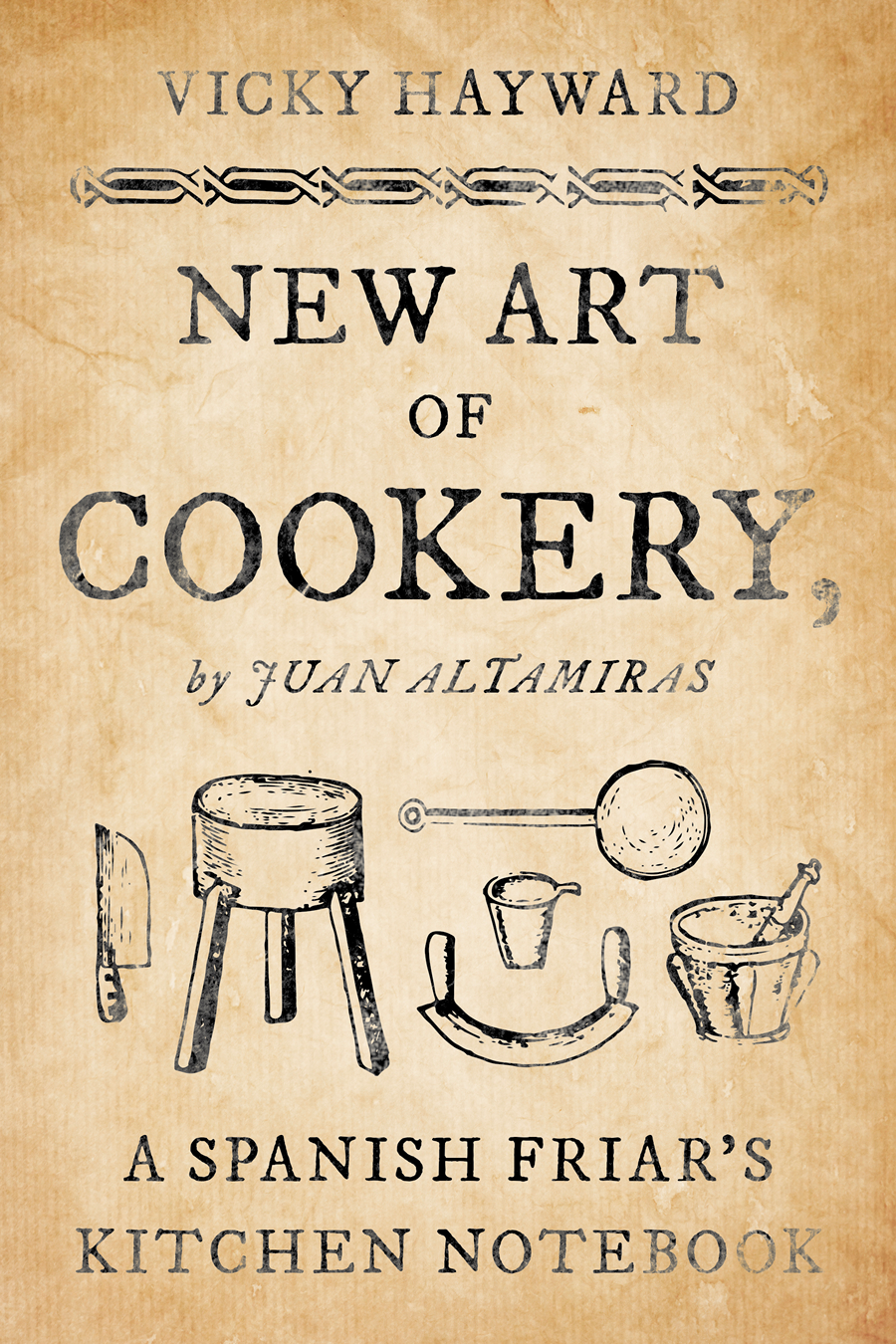

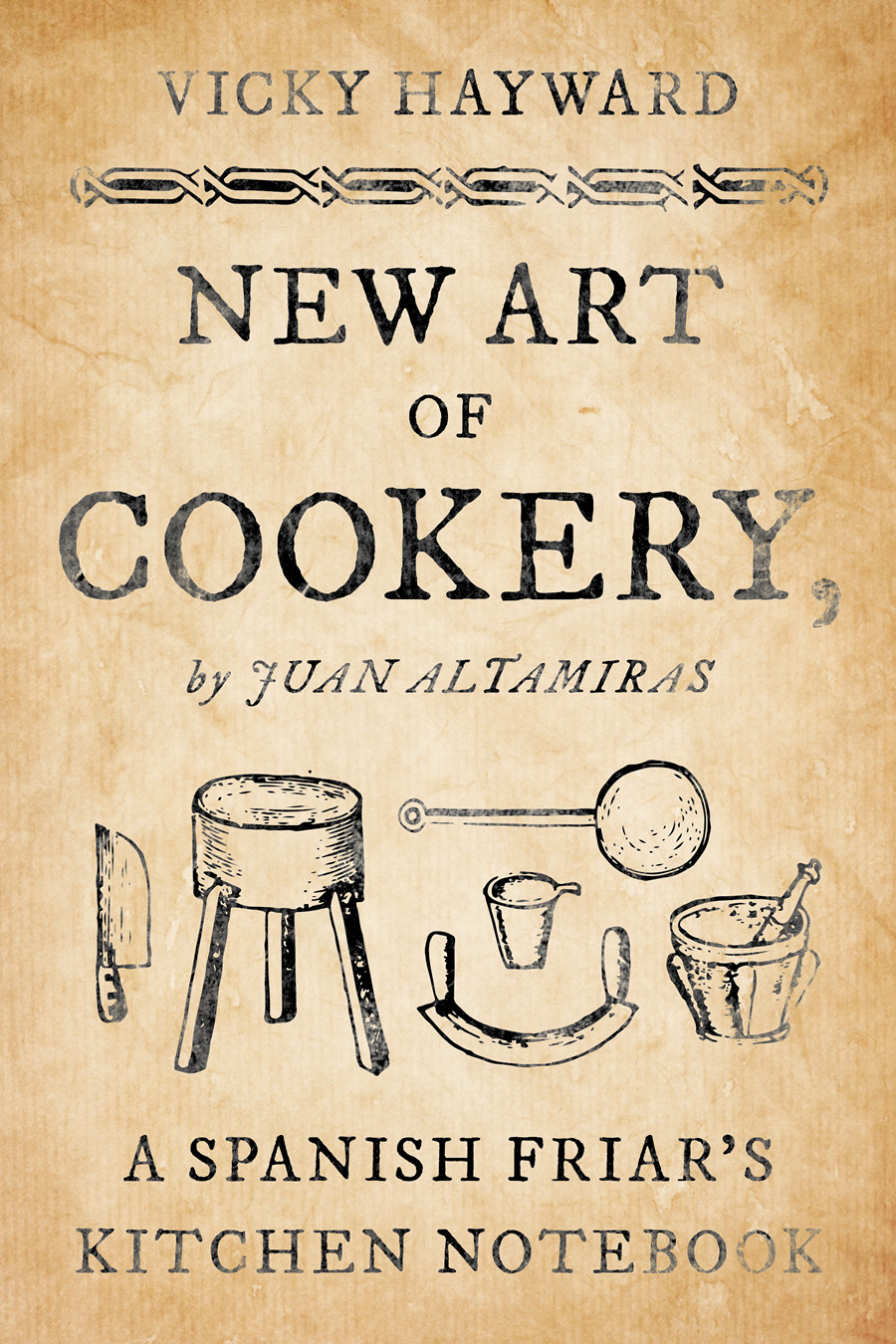

New Art of Cookery

New Art of Cookery

A Spanish Friars Kitchen Notebook by Juan Altamiras

Vicky Hayward

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD

Lanham Boulder New York London

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint material. Blues Castellano, Antonio Gamoneda, c. 1982. One Meatball, Hy Zaret and Lou Singer, 1940 (renewed) by Oliver Music Publishing. All rights for Oliver Music Publishing Company administered by Music Sales Corporation (ASCAP); worldwide rights for Argosy Music Corp. administered by Helene Blue Musique Ltd.

Cover images: Nuevo arte de cocina , 1760, Special Collections Division of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowman.com

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26-34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright 2017 by Vicky Hayward

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Altamiras, Juan, author. | Hayward, Vicky, translator and coauthor.

Title: New art of cookery : a Spanish friars kitchen notebook / by Juan Altamiras; [translated, edited, and with new text by] Vicky Hayward.

Other titles: Nuevo arte de cocina, sacado de la escuela de la experiencia econmica. English

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, [2017] | Translation of: Nuevo arte de cocina, sacado de la escuela de la experiencia econmica. |

Includes bibliographical references and indexes.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016050011 (print) | LCCN 2016059962 (ebook) | ISBN 9781442279414 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781442279421 (Electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Cooking, SpanishEarly works to 1800. | LCGFT: Cookbooks.

Classification: LCC TX713 .A513 2017 (print) | LCC TX713 (ebook) | DDC 641.5946dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016050011

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

I feel

something marvellous

in the beaten silence:

five human beings

who understand life through the same flavour.

