Table of Contents

For my parents Rita George (Gihl Lakh Khun) and Andrew George Sr. (Tsaibesa).

To my wife and daughter, Cecilia and McKayla Brazeau-George.

For my brothers and sisters Betty, Brian, Gary, Cindy, Greg and Corinne.

In memory of my grandparents, Thomas George (Gisdewe) and Mary George (Tsaibesa) and my mothers parents, Julie Isaac (Nuyak oohn) and Paddy Isaac (Satson).

Also dedicated to the rest of the George family and the Hereditary Chiefs of the Wetsuweten people.

Andrew George Jr.

For my three families, the Gairns, the Newells, and the Brennans, and for fellow cancer victims everywhere.

Robert Gairns

Foreword

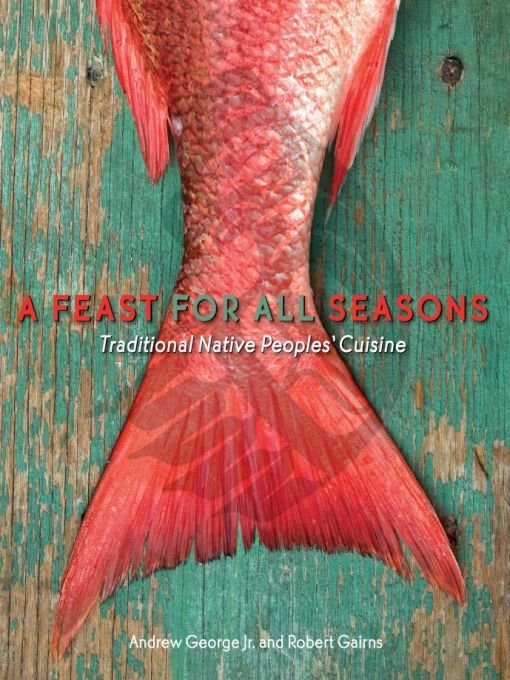

In 1997, when the originaland it was an originalFeast! Canadian Native Cuisine for All Seasons hit the streets, it was pretty exciting for Andrew and me to have our first book published by Doubleday Canada. This came about because a dear friend of mine, who had been published by Doubleday, told them that Andrew and I had a book on the boil that might be of interest to them.

We were offered the opportunity to write Feast by a senior editor. I was sure this would be a losing proposition for us; I have been a writer most of my life. That means I am used to rejection, usually in the form of, We regret to inform you that your manuscript/short story, etc.... Andrew, being an Aboriginal person from the Wetsuweten Nation, was also used to rejection, for different reasons.

But having made the cut, we next had to meet the excruciating pressure of a deadline for Doubledays fall publication season. We had to write hundreds of recipes and a story line that told readers about Andrews personal journey to the Culinary Olympics, the history and culture of his people, Aboriginal foods, particularly of the West Coast, and the significance of foursfour directions, four seasons, four colours, four elementsto Aboriginal peoples.

Quite daunting.

With a typical writers (usually unwarranted) arrogance, I contended that Feast! was a story-book with a bunch of recipes in it. Andrew, in his usual good-natured fashion, held the opposite view. Of course, he was right, but we had fun jousting back and forth, in the same way we did with our favorite hockey teams, his in Vancouver and mine in Toronto.

Now, here we are more than ten years later with another Feast on our handsor should I say in our kitchens and at our tables. We are delighted that Arsenal Pulp Press has chosen to bring this book to life again.

It is our fondest hope that readers of A Feast for All Seasons will embrace not only the delicious recipes from Andrews creative genius but also the stories we tell of a courageous Aboriginal chef and hereditary chief, his people, their culture, and the foods that have nourished and sustained them for generations.

Tawow! Welcome to our world.

Robert Gairns

Introduction to the New Edition

When Robert Gairns and I originally worked together on Feast!: Canadian Native Cuisine for All Seasons in 1997, we wanted to provide an educational tool for the general public on Aboriginal cuisine and an understanding of our customs and culture, which tie our people so closely to the land.

