T his Book has been in the works for a number of years, and a number of people were fundamental to its completion. First, I am indebted to Dr. Kathryn McPherson, a brilliant teacher who generously shared her invaluable wisdom and insight about feminist writing. From the very beginning, Kate has championed my work, and she has been a great source of inspiration and encouragement, especially through difficult times. I am also thankful for the financial support I received from the Graduate Program in Gender, Feminist & Womens Studies at York University and the Faculty of Animation, Arts and Design at Sheridan College, which enabled me to travel to conferences where I presented aspects of this book. I am also very indebted to editors Yoram Allon and Ryan Groendyk of Wallflower, who took a leap of faith with this project, which I will never forget. And finally, I wish to say a mammoth thank-you to Lou Mersereau, my partner in life and father to our two lovely and supportive daughters, Teresa and Louisa. Having read countless drafts, Lou has been a steadfast source of strength, patience, and encouragement. This book is dedicated to Lou, Louisa, and Teresa.

The myths governing the cinema are no different from those governing other cultural products: they relate to a standard value system informing all cultural systems in a given society. It is possible to use icons (i.e. conventional configurations) in the face of and against mythology usually associated with them .

Claire Johnston

I think we need to do more than try to document history. I think we need to probe. We need to have the freedom to romanticize history, to say, what if, to use history in a speculative way and create speculative fiction. I think we need to feel free to do that.

