Contents

Guide

Contents

How to use this ebook

Select one of the chapters from the and you will be taken straight to that chapter.

Look out for linked text (which is underlined and in blue) throughout the ebook that you can select to help you navigate between related sections.

You can double tap images to increase their size. To return to the original view, just tap the cross in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

Introduction

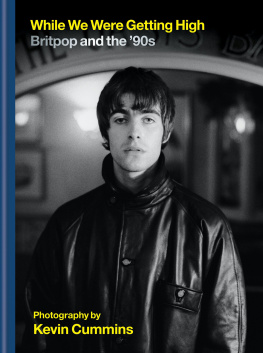

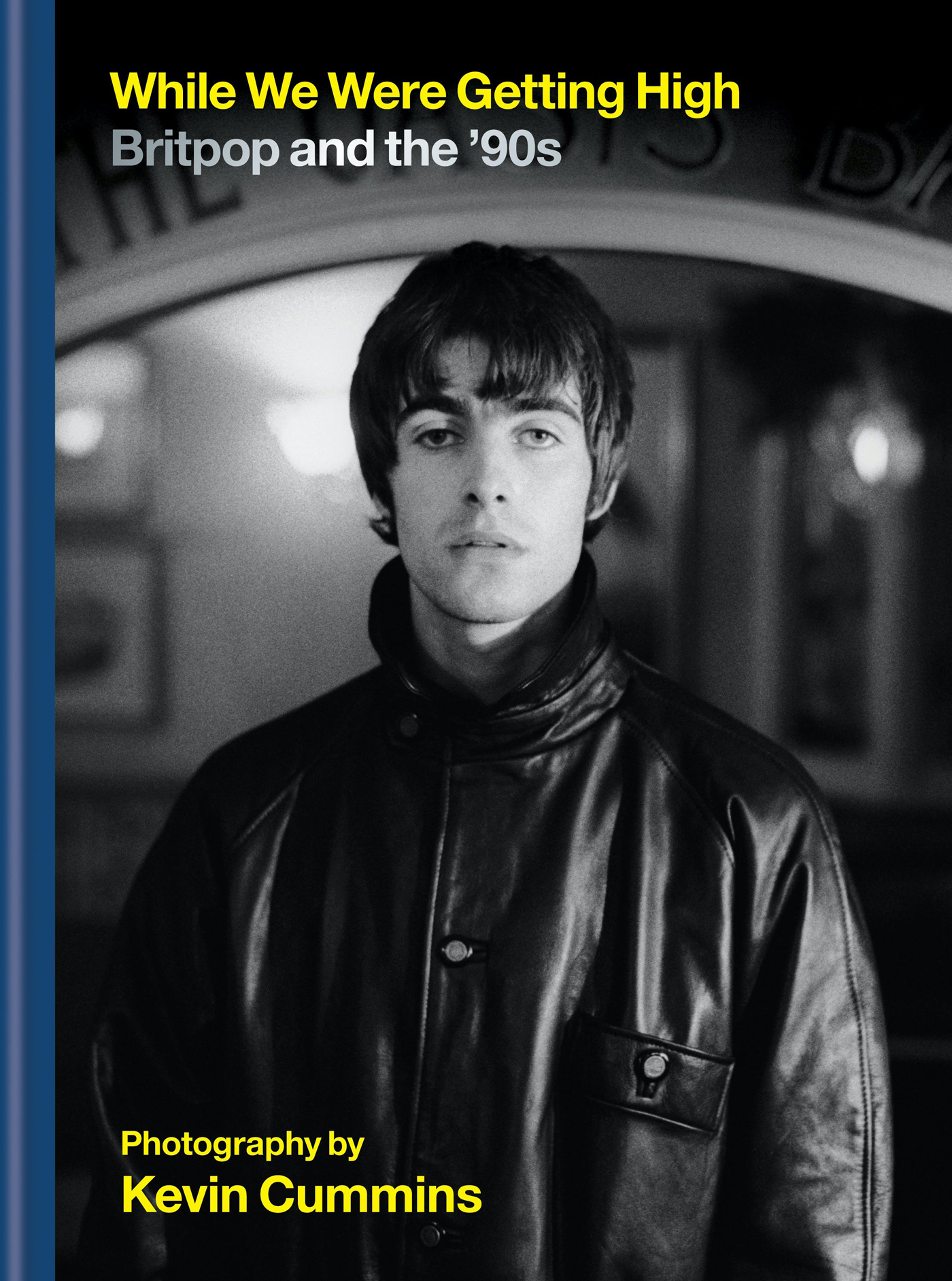

Kevin Cummins

On 15 July 1961, the Daily Telegraphpublished a jazz feature by Philip Larkin under the header Cool, Britannia. The comma here is crucial.

