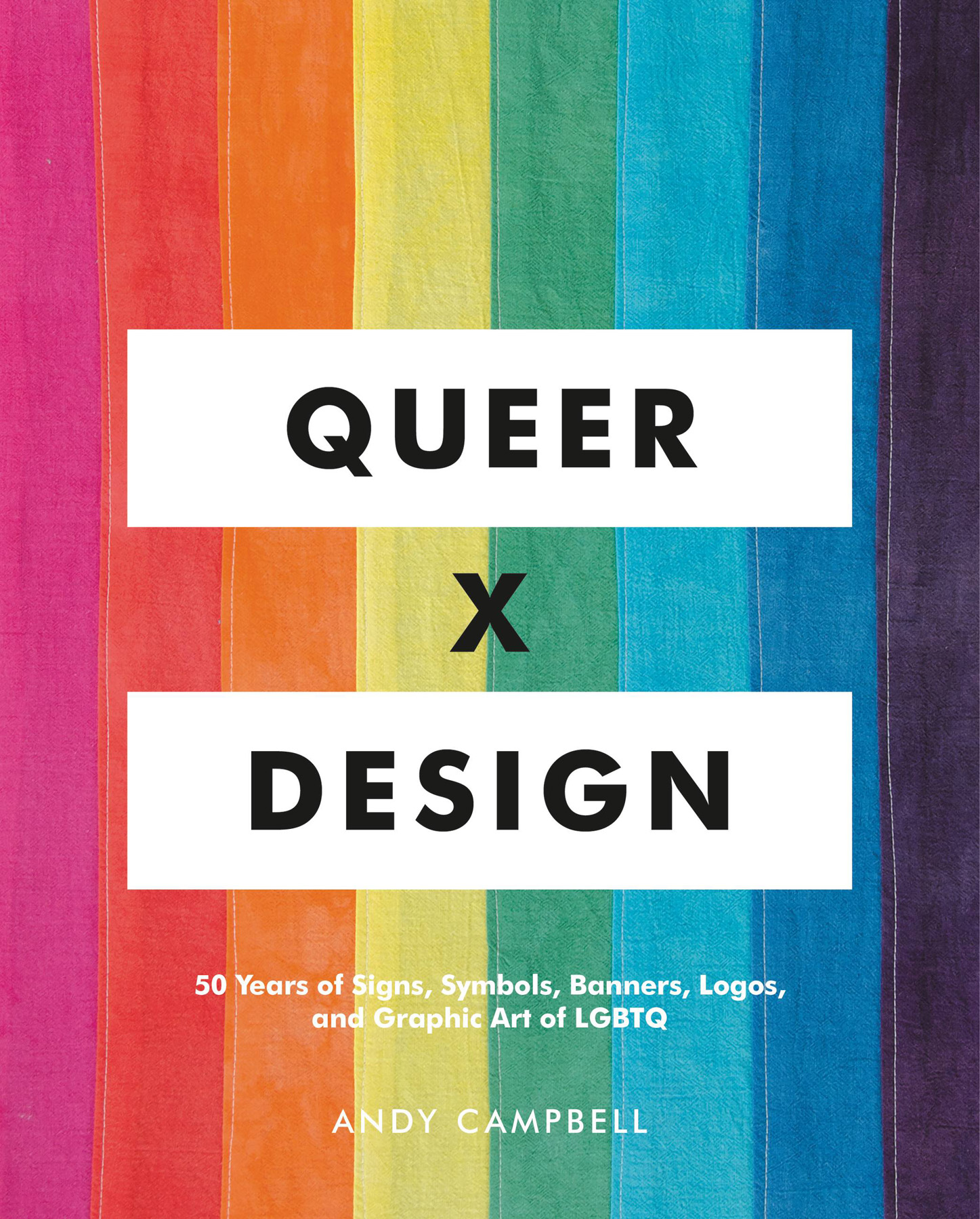

Text copyright 2019 by Andrew Campbell

Compilation copyright 2019 by Andrew Campbell and Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Cover design by Katie Benezra

Cover photograph by Arizona Newsum and Derek Haas 35th Anniversary Rainbow Flag hand dyed and sewn by Gilbert Baker, courtesy of Richard Ferrara The flag in this photograph is signed in the lower right corner and is flag #6 in a series of 35 flags made in 2013 by Gilbert Baker for the 35th anniversary of the creation of the Rainbow Flag.