When the book was published, I had moved from Vancouver, BC, back to the traditional territories of my people, the Wetsuweten, or people of the lower river valley (Bulkley Valley, BC), to be with my father who had recently had a stroke.

I held two jobs at the time, one in cooking and the other in natural resources. Because of my participation in the 1996 World Culinary Olympics, all the restaurants and hotels in the area said they couldnt afford me (I was overqualified), so I found work as an Aboriginal liaison between local First Nations and the Ministry of Forests. I was employed with the Office of the Wetsuweten doing land-use planning, assisting with treaty issues, and ensuring that our traditional foods were properly managed and still accessible to our people for use in medicines, food, and for ceremonial purposes. Through the land-use planning process, we tried to protect our traditional berry picking and hunting sites, as well as those that are sacred to us.

One initiative, known as Burning for Berries, was a project in which Aboriginal people worked with logging companies and the government to reintroduce the concept of burning the cut blocks following the log harvest so that the fresh berries, herbs, and mushrooms that grow after a forest fire could flourish. This project also provided jobs for local residents and food that could be either consumed or sold locally.

In the mid-1990s, I also worked as a co-instructor at the Institut de tourisme et dhotellerie du Quebec, a cooking school in Montreal. The sixteen-week course, which I taught twice a year, was developed to leverage the success of the very first Aboriginal team at the Culinary Olympics in 1992, which had won seven gold, two silver, and two bronze medals. The Instituts curriculum was the same as that used during our training for the Culinary Olympics.

While living in the central Interior of BC, I spent a lot of time with my father, Tsabassa (Andrew George, Sr.), learning the cultural ways of our people, and with my mother, Ghil Lahl Khun (Rita George), learning the customs of the Wetsuweten Feast Hall and our protocols. One spring, my wife, Cecilia Brazeau, and I spent six weeks in the traditional territories of the Wetsuweten in my grandfathers territory, known as Biiweni or Lake of Fish (Owen Lake, south of Houston, BC). We walked the same trails and slept in the same camps my grandfathers did prior to European contact. We lived off the land, fishing, trapping, and gathering. Through this process and through the teachings of my parents, I received a hereditary chiefs name, Skitden, meaning the wise man. I am a wing chief of the Casyex House (Grizzly House), and I sit with our head chief, Woos (Roy Morris), of the Grizzly House, one of three houses in the Gitdumden (Bear) Clan.

To introduce real Aboriginal cuisine to the world, I would have to use only all-natural ingredients that come from our traditional territories. I feel that a lot of the foods that are now being promoted as Aboriginal cuisine are only a generic representation of it; the plant foods are modified and what were wild animals are now farmed. One example is smoked salmon, which, rather than being a true smoked wild fish, a genuine Aboriginal food, is often just cold smoked loxfrom farmed fish.

Since the release of the original Feast! cookbook, several chefs in Vancouver and other large cities in Canada have used the book as a reference for Aboriginal content for their own menus. I have also used recipes from this book to design menus for events such as the Tourism Canada Indian Summer festival in Germany and actor Tom Jacksons Huron Carol Christmas show fundraisers for food banks across Canada.

When the announcement came in 2003 that Vancouver would host the world for the 2010 Winter Olympics, I decided to move back to the city so that I could participate as an Aboriginal chef, bringing Aboriginal cuisine to the world stage once again. In 2006 I accepted a position at Kla-how-eya Aboriginal Centre in Surrey, BC, to assist in designing a pre-apprenticeship culinary program primarily serving low-income families of Aboriginal or Mtis decent. The intent of the program was (and remains) to introduce culinary arts to our people as a viable profession. It is currently a sixteen-week program based on the provincial curriculum that also includes life skills, computer training, first aid, FOODSAFE training, and a two-week practicum placement in the industry under a professional chef in the Greater Vancouver area.