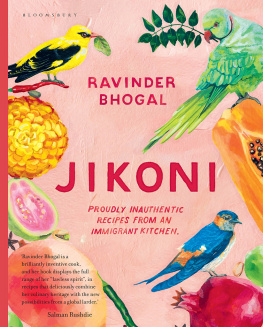

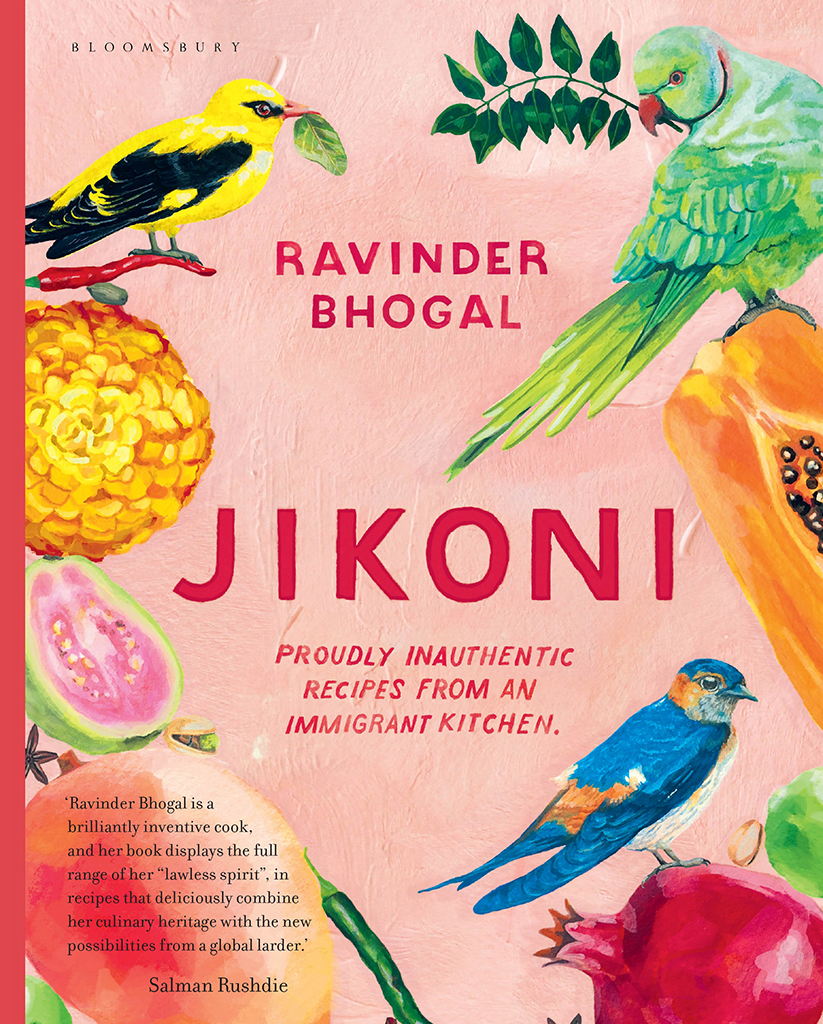

Ravinder Bhogal - Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen

Here you can read online Ravinder Bhogal - Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Jikoni

means kitchen in Kiswahili,

the spirited language spoken in Kenya, the country where I was born. I grew up in Nairobi, in a whitewashed house built by my bhaji (grandfather). Like many Indians before him, he left his native Punjab in the 1940s in search of work. Most of them worked as labourers building the railways lines of neat-as-needlework stitches across wild terrain to link Kenya with Uganda. Many later settled in Uganda, only to be expelled in the 1970s under the bloody regime of Idi Amin. Bhaji spent much of his time constructing properties in Kenya, but he also spent a great deal of it

falling in love with the red-earthed, blossoming landscape

of this tropical East African clime, so much so that he decided to lay down roots.

Our family was neither small nor quiet there were six just in my nuclear clan, but the tradition of living with extended relations meant that there was anywhere between fifteen and twenty-five people in our house at any one time a source of both cosiness and chaos. Mealtimes for a tribe that never seemed to stop breeding had to be handled with military precision, and every woman and girl was recruited to the cause, willingly or otherwise.

I was a reluctant assistant to my mother, who had a stern approach to all domestic duties. Taking pity on me, my grandfather would let me hop onto his strong broad shoulders, and take me off for a weekly treat. We would drive into town in his rickety Volkswagen and head straight for Sno Cream, a kitsch ice-cream parlour where gelatos like dreamy sherbet- hued clouds came in cut-glass dishes. It was over our love of the naughty-but-nice stuff that we bonded, and I think this was where my association of food with pleasure began. One day, in the season of the long rains,

when the garden bloomed madly and insects seemed to congregate

in every corner of it, bhaji bought me a little aluminium stove that could actually be lit with crumpled-up newspaper. I took to making towers of chapattis that were singed and bitter, but he would praise and encourage me, eating them with relish. This made me realise that feeding someone made love expand, and so I decided to embrace my kitchen duties.