Julie Dash

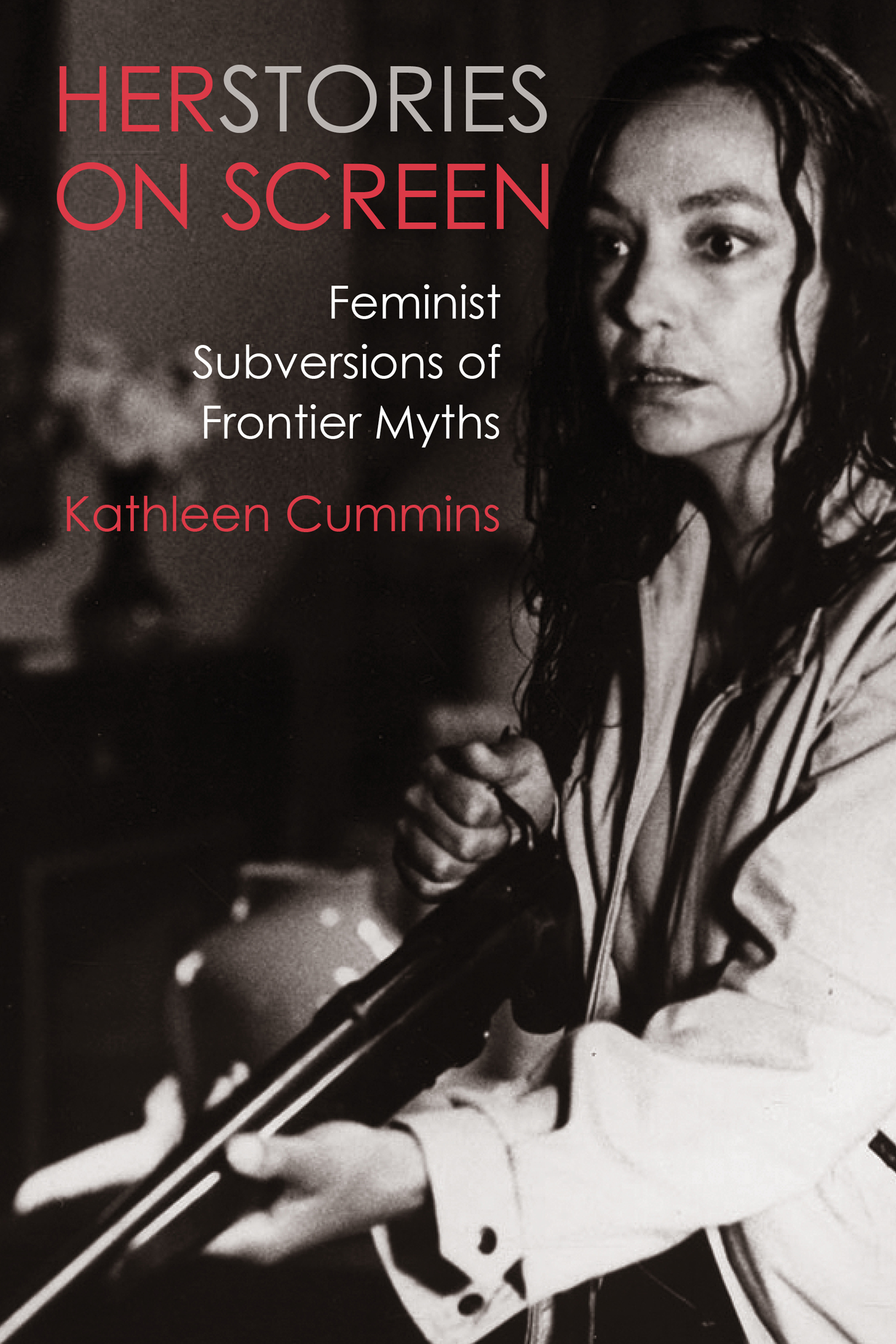

H erstories on Screen: Feminist Subversions of Frontier Myths is a transnational qualitative study that examines ten long-form dramatic narrative English-language films directed by women, produced between 1979 and 1993. These films tell stories of female emancipation and resistance in former white-settler nationsCanada, the United States, New Zealand/Aotearoa, and Australia. Set in rural landscapes that represent or evoke iconic national frontier spaces, the films take place across a wide temporal range, from the mid-nineteenth century to the late twentieth-century. Though a few of these films are set in contemporary times, all of them aim to subvert tropes strongly associated with frontier myth-histories (e.g., the Western) and hence challenge dominant narratives that have rendered invisible and irrelevant the voices, experiences, and stories of women across the axes of race, sexuality, class, and age. Examined collectively, the films can be seen as representing a kind of transnational feminist film wave in which women filmmakers told herstories on the big screen. The term herstory is apt for this study because the issues and discourses that permeate these films reflect the key debates that animated what is commonly referred to as second-wave feminism or the womens movement of the 1960s and 70s. An expansion of the fight for suffrage waged by first-wave feminists of the late nineteenth century, the often oversimplified second-wave womens movement comprised a diverse range of struggles focalized on gender equity, reproductive rights, the nature of gender, and the role of the family. Born out of the second wave, the herstory term means history considered or presented from a feminist viewpoint or with special attention to the experience of women.

contains detailed plot synopses.

The scope of this study is defined by the following factors. First, the study focuses specifically on films that were directed by women. Second, the films all hail from former frontier white-settler nations and are all in the English language. Third, all the films are narrative feature films with the intent to reach a large audience. Fourth, the selected ten films are all deemed landmark feminist texts and represent significant watershed moments in womens cinema. Finally, all the selected films deploy or subvert (or both) tropes of popular frontier myth-history narratives.

TABLE I.1 The Films |

Country | Film Title | Director | Year of Release |

Australia | My Brilliant Career | Gillian Armstrong | 1979 |

Bedevil | Tracey Moffatt | 1993 |

Canada | My American Cousin | Sandy Wilson | 1985 |

Loyalties | Anne Wheeler | 1987 |

The Wake | Norma Bailey | 1986 |

New Zealand/Aotearoa | Mauri | Merata Mita | 1988 |

The Piano | Jane Campion | 1993 |

United States | Daughters of the Dust | Julie Dash | 1991 |

Thousand Pieces of Gold | Nancy Kelly | 1991 |

The Ballad of Little Jo | Maggie Greenwald | 1993 |

Source: Authors own data. |

LA POLITIQUE DES (FEMME) AUTEURS

The focus on women directors is rooted in a historical critical tradition in which authorship of a film has been largely attributed to the director rather than to other key contributors such as the producer or screenwriter. The concept of the director as author has been around since the 1920s, but it became entrenched in film criticism largely through the French film journal