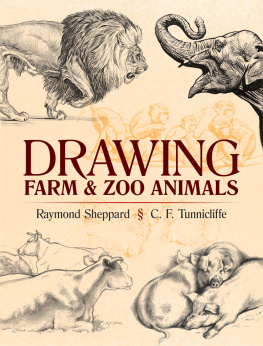

DRAWING

FARM & ZOO ANIMALS

Raymond Sheppard C. F. Tunnicliffe

DOVER PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Mineola, New York

Copyright

Copyright 2018 by Dover Publications, Inc.

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2018, is a republication in one volume of the following works: How to Draw Farm Animals by C. F. Tunnicliffe (The Studio: London and New York, 1952) and Drawing at the Zoo by Raymond Sheppard (The Studio Publications: London and New York, 1949). The text has been newly reset.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Container of (work): Sheppard, Raymond. Drawing at the zoo. | Container of (work): Tunnicliffe, C. F. (Charles Frederick), 19011979 How to draw farm animals.

Title: Drawing farm and zoo animals / Raymond Sheppard, Charles Frederick Tunnicliffe.

Description: Mineola, New York : Dover Publications, 2018. | Series: Dover art instruction | This Dover edition, first published in 2018, is a republication in one volume of the following works: How to Draw Farm Animals by C. F. Tunnicliffe (The Studio: London and New York, 1952) and Drawing at the Zoo by Raymond Sheppard (The Studio Publications: London and New York, 1949).

Identifiers: LCCN 2017046138| ISBN 9780486819150 (paperback) | ISBN 0486819159

Subjects: LCSH: Animals in art. | DrawingTechnique. | BISAC: ART / Techniques / Drawing.

Classification: LCC NC780 .D724 2018 | DDC 743.6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017046138

Manufactured in the United States by LSC Communications

81915901 2018

www.doverpublications.com

CONTENTS

HOW TO DRAW

FARM ANIMALS

Charles F. Tunnicliffe

INTRODUCTION

The Common Boar is, of all other domestic quadrupeds, the most filthy and impure. Its form is clumsy and disgusting and its appetite gluttonous and excessive. Thus wrote Thomas Bewick in his History of Quadrupeds, below his excellent wood-cut of the despised beast. But that was nearly one hundred and fifty years ago and since Bewicks time many changes have occurred in the breeding and in the appearance of our domestic animals. Gone is his Black Horse, his Long Horned or Lancashire breed of cattle (except for a few remnants) and his old Tees-water breed of sheep. To-day, if you were to ask a farmer where you could find a Common Boar he would probably look perplexed and might reply I dunno about Common but I can tell you where there is a Large White or a Wessex Saddleback or a Tamworth boar. And there you have it: the great majority of our modern domestic animals are of definite breeds which are the result of many years of trial and type selection in the endeavour to evolve an animal which will fulfil a particular purpose, with the result that there are fewer and fewer nondescript beasts to be seen on our farms to-day, their place being taken by animals of specialised breeds.

To-day the farms in Britain are being cultivated more intensively than ever before, and the animals of the farm are inseparable from this great activity.

The Horse is still a useful and valued helper in spite of the great increase in mechanical cultivation, while cattle, sheep, and pigs are all very important members of the farming economy, and their importance will probably increase as farming becomes more balanced and passes from this emergency period of strenuous ploughing and crop-raising to one of stock raising.

