advance toward imagining spouses as separate and equal, since it assigns husband and wife similar claims on wit, desire, authority, and material resources. Yet it depicts this equality as a source of conflict because it compels husband and wife to war for mastery within their marriage and household, mastery figured as a single pair of pants only one can wear.

The conceptual similarity underpinning these familiar figures only stands out when one compares all three, as my study is the first to do. Taken together, the scriptural figure of one flesh, the legal fiction of unity of person, and popular debates about who wears the pants all suggest that marriage is an economy of scarcity in which there is only room for one full person.to resolve the problem of two fractious persons within the union of marriage. This definitive violence can take the form of spiritual struggles for salvation or damnation, battering and murder, or taming. In each chapter of my book, I show how the early modern apprehension of marriage as an economy of scarcity haunts the present as a conceptual structure or plot that concentrates entitlements and capacities in one spouse, and achieves resolution only when that spouse absorbs, subordinates, or eliminates the other.