Contents

Guide

Page List

For my husband and

favorite chef,

Manny,

who knows the way

to my heart

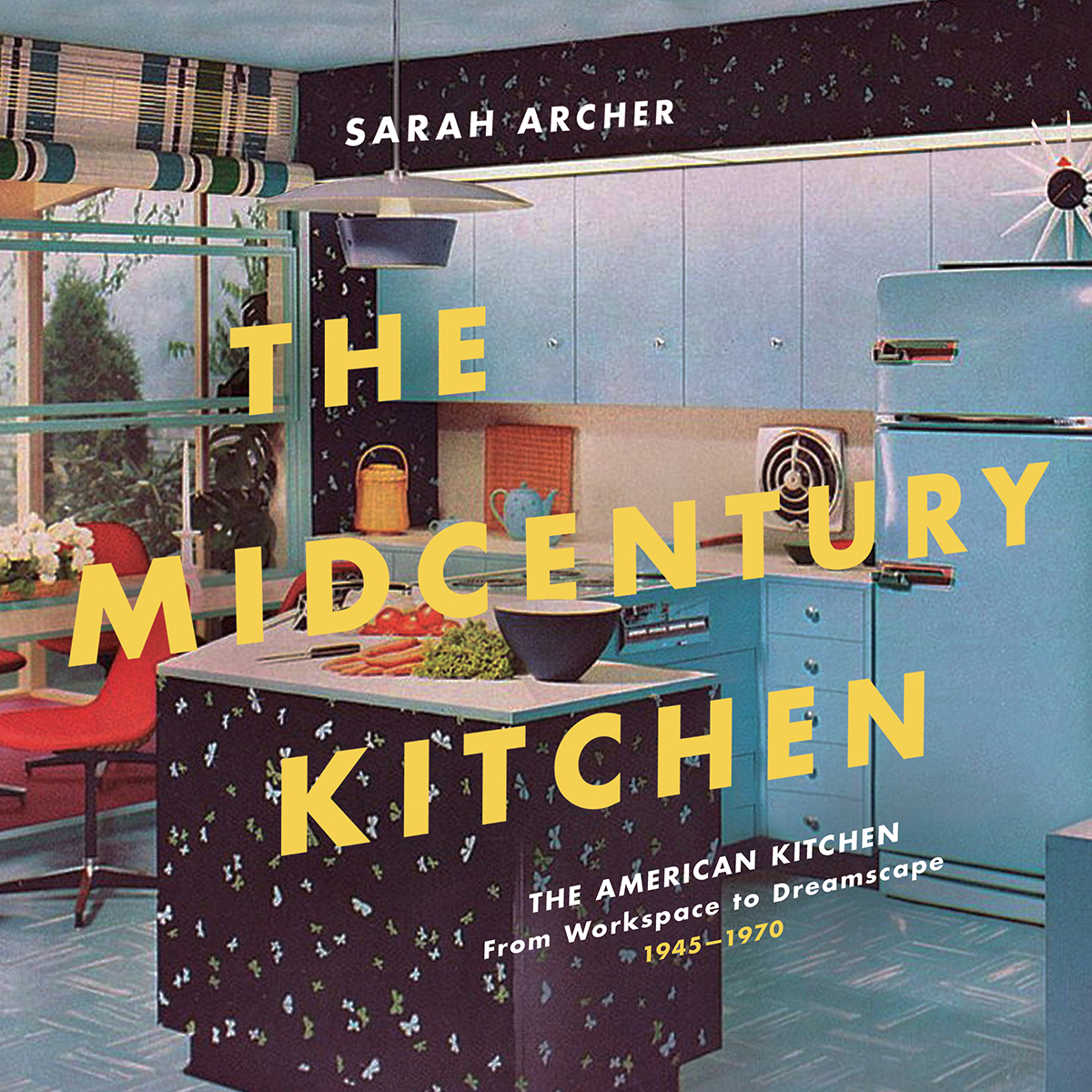

Formica Worlds Fair House Catalog, 1964.