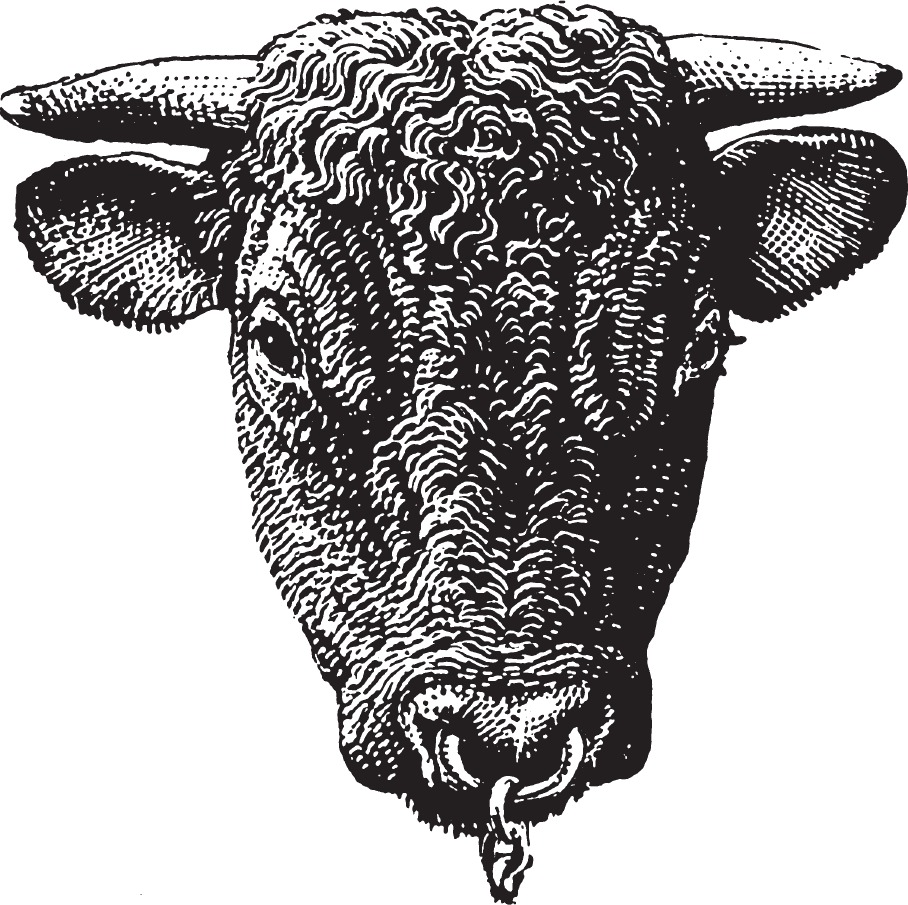

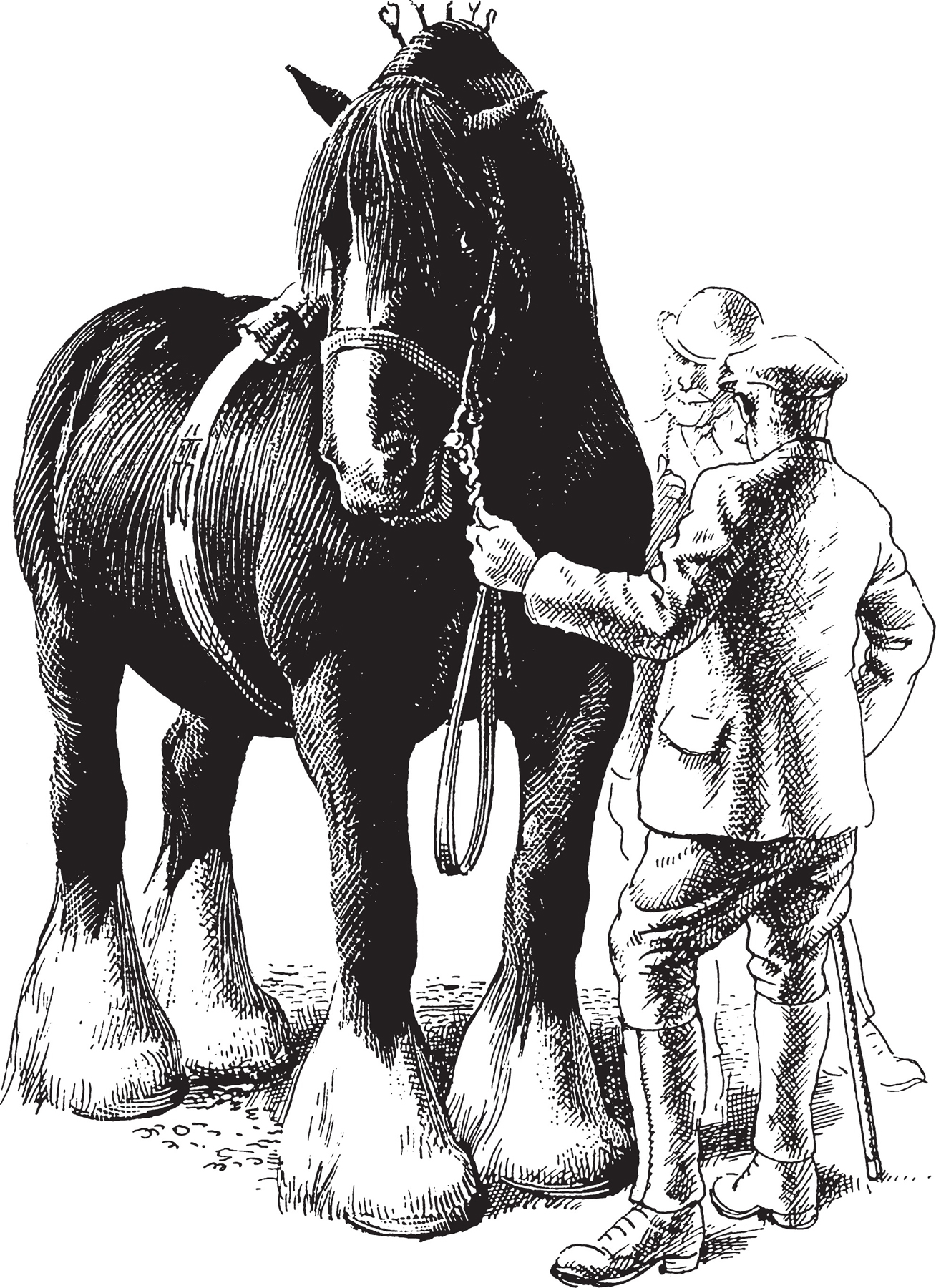

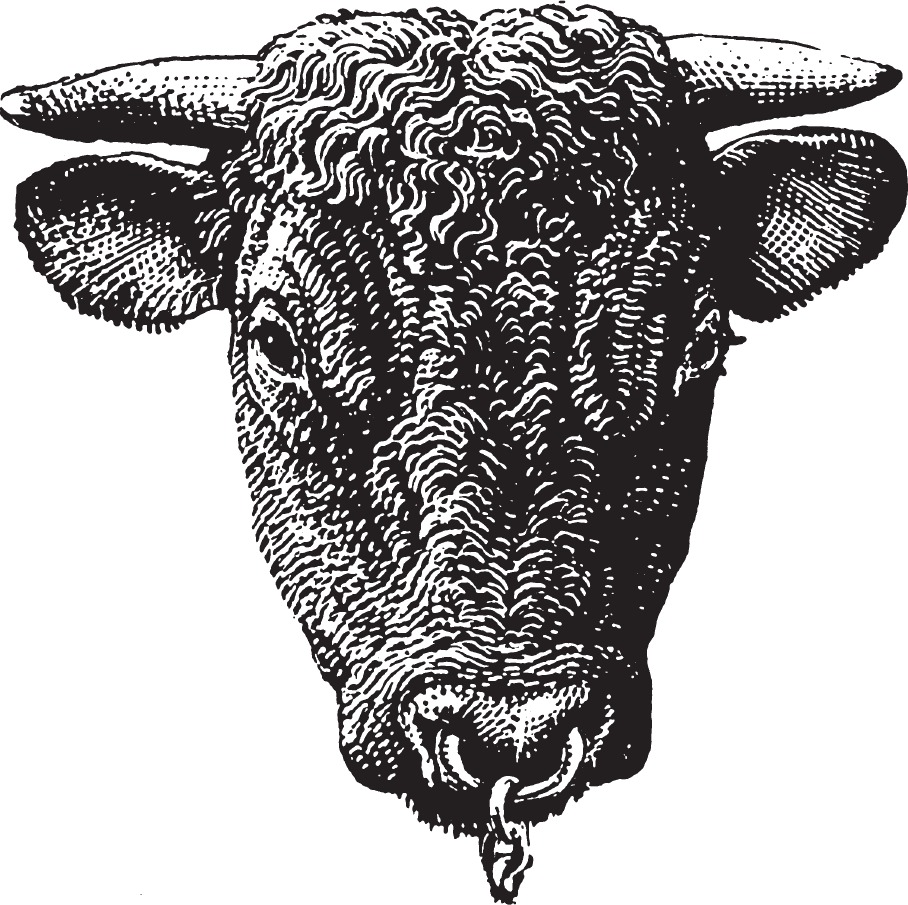

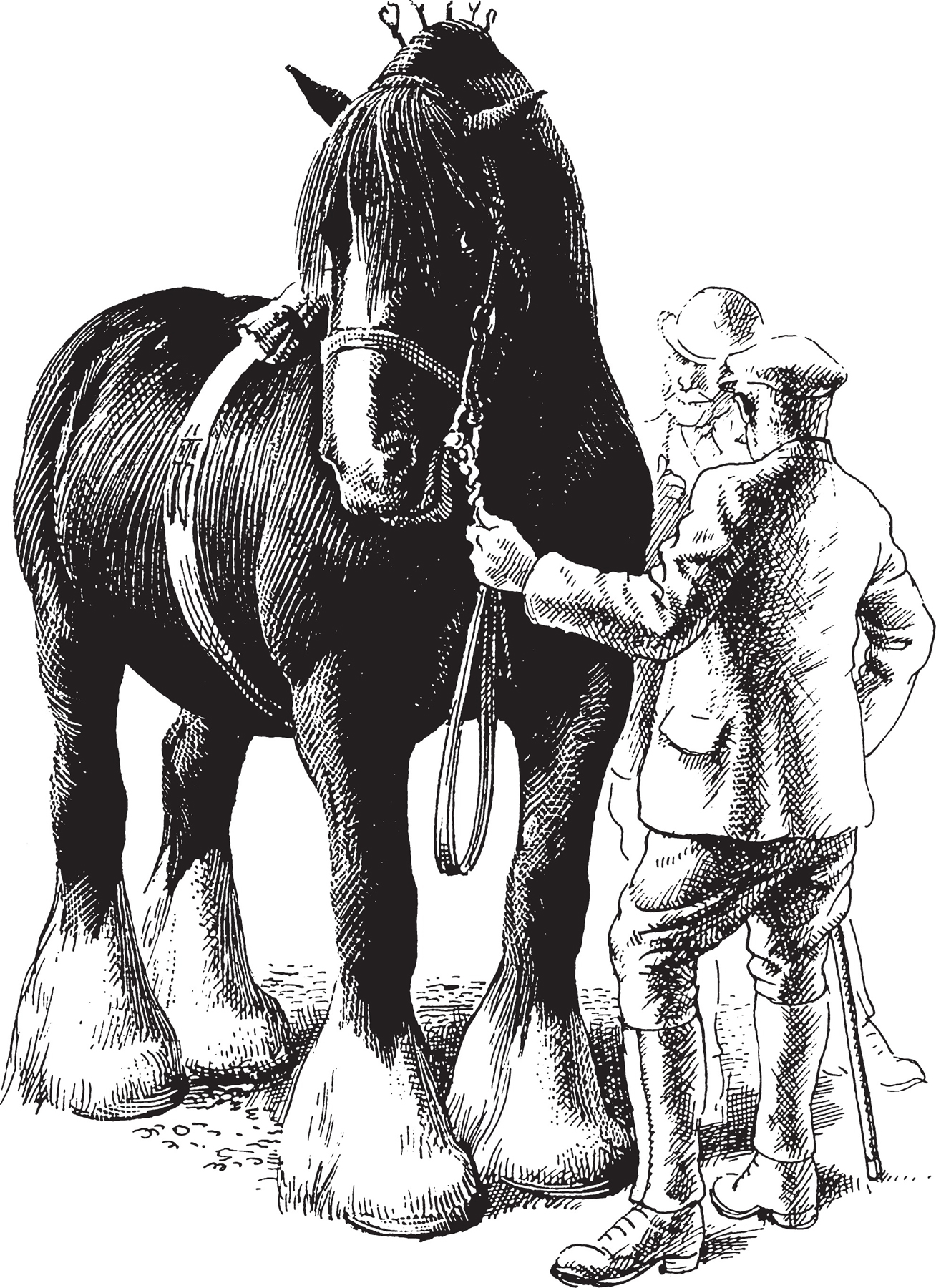

It seems then that the grandeur of the Shire Horse, the impressive shape of the Shorthorn Bull and the delicate beauty of the Jersey Cow will, for many years to come, be part of the farming scene, not only for the profit of the Farmer but for the delight of the Artist also.

As you persevere with your drawing of the animals you will inevitably gain some knowledge of farming ways and procedure, and this will be a good thing, for it will increase your understanding of your models. You will soon realise that, in spite of Thomas Bewicks devastating remarks, the Boar is no longer a despised animal. His form is neither clumsy nor disgusting but has a strong virile beauty of its own, and, given the chance, he is a cleanly beast, both in his habits and his feeding. There is no doubt that, if he could return to us, Bewick would see many and great changes in our domestic animals.