After that I spent most of my time making a nuisance of myself, squeezed into a small jikoni full of women confidently throwing a series of fragrant seeds and pods into pots, gossiping in a unique patois made up of several inherited tongues including Swahili, Punjabi, Gujarati, Urdu, Hindi and English.

This was also my initiation into the secret language of cooks

where recipes were never recorded in ink on paper, but sung down the generations like feminine gospels, until every daughter knew them off by heart. It was here that I felt truly alive, my every sense awake to the subtleties of the kitchen: the cheery whistle of a pressure cooker; the cloud of steam rising from an ochre broth gilded with turmeric, its sweet, sour, hot, salty and deeply, deeply spicy flavours all expertly balanced. My nose was acutely attuned to the potency of each spice my mother crushed in her crude stone pestle and mortar. Everything was safe. Everything was familiar.

When I was seven, we made an abrupt voyage to England. Our usual trips to visit family in London had always been a merry-go-round of Fortnum & Mason, Hamleys and shiny biscuit tins, but after several weeks of living in a frigidly cold flat above a shambolic shop that was very much in need of a womans touch, it became clear that this trip was different, and we were not going back.

Homesickness was an ordeal I found difficult to shake off. I felt displaced and alienated, bullied at school for my foreign accent and NHS specs. I existed in a strange sort of suspended animation, carrying the burden of living between two worlds. I had been accustomed to creepers, colossal jamun trees and rugged, open terrain my new landscape was barren, the horizon heavy with haggard buildings set against a terrifying Milky Way of artificial lights. I longed for the familiar, and for the foods that signified the familiar for me.

I developed a sensual nostalgia for the smell of wet, red Kenyan earth,

for the scent of guavas warming on the trees in the garden.

I cant remember exactly how long it took me to settle and even when I did, the dream of returning endured. Nostalgia makes the things you hastily leave behind feel more precious than ever: the favourite dolls, the language, the neat and beloved grandmother, the culture. But for me it was the distinctive taste and smell of home I missed the most. Eventually, the hole in my stomach and soul led me into our modest English kitchen with my mother, where we learnt to merge our old and new worlds. We occupied a hinterland where we fused new ingredients with our old traditions, unwittingly creating a new cuisine.

Our recipes displayed a rebellious spirit

lawless concoctions that drew their influences from one nation and then another. We took the traditions of our ancestors and their regional home cooking and overlaid them with the reality of our new home and whatever its various food markets, delis, canteens and multicultural supermarkets had to offer on any given day. This is what I suppose could be loosely termed immigrant cuisine,

proudly inauthentic recipes that span geography, ethnicity and history.

It was in the kitchen that I found my sanctuary and made peace with my new nation. As I grew up and graduated to cooking alone, unaided by my mother, I realised that a kitchen might provide a little bout of perfection, disappearance and luxury, amid the stresses of constantly trying to fit in. I relished every opportunity to cook and, more importantly, to feed, quickly identifying that the happy stability of mealtimes from breakfast to the very last titbit before bedtime was just the tonic for an uprooted family. Even now, a day punctuated by great meals still really matters to me.

You could say that it was cooking that liberated me. In fact having a kitchen of ones own could be considered, in the Virginia Woolf mode, a matter of personal freedom. Growing up in a patriarchal Punjabi family as daughter number four was at times stifling. I chafed at the constraints of what was permissible (embroidery, crochet, cooking for family, the oompah of the creaking harmonium at prayer ceremonies) and what was verboten (discos, climbing trees, boys, and dreaming of cooking for anyone other than your future husband and children).

Cooking is a highly skilled and often selfless endeavour, especially when it is women who are doing the feeding. As I watched my grandmother, mother, aunts and sisters join the cult of domesticity, I felt restless, and inwardly rebelled at the drudgery of it all. At the same time, I found solace in cookery books and cookery shows powerful female role models like Madhur Jaffrey and Nigella Lawson gave me the faith that cookery could be a career prospect, rather than just a feminine duty.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

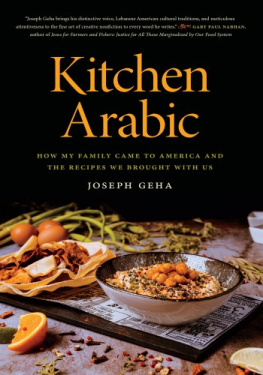

Similar books «Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen»

Look at similar books to Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Jikoni: Proudly Inauthentic Recipes from an Immigrant Kitchen and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.