FIG TREE

an imprint of

PENGUIN BOOKS

FIG TREE

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

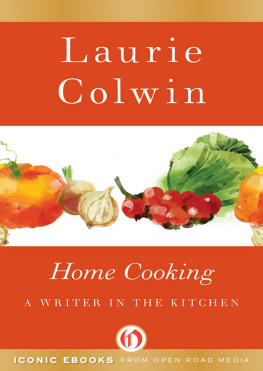

First published in the United States of America by Vintage Books 1988

First published in the United Kingdom with a new foreword by Fig Tree 2012

Copyright Laurie Colwin, 1988

Foreword copyright Juliet Annan, 2012

Illustrations copyright Anna Shapiro, 1988

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-24-196296-1

To my sister, Leslie Friedman

(a great cook),

and to Juris and Rosa

(great eaters)

Home Cooking

As much memoir as cookbook and as much about eating as cooking The New York Times Book Review

Charming and humorous USA Today

Cozy, unpretentious good sense characterizes all her food writing The New York Times

Celebrates a life devoted to food, with chapters on how to cook a meal for several hundred people, how to prepare a gourmet dinner with eggplant in your bathtub, and how to make the best fried chicken in the world

Santa Fe New Mexican

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

ESSAYS

More Home Cooking

FICTION

Passion and Affect

Shine On, Bright and Dangerous Object

Happy All the Time

The Lone Pilgrim

Family Happiness

Another Marvelous Thing

Goodbye Without Leaving

A Big Storm Knocked It Over

Foreword

No one who cooks, cooks alone. Even at her most solitary, a cook in the kitchen is surrounded by generations of cooks past, the advice and menus of cooks present, the wisdom of cookbook writers.

It may seem strange to publish the cookery essays of a writer who died twenty years ago. Although little known outside her native USA, Laurie Colwin wrote five fine and funny novels, three miraculous collections of short stories and two volumes of essays before her sudden death at the age of forty-eight.

But over those years, Laurie Colwins books have never been out of print in the USA. The volumes of essays, Home Cooking and More Home Cooking, are the best selling of all and have just been inducted supreme American honour into the James Beard Foundation Cookbook Hall of Fame. I suspect there are several reasons for these kitchen essays success: the writing itself, which is funny, sharp, warm and welcoming, and provides piles of wisdom about food, cookery and living. The second is that Laurie was ahead of the curve Home Cooking is like Nigella Lawsons How to Eat or Nigel Slaters Kitchen Diaries with fewer recipes and more writing it details how people really live and cook for themselves and others, rather than giving recipes for dinner parties that no one wants to attend. She also wrote about eating proper organic food and farmers markets long before these things existed widely. Beyond that there is the comfort-food aspect of this book its both about comfort food but also it is the book I want to read when I need comfort, when I am feeling low or tired: its about home, and Laurie is full of sympathy and laughter about potential and actual cooking disasters (I love the heading Stuffed Breast of Veal: A Bad Idea). She doesnt talk you out of trying something unwise; she knows you will learn from your mistakes. We learn by doing. If you never stuff a chicken with pate, you will never know that it is an unwise thing to do.

I should declare an interest: Laurie Colwin befriended me when I was in my twenties and living a heavenly, rackety, but I suppose sometimes lonely life in New York in the 1980s. And indeed, I am in this book (see and the dinner given by an English girl in a horrible apartment). She invited me to supper over and over again, and came to my place too. She helped me furnish my tiny studio with some quirky hand-me downs: I still have her wooden spoons, the 1930s salad bowl she gave me, the strange egg whisk she thought was the best. Everything in her own Chelsea apartment was picked with care: she had a passion for flea markets, for brown and white china, for enormous tea cups, for a special kind of straw basket and for antique table linen.

We spent hours together eating and talking about eating. Although she was older than me and one of the bossiest people in the universe, she did not condescend: she was always interested in discussing a recipe, trying something new or finding a brilliant new hole-in-the-wall restaurant where we would go to eat perfect falafel or roast plantains. But best of all was to have her cook for you: her food was simple but sublime, and I can vouch that her recipes for fried chicken and her potato salad are indeed the best in the world.

I learned all sorts of things from her: how to make food look great things that we assume should be served in a bowl often look so much better piled on a platter; and if your guests love something you make, dont be embarrassed to make it again when next they come: they wont, after all, have eaten it in the interim. Some of her rules were weird: she liked to remove the plastic wrapping from all food and put it in greaseproof paper, as she felt the very molecules of disgusting plastic might permeate your food in the fridge. Laurie was not a wildly ambitious cook, she wanted to have a good time when she was cooking for friends, and that is also what makes this book such a treasure for the kitchen and bedside shelf. As in her fiction, she was interested in detail the special species of apple from the farmers market in Union Square, the coffee filter that really worked, the brand of Korean pickle to buy, the final tweak that would make a recipe work.

After Laurie died suddenly in her sleep of an aortic aneurism in 1992, many people wrote about her, but none so well as Anna Quindlen, who wrote ten years after her death: There are certain people so flagrantly alive that their deaths seem an affront to nature. Laurie Colwin was one of those people. The essence of her writing lies not so much in those vivid small details the pecans in the pancakes, the striped wool stockings, the plates painted with cornflowers but in the eternal notion of pushing on through everyday matters into the light of life. It was the essence of her existence, too.