MODEL & MODE

The only practical and sure foundation on which to build your representation of farm animals will be the close study of the living creature.

You may at first find it a little difficult to obtain suitable models but if you make a friend of the farmer and his assistants, and do not make a nuisance of yourself by interrupting farm work, your difficulties will disappear. You may indeed find the farmer a willing helper, for he takes a pride in his animals as a rule and may be a little flattered by your desire to draw them. Also he is an expert judge of an animal, and if you can satisfy him with your drawings of them you may, I think, mildly congratulate yourself.

Afterwards, that which remains to be done is to develop your technique and mode of expression, but in this no farmer can help you, for you will be ploughing a lone furrow, slowly evolving an individual method, stimulated perhaps by the study of the achievements of the masters of animal and figure draughtsmanship of all ages. Remember that animal drawing is almost as old as mankind itself and there is a great and varied field to be explored.

I would suggest that in all cases you begin your studies by drawing animals which are at rest. This will give you an opportunity to make complete studies of form and of more detailed drawings than would be possible from the moving animal.

Later on you can attempt studies of movement. These will of necessity be more generalised statements, but your first drawings of form and details will help enormously in your understanding of movement. Whenever possible handle your animal model. There is no better way of understanding shapes and contours than by having a knowledge of that which is just under the skin. It may be bone, muscle, tendon, or fat, but to know just where these occur is absolutely essential; so run your fingers over shoulders, ribs, hips, and joints, until knowledge gained by touching is linked to that acquired by seeing. In time the correct drawing of the contours of your animals will become instinctive.

When drawing from life, a sketch book with a good stiff binding is desirable. Often you will be standing whilst drawing and in the majority of cases you will be in the open air, so a stiff, board-like backing to the pages is essential. Do not forget to include two elastic bands in your equipment. These will prevent the sketch book pages from blowing about while you work. There will often be a breeze.

For drawing I use a H.B. or a hard carbon pencil and sometimes work over this with inkin my case, brown or black, carried in a fountain pen. But the matter of medium is a very personal one and I suggest you try as many methods as possible from the great variety available until you find the one which suits you best.

And now to Horse!

A SHIRE STALLION

Next page