FOREWORD

by Chris Kelly, Producer

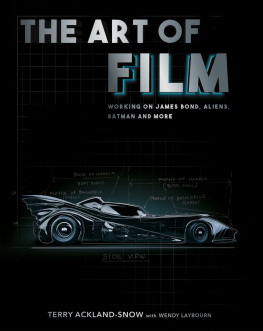

Invariably, media attention is focused on the stars, for obvious reasons. Its their faces that appear on posters, their names that, it is assumed, sell films and television programmes. However, for anyone with a genuine love of the business, the real heroes and heroines are the unsung ones; the problem-solvers, the imaginative engine room behind the visual experience. Chief among these are the Production Designers and Art Directors.

For decades, Terry Ackland-Snow has been among the best of British. As a producer, Ive had the good fortune to work with him on many occasions. Unflappable, resourceful, indefatigable, cheerful and loyal, he has been more than equal to every challenge weve thrown at him. Before the ubiquity of CGI, Terrys inventive skill enabled him to turn the most fanciful or demanding script into plausible visual reality; on time and on budget. Five words that are music to a producers ears.

It is typical of his generosity of spirit and love of his craft that, instead of hanging up his drawing board, he is devoting his considerable energies to passing on his secrets to a younger generation, the Oscar-winners of tomorrow. Typical too that despite the industrys increasing reliance on the computer, Terry continues to stress the fundamental importance of draughtsmanship. No one is better qualified to teach and inspire.

DEDICATION

In memory of my brother, Brian Ackland-Snow, 19402013

At the time of his death in 2013, my brother Brian hadnt worked for fourteen years due to the cruel illness, Alzheimers Disease. However, his humour, compassion and generosity still shone through. He was a very unselfish man in the workplace and as a husband and father.

Brian loved drawing, art and modelmaking from an early age, but, at our fathers insistence, he had to complete his carpentry apprenticeship with the family business before he started in design. After this, he joined the Art Department at the Danziger Studio in Elstree as an Art Department Assistant, subsequently working on his first film, The Road to Hong Kong, at Shepperton Studios, under Production Designer Roger K. Furse.

He went on to work on many films and television programmes from 1962 until he retired, having won an Oscar in 1987 for Best Art Direction and a BAFTA for Best Production Design for A Room with a View, and a Primetime Emmy for Outstanding Individual Achievement in Art Direction for the mini-series Scarlett.

Brians film and television credits include: Without a Clue; A Room with a View; Superman III; The Dark Crystal; McVicar; Dracula; Death on the Nile; Cross of Iron; The Slipper and the Rose; Theres a Girl in My Soup; Battle of Britain; 2001: A Space Odyssey; The Quiller Memorandum; The Road to Hong Kong; The Magnificent Amersons; Animal Farm; Kidnapped; Scarlett; Cadfael; The Man in the Brown Suit; Hart to Hart.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Within this book we acknowledge all who are sadly no longer with us, but who, through their outstanding innovations from the early days of film design to the present day, have left their legacy for the benefit of all filmmakers.

A very special thank you to Lauren Crockatt, Davina Harbord, Emma James, Miranda Keeble and Ciara Sheridan, whose dedication to the cause, combined with attention to detail, kept us focused throughout all the difficult times!

Special thanks to the following for their contributions: Andrew Proctor Art Department and Visual Effects; Terry Apsey Construction Manager; Dominic Ackland-Snow Construction Manager; Ken Barley Head of Department Plaster; Adrian Start Head of Department Paint; Darcey Crownshaw Set Decorator and Founder of Snow Business; Leigh Took Special Effects Supervisor and founder of Mattes and Miniatures Visual Effects; David Sproxton Animator and co-founder of Aardman Animations; Terry Bamber Production Manager and Assistant Director; Jamie Anderson Director of Anderson Entertainment; Dayne Cowan Visual Effects Supervisor; Robin Vidgeon Director of Photography; John Glen Director; Chris Kelly Producer; Peter Young Set Decorator; Tony Pratt Production Designer; Peter Murton Production Designer; Simon Murton Concept Artist; Harry Lange Production Designer; Carol Ackland-Snow Photography and Sketch Department; Bill Stallion Storyboard Artist, thanks to his family; Keith Ackland-Snow for providing information on the Ackland-Snow family; and Paul Isaacs for providing a selection of story boards included in the book.

Thanks to the following for illustrations: Warner Brothers Batmobile Photograph; Universal Studios; Henson Productions Muppet Storyboards; MGM James Bond Photographs; Disney Art Department photographs of The Dark Crystal and Labyrinth; EON photographs of James Bond, The Living Daylights; Columbia Pictures The Deep; 20th Century Fox The Rocky Horror Picture Show; Paramount Pictures EMI Death on the Nile; The Imaginarium.

Preface

By Wendy Laybourn

Wendy Laybourn.

What is illusion? The Collins English Dictionary defines it as a deceptive impression of reality. Nowhere is this definition so relevant as in film production. In order to transport the audience to wherever the script leads, the Art Department uses illusion to create whatever style is needed to produce the appropriate backdrop for the performers and the rest of the film crew to work with. If you read through the Film Crew Breakdown below, you will fully appreciate the number of people involved in any production and will better understand what a critical contribution the Art Department has in the finished film or television programme.

The film crew uses light, colour, sound and movement to transform the script into a drama, a musical, a flight of fantasy, or a blood-curdling horror movie. So never forget, as you become deeply involved in the latest tricks or technologies, that you are an entertainer first and foremost, putting images up on a screen for the enjoyment of an audience and following in the traditions set by the earliest filmmakers.

The creation of film technology was not originally meant for artistic expression, but began simply as a commercial extension of live theatrical events, recording them much like the modern documentary. The practitioners soon found that portraying a story on screen was quite different from that of a theatre production. There are major qualities available to filmmakers that are difficult, if not impossible, to achieve on stage. For example, the close-up of faces and objects in order to achieve emphasis was first used by D.W. Griffith in 1907. The ability to use the camera lens to zoom in and out of any particular aspect of a scene gives the Director, Designer and Cinematographer enormous scope to add depth and quality to the action.

The controlled use of sound over action and vice versa was first used in 1926 when it was found possible to link both sound and picture together on celluloid. In addition to giving the Director the ability to emphasize the dialogue, this technology gave rise to sound design and atmospherics, as well as a specifically written and arranged music track that augments the action and creates the style and feel of the film.

When film was in its infancy it was essentially just a series of animated photographs, but then the showmen stepped in to work with the photographers and began the process of what is now taken for granted as film production. However, the essence of filmmaking has not really changed since those early days and it is important to remember that the early filmmakers were working with very basic and unsophisticated equipment and materials. Nonetheless, the creativity of the entire crew and their passion for telling the story is the same as ever, it is just the technology that has grown over the decades so that the tricks and scenic illusions have become more and more exotic, making the seemingly impossible now a practical reality.

Next page