Published in 2015 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc.) in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2015 by Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopdia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopdia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2015 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved.

Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

To see additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, go to rosenpublishing.com.

First Edition

Britannica Educational Publishing

J.E. Luebering: Director, Core Reference Group

Anthony L. Green: Editor, Comptons by Britannica

Rosen Publishing

Hope Lourie Killcoyne: Executive Editor

Raina G. Merchant: Editor

Nelson S: Art Director

Brian Garvey: Designer

Cindy Reiman: Photography Manager, Photo Researcher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Merchant, Raina G.

How eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells differ/Raina G. Merchant and Lesli J. Favor.

pages cm.(The Britannica guide to cell biology)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-6227-5807-4 (eBook)

1. CytologyJuvenile literature. 2. Eukarotic cellsJuvenile literature. 3. ProkaryotesJuvenile literature. I. Favor, Lesli J. II. Title.

QH582.5.M45 2015

571.6dc23

2014026917

Cover (mitochondrium) Mopic/Shutterstock; cover (background), pp. 1, 3, 4, 5 jovan vitanovski/Shutterstsock.com

CONTENTS

E very living thing is made up of structures called cells. The cell is the smallest unit with the basic properties of life. Some tiny organisms, such as bacteria and yeast, consist of only one cell, while large plants and animals have many billions of cells. A human being is made up of more than 37 trillion cells.

Cells exist in a variety of shapes and sizes. For example, they may be cube shaped or disk shaped. Most cells are very small and can be seen only with a microscope. About 10,000 human cells could fit on the head of a pin, though bacteria cells can be even smaller. Some cells are much larger, such as birds eggs or 3-foot (1-meter) long nerve cells.

Regardless of its shape and size, every cell can perform certain functions on its own. A cell can digest nutrients to provide its own energy. It can also produce new cells by making copies of itself, or reproducing. Most cells do this by dividing. In multicellular organisms, each cell must also cooperate and communicate with other cells.

Most multicellular organisms have cells of various kinds. The cells form different structures and perform different functions. Different types of animal cells, for example, form muscles, eyes, or organs. Different plant cells form flowers, fruits, or seeds.

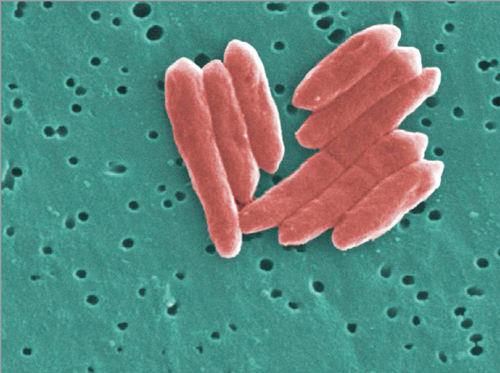

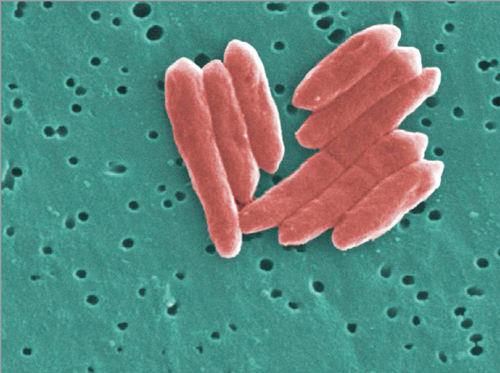

Cells are either eukaryotic or prokaryotic. Bacteria, including the Sebaldella termitidis bacteria, whose cells are shown here, are prokaryotes. Janice Haney Carr/CDC

Cytology is the study of cells and began with the English scientist Robert Hookes microscopic investigations of cork in 1665. Using a microscope of his own design, Hooke observed dead cork cells and called them cells because of their similarity to the small rooms, or cells, where monks live. In the late 1830s, the German botanist Mathias Schleiden and the German biologist Theodor Schwann were among the first to clearly state that cells are the fundamental particles of both plants and animals, thus forming what is known as cell theory. Others confirmed and elaborated on this theory through a series of discoveries and experiments. In the late 1800s, German embryologist and anatomist Oskar Hertwig established cytology as a separate branch of biology.