One of the flags from this series was given to President Barak Obama in June 2016.

Another was added to the permanent collection of the London Design Museum in 2017.

Cover copyright 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

www.hachettebookgroup.com

www.blackdogandleventhal.com

First Edition: May 2019

Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers is an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The third party trademarks used in this book are the property of their respective owners. The owners of these trademarks have not endorsed, authorized, or sponsored this book.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.HachetteSpeakersBureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Print book interior design by Katie Benezra

Back cover art and end sheet art copyright 2019 by Xavier Schipani

LCCN: 2019930099

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-6785-3 (paper over board); 978-0-7624-6791-4 (ebook)

E3-20190320-JV-NF-ORI

Shortly after turning sixteen I was given the keys to my parents rusty, gray Chevy Astrovan. Ready to begin exploring my hometown of Austin, Texas, one of the first stops I made was the local gay bookstore, Lobo. There I bought a thin, rainbow-striped bumper sticker with the intention of immediately adhering it to the back of my new car. In my head such an action was a declarationa public claiming of a piece of my identity I was still coming to terms with. But this potential for increased public visibility forced me to pause and reconsider. What if the sticker inflamed a fellow driver, causing an accident on the road? What if I got nasty looks or terrible catcalls? Was I prepared? This is how I came to be petrified in the midst of my teenage liberationunsure of what I was doing or what the potential consequences might be. This existential crisis likely only lasted half a minute, but I remember time creeping to a halt with the weight of what seemed like a monumental decision. Snapping out of it, I spat on a paper towel and cleaned the grime off the vans bumper. After peeling the long, slick backing off the sticker, I adhered it to the back bumper.

What I didnt know, but I suppose intuitively believed, was that minor acts like putting a sticker on a car aggregate and have the capacity to shift lived worlds. A thin rainbow stripe on the back of my car was a relatively insignificant yet nevertheless public indication that the driver was an LGBTQ person or ally. Things werent as bad as I had feared, for as many times as I was the target of repulsed glares and shoutslikely due to my bad drivingI received twice as many friendly waves and honks from other LGBTQ folks and allies. Their bumpers sported rainbow stickers, too, and pink triangles, HRC logos, and a variety of queer-positive slogans.

In many respects I was quite privileged. I grew up in a liberal household and city, during a decade when lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender people, and queers were newly welcomed into popular culturealbeit, not with the same zeal or nuance in all cases. Pedro Zamora and Ellen DeGeneres were on television; I could rent Paris Is Burning from the gay and lesbian section of my local Blockbuster (and I did, many times); RuPaul had a talk show on VH1; mainstream bookstores carried a small clutch of lesbian and gay magazines (Out, The Advocate, Curve, and XY) and feminist and gay bookstores carried everything else; I found my first boyfriends in online chat rooms and message boards; and I could avail myself of LGBTQ youth services and counseling if I ever needed them. It seemed that each year more and more people in my own life and in national culture came out publicly, expanding my community by degrees. I didnt yet understand the substantial importance of the decades of activism, struggle, and losses that preceded the good life I was able to live as a young, white, middle-class, gay kid in a fairly liberal Southern city in the 1990s.

StillI remember reading about downtown gay bashings on a semi-regular basis; my mother and I watched in horror as the torture and murder of Matthew Shepard garnered national news coverage; and now, years later, I think of the transgender people who were murdered and whose lives and deaths were so stigmatized that their passing did not garner national sympathy or outrage. I never believed, despite the uptick in popular visibility, or the then-current claims to lesbian chic, that my friends or I were safe in this world. With visibility comes vulnerability; every new milestone of acceptance prompts virulent backlash and bigotry.

My biological extended family didnt truly understand this aspect of LGBTQ life until my cousin, Christopher Loudon, was killed in combat operations in Iraq. In the days leading up to his funeral, word arrived that Fred Phelps and his Westboro Baptist Church congregation, long famous for their God hates fags protests, were planning to picket our familys tragedy. On the day we all gathered at a local church in rural Pennsylvania, Phelpss followers showed up, carrying signs that claimed the death of my cousin was evidence of Gods wrath visited upon a nation that too easily accepted LGBTQ people (fags was their term of art) into their fold. Phelps overstated the casereality and sense often escaped him. My aunts and uncles didnt understand, in the depths of their grief, how anyone could say such vile things. It pressed at the boundaries of my imagination, too, but my world had long included an awareness of people like Phelps. I found that in the midst of our collective mourning, I needed to do a fair amount of educatingand my family, a fair amount of listening.

