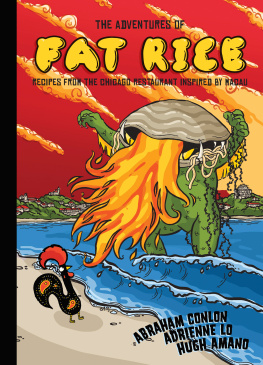

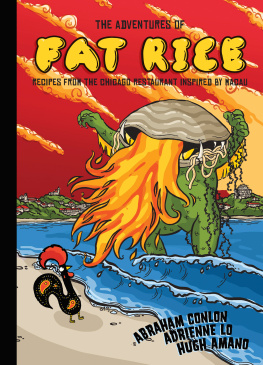

Copyright 2016 by Abraham Conlon and Adrienne Lo

Photographs copyright 2016 by Dan Goldberg

Illustrations copyright 2016 by Sarah Becan

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ten Speed Press,

an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group,

a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

www.tenspeed.com

Ten Speed Press and the Ten Speed Press colophon are

registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Conlon, Abraham, author. | Lo, Adrienne,

1983-author. | Amano, Hugh, author.

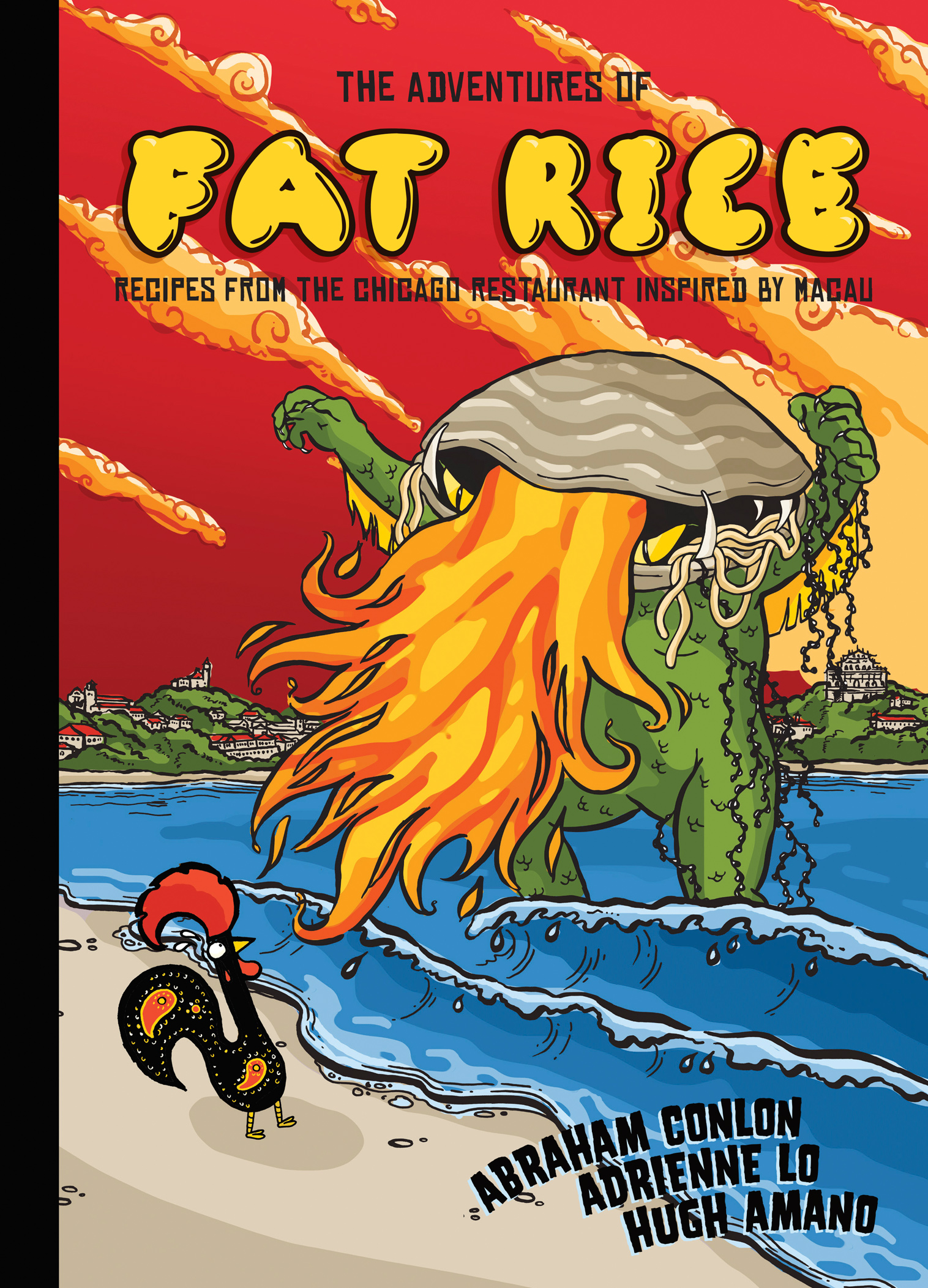

Title: The adventures of Fat Rice : recipes from the

Chicago restaurant inspired by Macau / Abraham Conlon,

Adrienne Lo, and Hugh Amano.

Description: Berkeley : Ten Speed Press, [2016]

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016014121 (print) | LCCN 2016019155 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, ChineseMacanese style.

