All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced by any means whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except brief portions quoted for purpose of review.

Acknowledgments

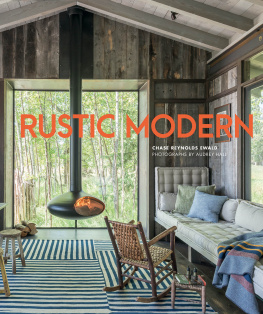

It doesnt take much to put me in a western state of mind. For this lifelong passion I have my parents to thank. They sent me to camp 2,500 miles away at age eleven so that I could wake to the sight of the Tetons every morning, ride western, and learn outdoor skills. Little did they know my Teton Valley Ranch experience would change the course of my life.

I owe a huge debt to Oak Thorne, who gave me my first wrangling job, and to Duane and Sheila Hagen at Hidden Valley Ranch, who hired me sight unseen because my horse was a good hand. Bo Polk and Bob Curtis stepped out on a limb when they backed me in running Breteche Creek Ranch, a nonprofit educational guest ranch in a remote valley with no electricity or phone. All these people taught me about western hospitality, western design, and western can-do; if it werent for them I wouldnt be doing what I do today.

In the making of this book, many people invited Audrey Hall and me to share their campfire. We extend our heartfelt thanks to John and Kathryn Heminway, Hilary Heminway, David and Alexia Leuschen, Tom and Patty Agnew and the Women of the Wild West, George Wanless and Karen Carson, Chris Ellis, Foster and Lynn Freiss, Pete and Melanie Lovelace, Randy and Diane Ross, Doug Tedrow, and Tom and Nancy McCoy. For sharing their thoughts on design and the changing western landscape, we are deeply grateful to Jonathan Foote, Larry Pearson, Rain Turrell, Lori Ryker, Doug Minarik, Tom Norquist, Dave Strike, Kerry Strike, Wally Reber of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Ken Siggins, Jim and Lynda Covert, Rossi Scott, and Scott Boettger of the Wood River Land Trust.

For their gracious hospitality, ongoing support, and enthusiasm, we can never begin to repay Sue Simpson Gallagher, Chuck Neustifter, Dan and Deb Stegelman, Sally Boettger, Kerry Strike, Hannah Ballantyne, Debra Chase, and Todd W. Harris, PhD.

Our meticulous editor, Lisa Anderson, undoubtedly saved us from our mistakes; designer extraordinaire Adrienne Pollard presented our work in the best possible light. Thank you both!

And, finally, for their love, support, and patience in our own western homes, thank you: Charles, Addie, Jessie, Ross, Katherine, and Todd. We love you, and we certainly couldnt have done it without you! CRE and AH

Introduction

"Montana is different from other states because it embodies a single, compelling idea. The idea is: open space, sparsely populated. The idea assumes its own life if we situate ourselves at the heart of this aloneness. When each of us first sets foot in Montana, it would appear we can do what we like with the void. We can fill it, we can exploit we can leave it alone." it, we can restore it,

John Heminway, Yonder

For most people, what's so special about the West is its immensity, its uplifting views, and the exhilarating feeling of freedom engendered by open space, fresh air, and spectacular scenery. But for me the true West lies not so much in its postcard characteristics as in the myriad details that comprise the western experience: the scent of sage on a hot day; the sound of country music wafting through a horse barn; a glimpse of a border collie waiting, ears pricked, in the back of a pickup; the rifle-pinged "Open Range" signs along rural routes; the clink of spurs on a main street sidewalk; a loaded horse trailer parked outside a bar; the cheerful salute of sunflowers along a country road.

On a country-music-fueled road trip in late May, it's redwing blackbirds swooping low along the roadside on a sunny seventy-five-degree day. As soon as the sun dips behind the mountains it will be wintry cold. The snow-cloaked Absarokas massed to the west remind me that a Montana spring is ephemeral, more a suggestion than a season.

I'm skirting the northwest corner of the eighteen-million-acre Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, but this could be anywhere in the rural west. There's Fort Rockvale Restaurant, with its thirty-foot-tall metal frontiersman holding his rifle. Old ranch houses are flanked by mature trees clustered against them, planted long ago as buffers to the winds coming across the flat fields extending all around. A derelict homesteader's cabin is bereft of its windows, as well as half the planks on its roof. It shares a field with a newly built overstated log gatewaya symbolic contrast in today's West.

Although some sights seem eternal, change has come rapidly to this New West, as writer Thea Marx poignantly notes. She describes heading out early for a photo shoot just outside Cody, Wyoming. "As the sun came up, so did reality. This picturesque valley abutting the Absaroka Mountain Range now hosts homes of every shape and size. Plunked into the middle of hay meadows, hovering on the banks of the Shoshone River, and balancing atop the foothills. As a fifth-generation Wyoming ranch girl, my heart aches, for the land is no longer viable production land; it is more valuable as real estate to be subdivided. Ranchers and farmers can no longer afford to work the land. An entire way of life is being eradicated."

Marx's heartfelt sense of loss points to what's needed now in the changing western landscape: an increasingly thoughtful approach to western architecture, design, and living, whether it's realized in sensitively sited new construction, imaginatively repurposed historic structures, old construction updated with environmentally efficient technology, or simply family-friendly western homes that are lovingly maintained and fully utilized. Encouragingly, these types of projects are being seen increasingly throughout the mountain West. Creatively designed, thoughtfully conceived, the new Western homes envisioned here are merely a starting point in preserving the very values that make the mountain West so exhilarating, and so unique.

In the mountain West, man's impacts were minimal for generations. In the second half of the twentieth century, though, they accelerated rapidly, and with lasting consequences.

The earliest inhabitants of the mountain West imposed insignificant impacts on the land. The Native Americans lived in tepees made from natural materials, and, since they moved with the seasons, the land had time to recover between visits. Any lasting impacts look natural in the landscape. A tepee ring, for instance, is simply a number of large rocks arranged in a circle; a corn grinding spot merely a depression in a flat surface of rock; an easily overlooked scattering of obsidian around the base of a rock on a ridgetop indicates that someone sat there looking for game or watching for enemies, and wiled away the time making arrowheads.