Just over 35 years later, cool Britannia became one of those meaningless expressions beloved by ad execs who thought it defined the zeitgeist but more importantly, they thought it defined them. In the mid-1990s anything and everything British was cool. Celebrity mockney chefs: cool. Lads mags: cool. Tony Blair: cool. The Spice Girls: cool. Ladettes: cool. New Labour: cool. Except none of it was cool. It was just another way of marketing a certain type of Britishness to the masses. Britpop was a term I was uncomfortable with, and I wasnt alone.

In April 1993 Selectmagazine dropped a photo of Brett Anderson over a backdrop of a Union Flag, using the coverline: Yanks Go Home! Suede, St Etienne, Denim, Pulp, The Auteurs and the Battle for Britain. They were reducing the standard of the once lofty music press to the level of red-top, flag-waving patriotism.

Brett was furious. His songs were documenting the world around him, illustrating its cheapness and failure, not about Britishness in all its perceived glory. Suddenly Britpop became a movement and flag waving became the norm. Newspapers and magazines love a catch-all expression, and thus the term Britpop was born.

Most British bands distanced themselves from the term, but they were fighting a losing battle. All the UK bands we featured in NMEover a period of three to four years would be asked about their Britishness. They werent asked about the elements of toxic masculinity, misogyny and racism that many commentators and musicians were uncomfortable with. If any publication defined the zeitgeist it was Loaded. Theyd championed the birds, booze, football, clubbing and casual drug use culture from issue one in May 1994. Uncool Britpop was designed for them; for men who should know better. And so it went on

At NME, I like to think we distanced ourselves from the more laddish end of the spectrum. We concentrated on the musicians and their music, and some great music came out of this period. I wanted to shoot serious portraiture and consequently I felt we gave the bands the gravitas they deserved. Of course, it was difficult to do this when commissioned to shoot an on-the-road piece with Oasis it was hard enough to stay alive. Similarly with Blur. Both bands lived life to excess. It was exhausting but a lot of fun, too.

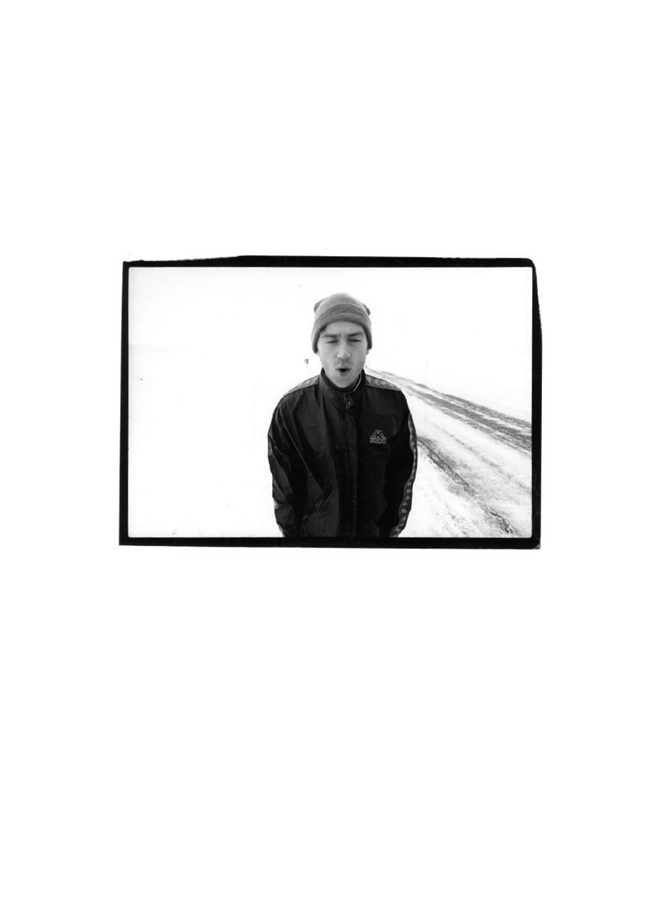

I usually define my job as 10 per cent photography and 90 per cent hanging around hotel lobbies waiting for the band to turn up. Its kind of ironic that the was taken while I was sitting in a hotel lobby in Newport, Gwent, and when he eventually turned up he was perfectly framed by the door with The Oasis Bar sign above his head.

Twenty-five years on and its difficult to separate Britpop from todays political climate. The symbolism of the Union Flag is more loaded and exclusivist than ever. Was Britpop a precursor to the Brexit mentality? Its hard to truly know, though I suspect a connection somewhere along the way. I am delighted that four very different protagonists of the era Noel Gallagher, Brett Anderson, Sonya Aurora Madan and Martin Rossiter answered my questions about Britpop and its legacy, openly, honestly, and with insight.