CONTENTS

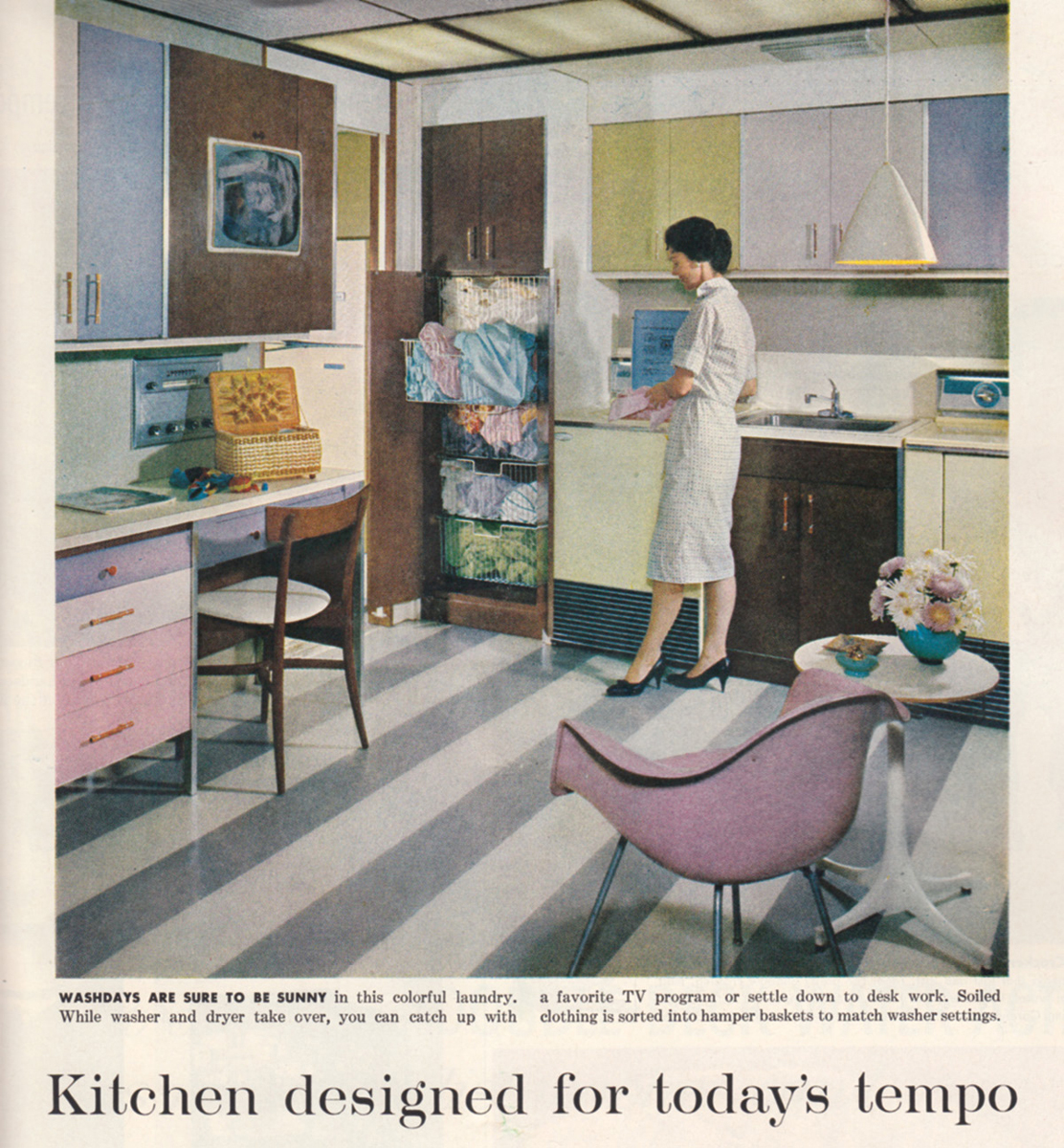

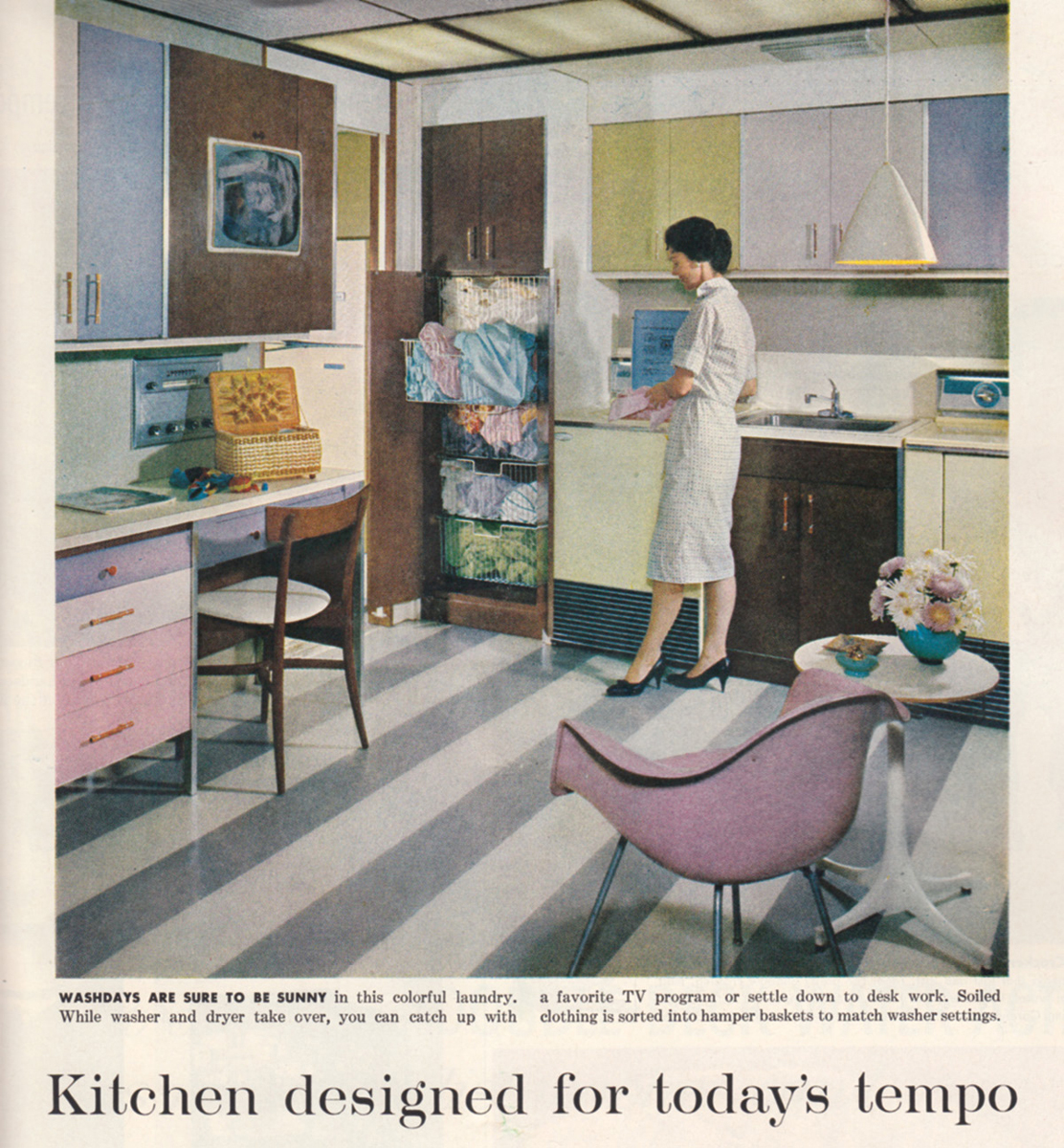

Editorial spread from American Home magazine, April 1959.

Introduction:

Whos in the Kitchen?

