BOOKS BY KAY S. I-IYMOWITZ

KAY S. HYMOWITZ

To my parents, Leon and Emily Sunstein, who know a thing or two about marriage

I WANT T o THANK both the William E. Simon Foundation and the Randolph Foundation, which generously provided funding for my work at City Journal. Brian Anderson was an enormous help in updating the essays and shaping them into a coherent argument. Myron Magnet was, as usual, a wonderful combination of delighted booster and demanding taskmaster. At the Manhattan Institute, Larry Mone, Lindsay Young Craig, Clarice Smith, Ed Craig, Ben Plotin- sky, David DesRosiers, and Molly Harsh provided much needed support.

I owe a great debt to Peter Cove who came to me with an idea for a book about "missing men" several _years ago. This book is not the one Peter had in mind or that I ever expected to write, but his idea inspired much of my recent work for City Journal and helped bring some of my previously published articles into a new light. Thanks also to Lee Bowes, Jan Rosenthal, Fred Siegel, Larry Mead, Ron Haskins, Sara McLanahan, Andrea Kane, Sara Brown, and Emily Flint. By giving me the opportunity to review relevant books that might otherwise have escaped my attention, and by insisting that I carefully recount the arguments of those books, the guys at Commentary-Gary Rosen, Neil Kozodoy, and Gabe Schoenfeld-unwittingly aided and abetted these essays. I am grateful to the many researchers too numerous to mention here who took the time to explain their work to me; I thank them also for declining to comment on my obvious innumeracy during those conversations. I also want to thank the men and women I probed about marriage and parenthood at America Works, in hospitals, in postnatal clinics, and, even on occasion, on the streets of Brooklyn.

Thanks, yet again, to my youngest child, Anna, who has reached the last year of suffering through my deadlines and obsessions as she heads off to college, and, of course, to my husband Paul Hymowitz, whose humor has lightened many loads.

K. S. H.

New York City

July 2006

vii

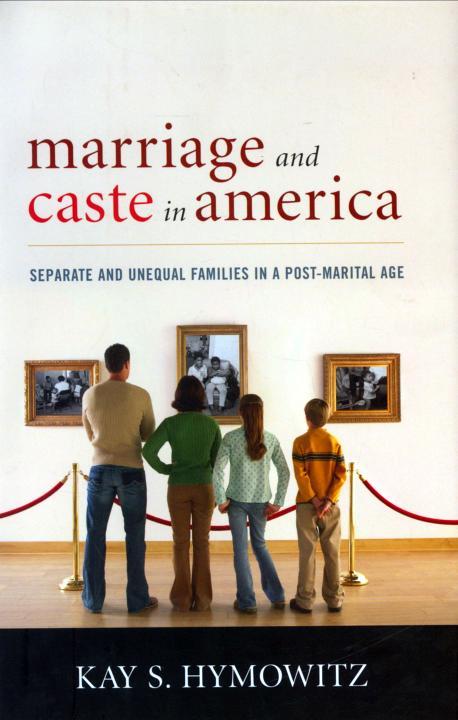

M Y ARGUMENT I N these essays can easily be summed up: the breakdown of marriage in the United States-which began about forty years ago as divorce and out-of-wedlock birthrates started to soar-threatens America's future. It is turning us into a nation of separate and unequal families.

Sounds overwrought? Bear with me, for I offer this bleak warning not out of religious conviction-I am an agnostic-nor out of any devotion to Eisenhower-era family life-I was around then and know better-nor because of a Hallmark tenderness for the institution-I've been married too long for that. I say it because it has become clear that family breakdown lies at the heart of our nation's most obstinate social problems, especially poverty and inequality. To put it more broadly, there is no way to attack these worrisome economic trends without tackling culture-the system of beliefs, values, and practices that help us define and live a good life.

Most people assume that divorce, unmarried motherhood, fatherlessness, and custody battles are all equalopportunity domestic misfortunes, affecting the denizens of West Virginia trailer parks or Bronx housing projects just as they do those of Malibu beach homes or Park Avenue co-ops. It's understandable that this conviction is widespread; the media loves stories of celebrities and billionaires gone wild. Nevertheless, as I explain in detail in the title essay to this book, the assumption that Americans are all in the same boat when it comes to marriage collapse is dead wrong.

There is a typical single mother, and she is not Murphy Brown or Angelina Jolie. (It's necessary to begin by talking about mothers because in the vast majority of cases it is women who have custody of their children.) She is poor, or near poor. She has no college degree. She has few of the skills essential for negotiating a tough new economy. On the other side of the tracks is her college-educated counterpart. She is skilled, of course. She is also married. Nov add this fact to the mix: children of single mothers are less successful on just about every measure than children growing up with their married parents regardless of their income, race, or education levels: they are more prone to drug and alcohol abuse, to crime, and to school failure; they are less likely to graduate from college; they are more likely to have children at a young age, and more likely to do so when they are unmarried. Put the two trends together-more marriage among the better educated, on the one hand, and diminished prospects for the children of single mothers on the other-and you get double trouble for the country's most vulnerable: poor or working-class single mothers with little education having children who will grow up to be lowincome single mothers and fathers with little education who will have children who will become low-income single parents-and so forth. Meanwhile college-educated, middleclass married mothers are raising children who go to college, get married, and only then have children-who will grow up and go to college, get married, and so on. A selfperpetuating single-mother proletariat on the one hand, and a self-perpetuating, comfortable middle class on the other. Not exactly what America should look like, is it?

At this point, inquiring minds want to know the answers to several questions. Why are low-income mothers not getting hitched before they have kids while middle-class women are? And why does marriage make such a big difference to children-and to their future status-anyway? Is it just that two parents mean more "economic and social inputs," as social scientists might put it?

The answer to the latter question is a categorical no, and to understand why, we need to step back for a moment and think about what marriage is. Marriage exists in every known society, no matter how poor or rich; it is what social scientists call a "human universal." But marriage, it is obvious, also comes in various shapes and sizes. That is, in addition to being a universal, it is also a cultural institution with specific cultural meanings that have been shaped by local history, economy, religion, and social ideals. American marriage is no exception.