All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This is not a manual of cookery, but a book about enjoying food. Few of the recipes in it will contribute much to the repertoire of those who like to produce dinner for 6 in 30 minutes flat. I think food, its quality, its origins, its preparation, is something to be studied and thought about in the same way as any other aspect of human existence.

Anyone who likes to eat, can soon learn to cook well. Such a range of cookery books can now be bought for a few shillings in paperback, from the basic Penguin Cookery Book by Bee Nilson, to the best and most stimulating of them all, French Provincial Cooking by Elizabeth David, that theres no reason for not eating deliciouslyand simplyall the time. So why dont we? After all, in the eighteenth century our food was the envy of Europe. Why isnt it now?

There are many reasons for this, social and historical as well as agricultural and psychological. For a start were so used to eating, why take trouble? There are enough frozen and packaged foods about for even the worst cook to keep her family alive without them noticing how little skill she really has. Intelligent housewives feel theyve a duty to be bored by domesticity. A fair reaction to dusting and bedmaking perhaps, but not, I think, to cooking. The great chef Carme had the right idea when he wrote, From behind my ovens I regard the cooking of India, China, of Germany and Switzerland, I feel the ugly edifice of routine crumbling beneath my hands.

This is not to say that I resist deep frozen and canned and packaged food. I think we should be thankful for being relieved of the famines and inconvenience that the seasons used to bring to so many communities. I have no patience with food puritanism of that kind (though I do wonder why the run of frozen food is not betterwhy so many tasteless sliced beans, when one could have haricots verts?).

Having said this, and being always grateful for the background of an unfailing larder, I feel that delight lies in the seasons and what they bring us. One does not remember the grilled hamburgers and frozen peas, but the strawberries that come in May and June straight from the fields, the asparagus of a special occasion, kippers from Craster in July and August, the first lamb of the year from Wales, in October the fresh walnuts from France where they are eaten with new cloudy wine. This is good food. The sad thing is that, unless we fight, and demand, and complain, and reject, and generally make ourselves thoroughly unpopular, these delights may be unknown to our great-grandchildren. Perhaps even to our grandchildren. It is certainly more convenient with growing populations, to freeze the asparagus and strawberries straight from the ground, to dye and wrap the kippers in plastic, to import hard, red frozen lamb from New Zealand, and to push the walnuts straight into drying kilns. It is easier to put no seasoning to speak of into a sausageit offends nobody, everybody buys it. This is the theory. Were back to the primitive idea of eating to keep alive.

When one thinks of the civilization implied in the development of peaches from the wild fruit, or of apricots, grapes, pears, plums, when one thinks of those millions of gardeners from ancient China right across Asia and the Middle East to Rome, then across the Alps north to France, Holland and England of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, how can we so crassly, so brutishly, reduce the exquisite results of their labour to cans full of syrup and cardboard-wrapped blocks of ice. These gardeners were concerned to grow a better-tasting fruit or vegetable, a larger and more beautiful one too, but mainly a better-tasting one. Would they believe us if we told them that now tomatoes are produced to regular size and regular shape, that only two or three kinds of potato are regularly on sale, that peas taste like mealy bullets? Its odd that we should have clung on to traditions that hardly matterbeefeaters, Swiss guards, monarchies, the paraphenalia of the pastand forgotten the true worth of the past, the long labouring struggle to learn to survive as well and as gracefully as possible.

I do get the impression, though, that people begin to see the problem. The encouragement of fine food is not greed or gourmandise; it can be seen as an aspect of the anti-pollution movement in that it indicates concern for the quality of environment. This is not the limited concern of a few cranks. Small and medium-sized firms, feeling unable to compete with the cheap products of the giants, turn to producing better food. A courageous pig-breeder in Suffolk starts a cooked pork shop in the high charcuterie style. People in many parts of the country run restaurants specializing in locally produced food, salmon from the Tamar, laver and sewin from the Welsh sea, snails from the Mendips, venison from the moors of Inverness. I notice in the grocers shops in our small town, the increasing appearance of bags of strong flour, wholemeal and scofa meal, and the prominence given to eggs direct from the farm.

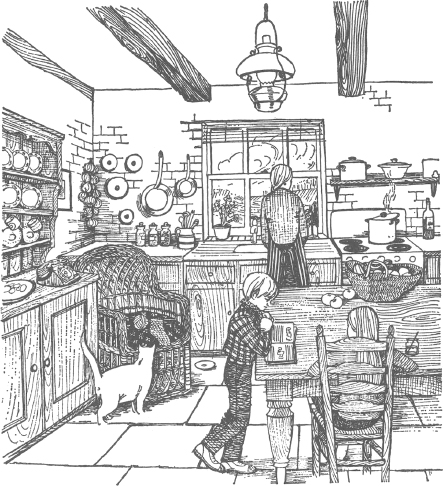

Many families, not just the housewife, now do the cooking between them, and enjoy a protracted sociable meal as an opportunity for talking and discussing with an enthusiasm that was not encouraged at dinner parties thirty years ago. Cooking something delicious is really much more satisfactory than painting pictures or throwing pots. At least for most of us. Food has the tact to disappear, leaving room and opportunity for masterpieces to come. The mistakes dont hang on the walls or stand on the shelves to reproach you for ever. It follows from this that kitchens should be thought of as the centre of the house. They need above all space for talking, playing, bringing up children, sewing, having a meal, reading, sitting and thinking. One may have to walk about a bit, but wheres the harm in that? Everything will not be shipshape, galley-fashion, but its in this kind of place that good food has flourished. Its from this secure retreat that the exploration of mans curious and close relationship with food, beyond the point of nourishment, can start.

I should like to thank Elizabeth David, and John Thompson, until recently editor of the Observer Colour Magazine: they first gave me the opportunity of writing the chapters which follow. Then I should like to thank the many friends and readers who have sent me recipes and information, in particular Mrs Farida Abu-Haidar of Highgate; Mrs Bobby Freeman who ran the Compton House Hotel at Fishguard; Mr Paul Leyton who runs the Miners Arms at Priddy in Somerset; Mrs Mary Norwak of the