Antonio Gamoneda, Taste of Pulses, Blues Castellano (19611966)

Every era of history brings change in the kitchen and every country or village eats to feed its soul, even before its stomach.

Emilia Pardo Bazn,

The Old Spanish Kitchen (1911)

Cocinero antes que fraile.

Spanish proverb

Contents

:

:

:

PREFACE

I n the late summer of 1745 Juan Altamiras, a Franciscan friar from Aragon, published his recipe notebook, New Art of Cookery, Drawn from the School of Economic Experience . I like to imagine him working on it in the kitchen at San Cristbal, the friars summer retreat. Built high on a rocky hillside, its vegetable garden laid out in a valley below, it overlooked the wide-horizoned southern Aragonese plains.

Today San Cristbal stands in ruins. Brambles clamber over fallen stone walls and a spidery fig tree overhangs the path leading to the kitchen garden. Yet the view over the plains has changed little from the one so well known to Altamiras: a patchwork of vineyards, pastures, orchards, and wheat fields, spotted by villages and towns, spreading north towards Zaragoza, the River Ebro and, far beyond, the Pyrenean mountains. Turn south to face the hillside and you can pick out a snow well and hermitage among the boulders rising to sierra peaks; behind those rocky summits lie folded sierras running down to Castile. Travelers to the friary in Altamirass day came north along a dusty road snaking through river gorges, or they traveled west and south across the plains from Cariena and Zaragoza. Don Quixote and Sancho Panza had ridden along the very same flat roads to watch the jousting in Barcelona.

Altamiras, a clever man, may have foreseen the success of his little recipe book. His prologue suggests so. It ran through five editions in his lifetime, then, after his death, it took on a life of its own. The slim book grew in size as editors fattened it out with new recipes, but it kept its title, soon a brand, and remarkably it kept reprinting at a time when French cookery held sway in wealthy Spanish households. Franciscan missionaries also carried copies to Texas, Mexico, Peru, Venezuela, and California where they were traveling north and building missions along the Camino Real. By 1905, a hundred and sixty years after its first publication, New Art had run through twenty editions or more.

A long pause followed. Altamiras was largely forgotten and the original slim book became hard to find. Then somebody produced a facsimile edition in 1981. This little string-bound volume was pressed into my hands by Jaime Rodrguez, winemaker, as I was leaving Remelluri, his family wine bodega in the Rioja Alavesa, at the end of a flying visit I made there in the 1990s.

Read this, he said. Its important.

One quiet Sunday morning a few weeks later I unknotted the string tying the paper covers and began to read.

Altamirass cooking drew me in. The aromas of his dishesbraised mutton, fried salt cod with honey, artichokes with cured ham, garlicky chickpea stew, and iced lemonadehung in the air. His writing, chatty, one-to-one, and witty, yet serious about cooking and designed for hands-on home cooks in humble kitchens, was memorably phrased. The recipes carried a sense of place. Ingredients like borage, artichokes, saffron, and trout sketched out a little known terroir . Some dishes seemed to emerge from a time-tunnel, their flavors and techniques evoking the Jewish and Muslim legacy. Others gave a sampling of tastes new to Spain, even to Europe. Low on spices, high on ingenuity, these dishes felt modern. For the time there was a rare balance between meat, fish, and vegetables, given equal importance. Frugal food for the spirit was balanced by the odd festive dish for the soul.

Back then, in the 1990s, when Spanish cooking was untying itself from its past, Altamiras came to feel like a friend. Young chefs visually dazzling, avant garde haute cuisine was often thrilling, but it was designed for a privileged few. New Art was an elegy instead to earthy everyday eating and it revealed friary food as something very different to monastic cooking. Shaped by exchange with neighbors, it was improvised around food gifts and kitchen-garden produce as well as the rhythms of the religious calendar.

Shortly after the turn of the millennium, Altamirass calamity and misery of our wretched times, as he called them, reappeared. Hunger and overeating, the hambre y hartazgo of Spains Golden Age, returned to our stuffed and starved world and even knocked at neighbors doors as the new century progressed: I watched queues lengthen in Madrids back streets as the hungry waited for food outside convents and churches.

In 2001, I had written to Basque chef Andoni Luis Aduriz, of Mugaritz restaurant, to ask him where he thought the future lay. He replied in a late night e-mail, which I later quoted in an article, I think in general cooking needs a small revolution. We need to spread a sense of values. We need to ask ourselves questions. His words made my mind turn again to Altamiras. He had wanted to do exactly these same things.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.