ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE

PERSPECTIVES ON CULINARY HISTORY

ARTS AND TRADITIONS OF THE TABLE

PERSPECTIVES ON CULINARY HISTORY

ALBERT SONNENFELD, SERIES EDITOR

For a list of titles in this series see

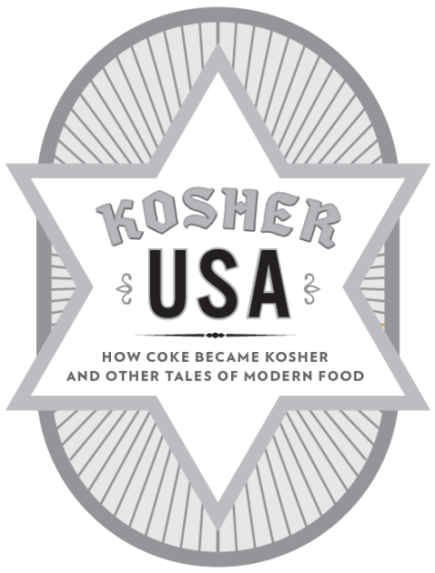

ROGER HOROWITZ

Columbia University Press New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2016 Roger Horowitz

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54093-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Horowitz, Roger, author.

Kosher USA : how Coke became Kosher and other tales of modern food / Roger Horowitz.

pages cm. (Arts and traditions of the table: perspectives in culinary history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Summary: The history of how a set of ancient laws and regulations adapted to modern practices of American food production and foodwaysProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-231-15832-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-231-54093-3 (e-book)

1. JewsDietary laws. 2. Kosher foodUnited States. 3. Jewish cooking. I. Title.

BM710.H675 2016

296.7'30973dc23

2015026798

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design: Jim Tierney

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

TO MY UNCLE STUART SCHWARTZ, WHO MADE ALL OF THIS POSSIBLE.

CONTENTS

UNCLE STUART, my mothers oldest brother, religiously attended the holiday parties at her Manhattan apartment with his wife, Dorison Christmas Day (brisket, not ham, was on the table) and for the Passover Seder. As they aged, it became harder and harder for them to participate, but, because of Stus stubborn perseverance, they came nonetheless. Aunt Doris went through a long struggle with Parkinsons disease that progressively deprived her of control over her bodyand eventually the ability to speak. Stu went to great lengths to bring her, even after he developed incurable bone cancer, and could no longer lift Doris into a taxi as he once had. The last time I saw Stu, at the 2005 Christmas Day party to which my mother invited friends, business associates, and family, the visit was especially difficult. Without the aide who was spending the day with her family, Stu had pushed Doriss wheel chair a mile in a bone-chilling December rain (draping it with clothes and large garbage bags to protect her) from his Upper West Side apartment to my mothers place on 72nd Street.

When they arrived, Stu was only good cheernot a word of complaint. We pulled out my mothers slivovitz (a powerful plum liquor popular among our Romanian ancestors) and drank several shots; he asked after my son and talked about the Spanish lessons he was taking. I told stories and didnt ask after his health or Doris, knowing the answers already and not wanting to dent his upbeat mood. It got late, and Stus younger brother Ernest offered to drive him and Doris home; Stu tried to demur, but, we insisted, the rain had not stopped. As Doris could not stand, and Stu no longer could lift her, I was enlisted to help. So we went downstairs, and I carried Doris from her wheelchair into Ernies SUV and then helped Stuart get in before returning upstairs to collect the raingear he had used earlier. On an impulse, I grabbed the one advance copy I had received of my new book, Putting Meat on the American Table and gave it to Stu in the car. I rode back to his apartment so I could help move Doris inside; we had a chance to talk about the book for a short time before I walked back to my mothers place. I think we both sensed that this might be the last time we would see each other.

A day or two later, he called my mother about the book; she rang a few days later to relate the conversation. He had read it, said he liked it, but wanted to know why I didnt write about kosher meat. After all, it was part of our heritage and should have been part of the story that I was seeking to telland he would like to talk with me about it.

We never had that conversationStu died a few days later. But his question stayed in my mind, even if the opportunity to talk with him again was gone. It was a profound question (befitting a person whom my father once called the smartest man he ever knew) that stirred my mental energiesStu was asking, in essence, was it possible to write about the modern food system and ignore kosher food? Did kosher food fit into the industrial methods that now delivered so much food to our society? Or was it in some way marginal, excluded, unimportant in modern secular society? What did that answer say about the place of Jewish traditions in American culture? His question also pointed to how I might bring something unusual to an answerpersonal experience growing up in a kosher household, and the scholarship to conduct the necessary research. Much as this Christmas evening left a riveting impression on me, it was Stus intellect and insight that put me on to this project for almost a decadenot sentimental obligation; and I think that was what Stu would have wanted.

Shortly afterward, I related these thoughts to my colleague and friend Arwen Mohun, who caught the edge of the issue when she blurted out that Stus question fundamentally was about religion and modernity. How could a set of practices and beliefs rooted in antiquity persist, and in some ways flourish, but at the same time also struggle to survive in a society ineluctably shaped by different religions and belief systems? Her insight only reinforced to me the value of answering Stus question.

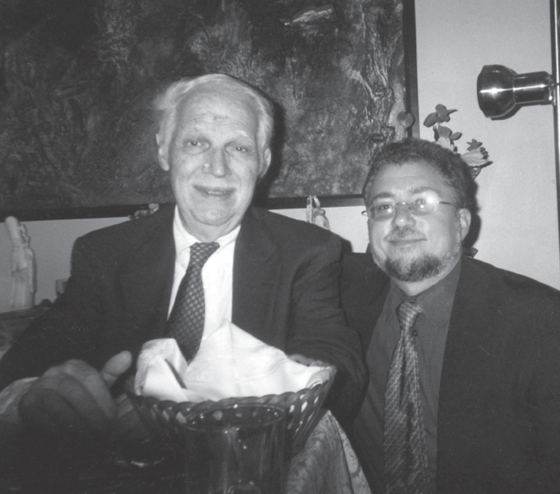

FIGURE 0.1 Stuart Schwartz and the author, Passover 2005. Personal collection of Roger Horowitz.