All cells can be classified as either prokaryotic (cells that lack a nucleus) or eukaryotic (cells with a nucleus). Organisms classified in the domains Bacteria (including blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria) and Archaea are prokaryotes; all other organisms are eukaryotes and are placed in the domain Eukarya.

Prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells are distinguished by several key characteristics. Both cell types contain deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) as their genetic material. Eukaryotes have specialized membrane-bound structures called organelles that do much of the cells work. Prokaryotes lack organelles, though they must accomplish many similar vital tasks. This inability to delegate tasks to their organelles makes prokaryotes less metabolically efficient than eukaryotes. The various similarities and differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells are examined in-depth in the following pages.

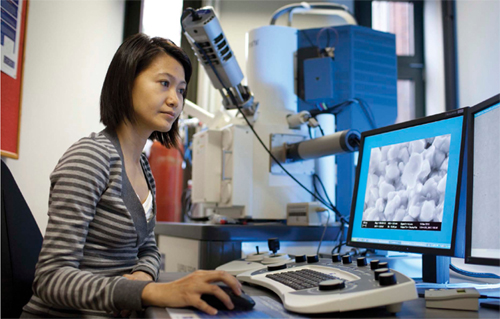

S ince the development of microscopes in the 1600s, scientists have found many ways to study the structure of cells. A typical cell is too tiny to see with the naked eye, much less study. Therefore, scientists use compound microscopes and electron microscopes to learn about cells. With most microscopes, only dead cells or slices of tissue can be studied. The compound microscope, for example, uses light and two lenses to magnify a specimen. Scientists place an extremely thin slice of tissue on the microscopes stage. Through the eyepiece, they study a magnified image of the specimen. Colored dyes used to stain the specimen cause parts of the cell to stand out more vividly than other parts. Electron microscopes reveal cells in even more detail.

The size of cells is measured in microns, or micrometers (m). One micron equals a millionth of a meter (about 25,000 microns equal one inch). Some cells are as tiny as 0.2 microns in diameter. In the human body, most cells are about 10 microns in diameter.

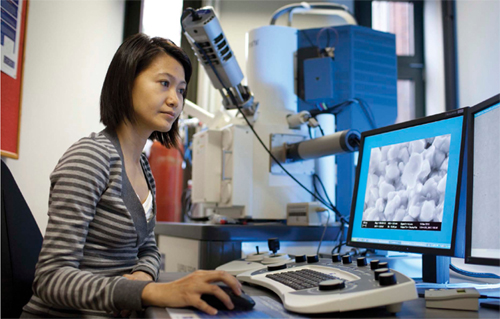

Microscope technology has advanced significantly since microscopes were first invented. Scanning electron microscopes, such as the one shown above, can produce an enlarged image of cells or other tiny samples. Ute Grabowsky/Photothek/Getty Images

APPEARANCE AND SPECIALIZATION

Cells exist in many different shapes, including cube shaped, round, flat, rod shaped, or even spiral shaped. Often, the shape of a cell is related to its function in a body, though even single-celled organisms display a variety of shapes.

Cells have specific functions, or jobs. In single-celled organisms, the cell carries out all tasks relating to the life of that organism. In multicellular organisms, different cells perform different tasks, depending on their instructions from the DNA. Cells work together to form tissues and organs, each with a specifc set of tasks. For instance, brain cells in animals do different work than liver cells. Similarly, plants cells form seeds, roots, stems, and fruits, each of which serves a different function.

As stated earlier, a cells shape relates to its job. For example, skin cells are flat and immobile, which allows them to link tightly together and form a protective covering for the body. Skin cells keep body fluids contained in the body and prevent moisture and pathogens from entering. In contrast, blood cells move throughout the body, and their rounded shape helps them flow easily through blood vessels of all sizes.