Fat Rice (Restaurant) | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX724.5.C5 C66 2016 (print)

LCC TX724.5.C5 (ebook) | DDC 641.595dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016014121

ISBN9781607748953

Ebook ISBN9781607748960

v4.1

prh

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

MACAU, 2011

Far away from Chicago, across the Pearl River estuary from Hong Kong, we are standing in front of the most iconic symbol of Macau. The massive stone faade and a few ruins are all that remain of St. Pauls Church, an enormous Portuguese cathedral designed in the late 1500s by the Italian Jesuit Carlos Spinola. The images carved into the stone of the last remaining wall are rich with East-meets-West symbolism: the Virgin Mary as the Apocalyptic Woman, standing on top of a seven-headed hydra with a description of the scene written in Chinese characters; sculptures of the founders of the Jesuit order alongside the playful faces of Chinese lions; a bronze statue of Jesus beside a golden chrysanthemum (a Japanese sun symbol), reflecting the influence of the exiled Japanese-Christian sculptors responsible for the carvings.

After exploring the ruins, we make a quick jaunt to another place that reinforces the feeling of Macaus historic position as a crossroads between East and West (and makes mainland Chinese tourists feel like theyre in faraway Europe): the Fortalaza do Monte, built in 1624 as protection against Dutch invaders. The fortresss massive lower stone walls are scattered with a few windswept, withered buds and blossoms of a papaya tree. Known as fula papaia, these male flower buds used to be a staple in Macanese cooking, essential to dishes like crab with papaya flower (caranguelo fula-papaia) and stir-fried greens with shrimp paste and papaya flower (). But today, nearly all of the papaya trees that bear these beautiful, slightly bitter buds are gone, along with the people who once cooked these traditional Macanese dishes. This is why we are here: to learn about and try to understand a cuisine that may soon be forgotten.

This was our first visit to Macau, but we had only allotted thirty-six hours for our culinary excursion. We had eaten the famous Portuguese egg tarts (pastis de nata), pork chop buns (zhu pa bao), grilled sardines, garlicky suckling pig (leitao), and curried everything, from chicken to oxtail to crabs, that Macau is known for. Wed caught a very brief glimpse of Macaus rich culinary historybut our trip was too short and we wanted more. Even after just thirty-six hours, we were hooked on the islands intermingling of Chinese, Portuguese, Indian, Malay, and African influences.

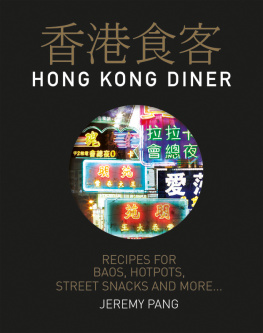

Macau was actually the last stop of a much longer journey for us. The week before, we had been in metropolitan Hong Kong, feasting on live seafood and simple Cantonese cuisine; before that, we had learned the techniques of the numbing and fiery (ma-la) dishes of Sichuan province at the Sichuan Institute of Higher Cuisine. We had embarked on this trip to learn more about the regional cuisines of China and to get inspiration for the series of underground dinners we were hosting back in Chicago. Since we were in the neighborhood, we knew we had to stop in Macau, but nothing could have prepared us for its eerie, fantastical mlange of cultures: towering, shiny casinos alongside drab, aging colonial architecture; fair-skinned Asians speaking Portuguese while eating brothy noodles with chopsticks, as well as mainland Chinese tourists eating baked spaghetti dishes with forks; olive oilrich bacalhau (Portuguese salt cod) on the same menu as steamed fish with ginger and scallion; the scent of curry and soy sauce mingling with that of freshly baked bread and strong coffee.

This is Macau today: a gambling mecca larger than Las Vegas, but formerly one of the worlds most thriving trading ports, with a history of cultural confluence dating back to the mid-1500s. In 2011, twelve years after Portugal handed it back over to China, Macau was still in a state of transition. Most Portuguese-speaking Macanese people, along with their multicultured, trilingual (English-Portuguese-Cantonese) offspring, had moved awayto Portugal, Canada, the United States, Brazilto be with their families or start new ones of their own.

We were due back in Hong Kong that evening and only had a few hours before we had to catch the ferry. So, with nothing but a Lonely Planet guide tattered map in hand (this was well before phones were as smart as they are today), we embarked on our last culinary adventure of the trip: a stop that would change our trajectory forever.

Okay, lets get outta here. Its already 1 p.m., and I think this place closes at 3. Lets go right up here on to Rua de Dom Belchior Carneiro.

We were looking for a specific restaurant that was located near the reservoir. The cobblestone streets, pastel buildings, and shops with Portuguese names like Fatima made us feel like we were a world apart from central China, despite the fact that Hong Kong is a mere hours ferry ride away.

After the Rotundo do Almirante Costa Cabral, this street will turn into Rua de Tomas Vieira. Whats up with these street names? Theyre all named after Portuguese guys. You think were on the right track?

The duality of the citypartly a product of the One Country, Two Systems principle of Chinas dealing with both socialism and capitalismis apparent, for even though the names of streets and storefronts are written in Portuguese, Chinese characters are not direct translations and often mean something completely different. Bus and taxi drivers dont recognize the streets by their Portuguese names; you have to know their Chinese names to get around. Dont get into a cab and expect that you can speak Portuguese because your Cantonese is rusty; take it from us, that