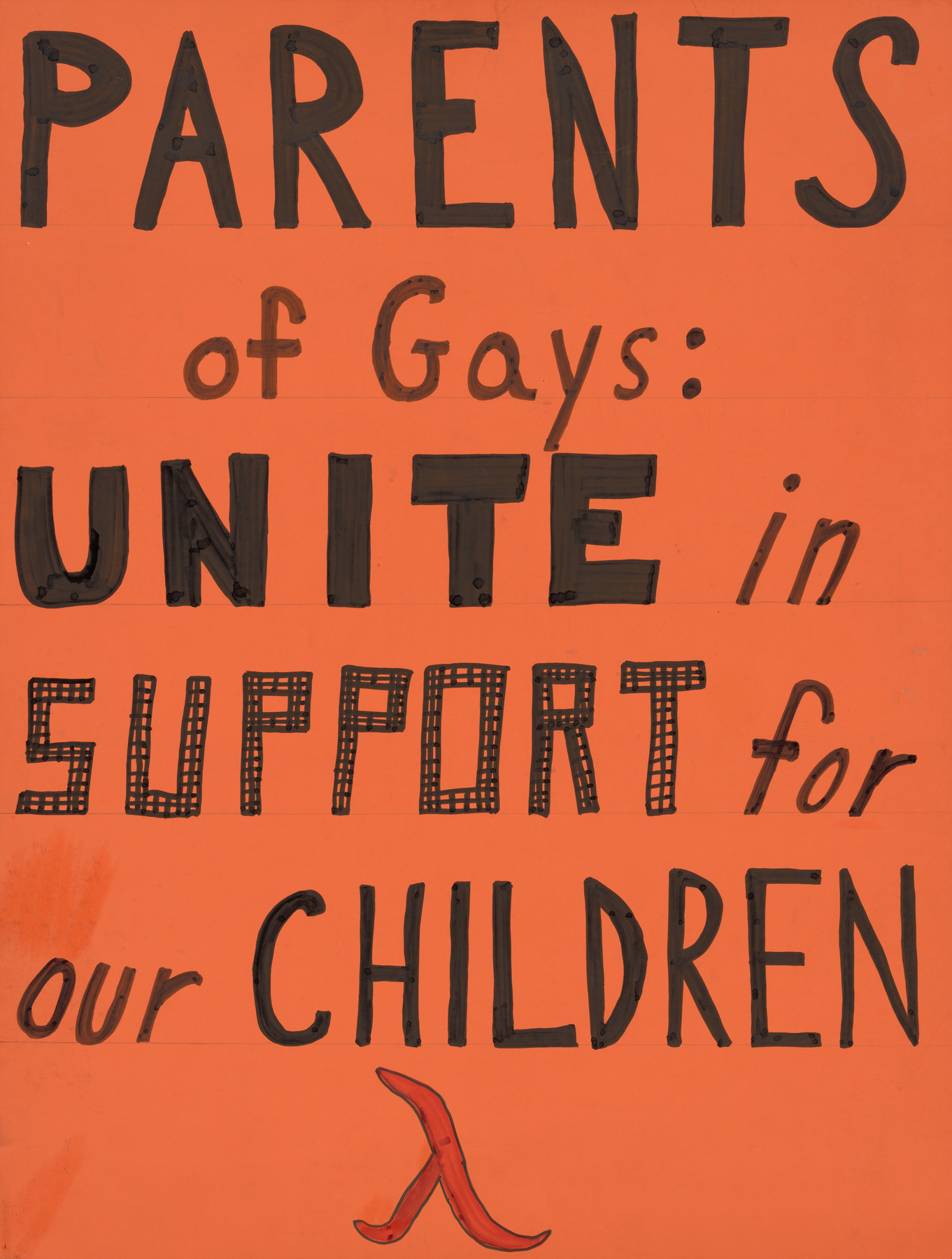

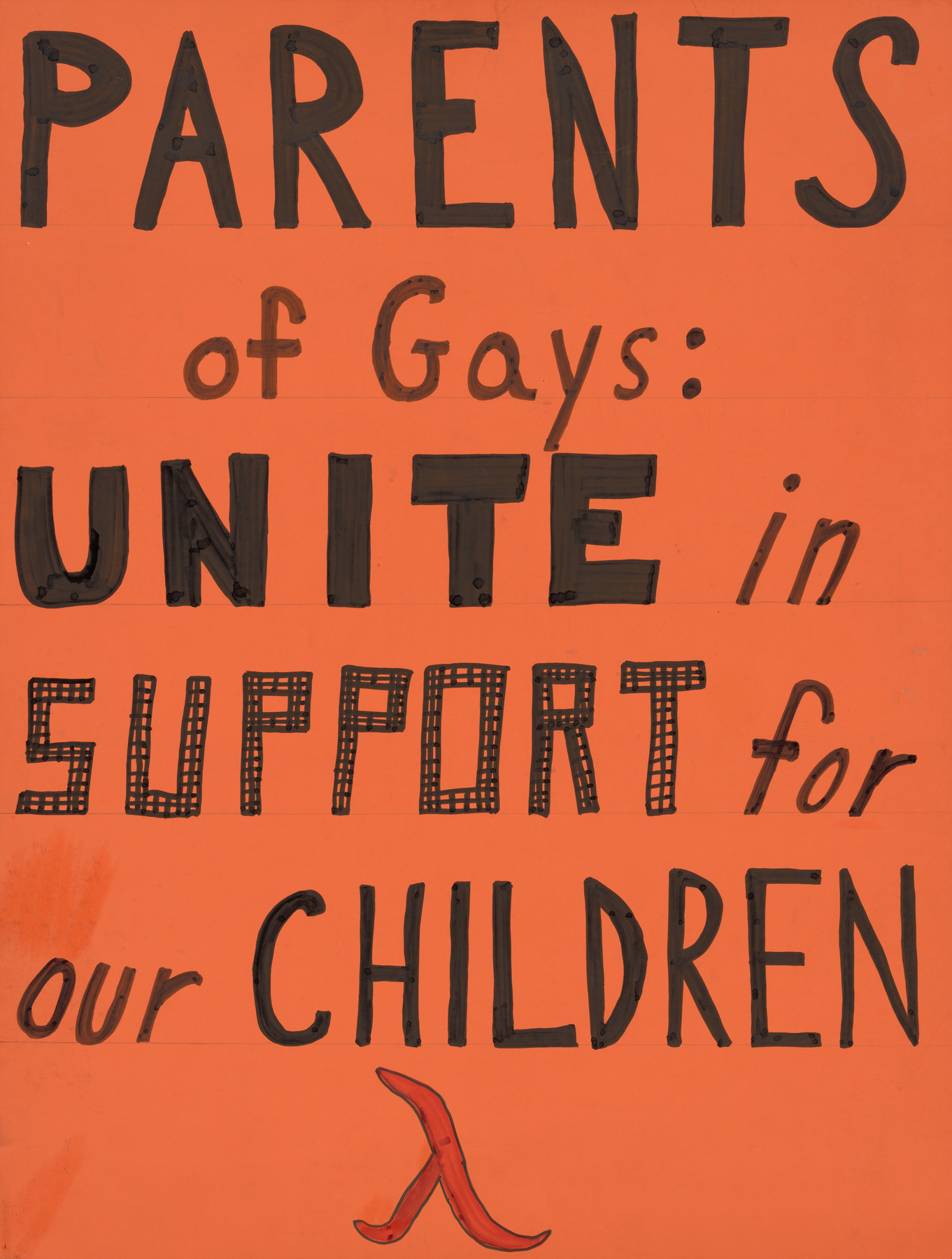

Jeanne Manfords original sign was a precursor for the national organization now known as PFLAG.

I relay these anecdotes to point out the ways that LGBTQ life and politics regularly suffuse both the everyday and the extraordinary, just as the histories of LGBTQ communities are littered with mundane and outrageous acts. And for as much as we understand these histories, or think we understand them, there is still much more to uncover and learn. One of the aspects of LGBTQ histories that has yet to receive sustained attention is the profound importance of design in the social and political livelihoods of LGBTQ people.