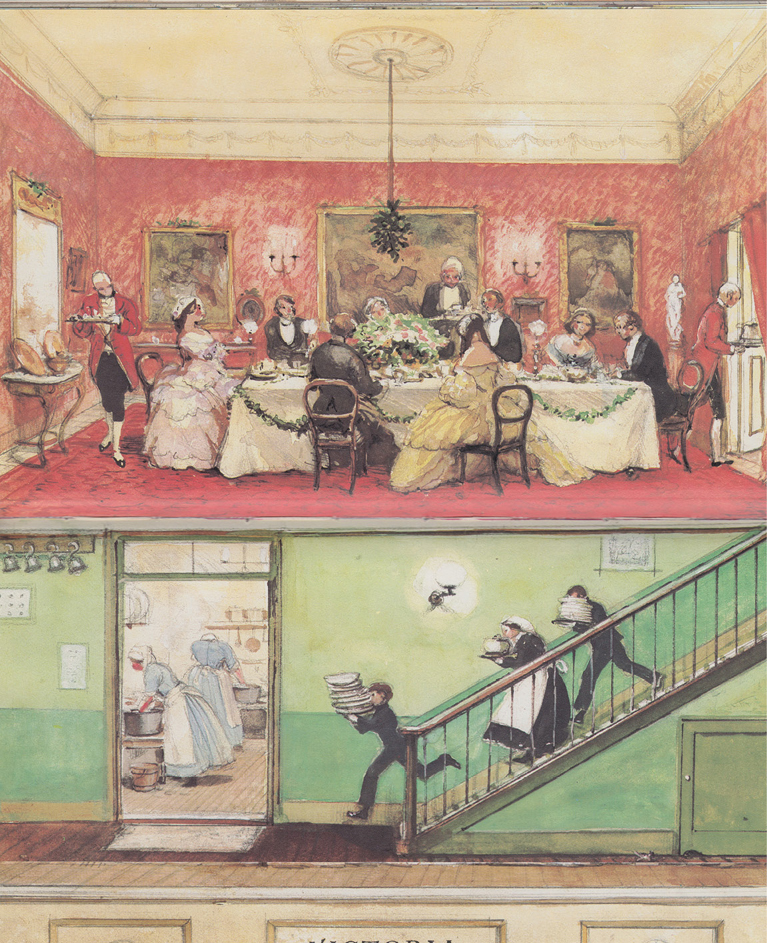

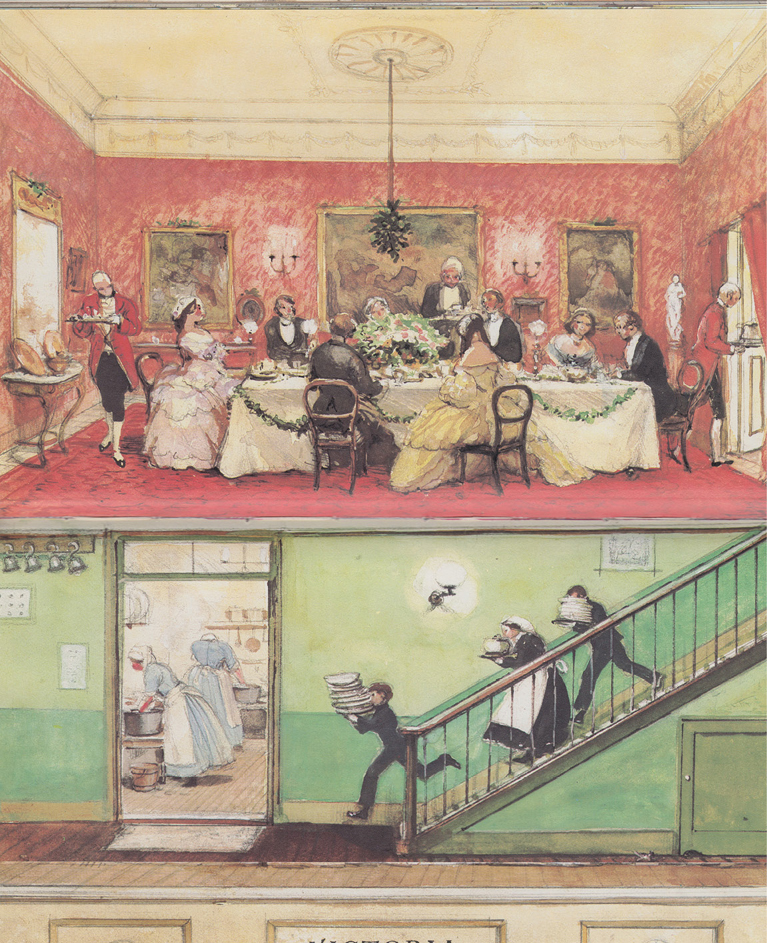

John S. Goodalls classic 1983 childrens book Above and Below Stairs depicts a series of genteel English households from the Middle Ages to the 1980s, shown in cross section, like a dolls house. A half-page flap changes the scene from abovethe world of the well-to-doto below, the world of the household staff who serve them. Its essentially Upstairs, Downstairs in book form, for kids. On page after page, were treated to bright and colorful scenes from the glamorous banquets and parties in the upstairs world. Changes in the style of dress mark the passage of time from one scene to the next. Under the half-page flap, cooks, maids, waiters, butlers, and valets attend to the needs of the lords and ladies upstairs, spanning centuries of technology, from open hearths to cast-iron stoves, year after year, generation after generation.

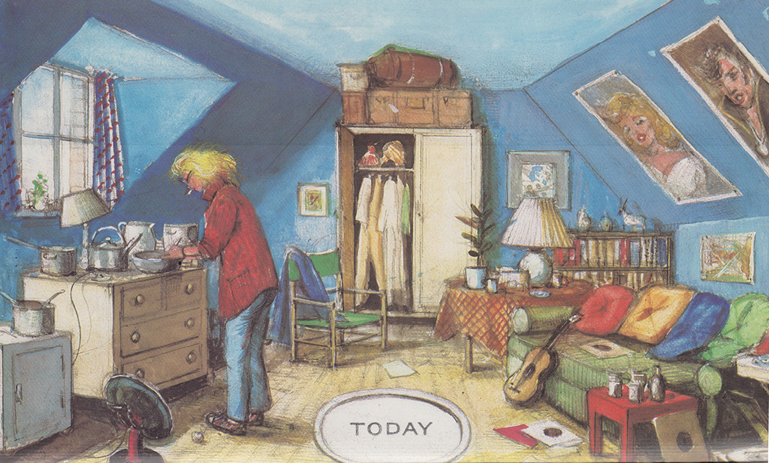

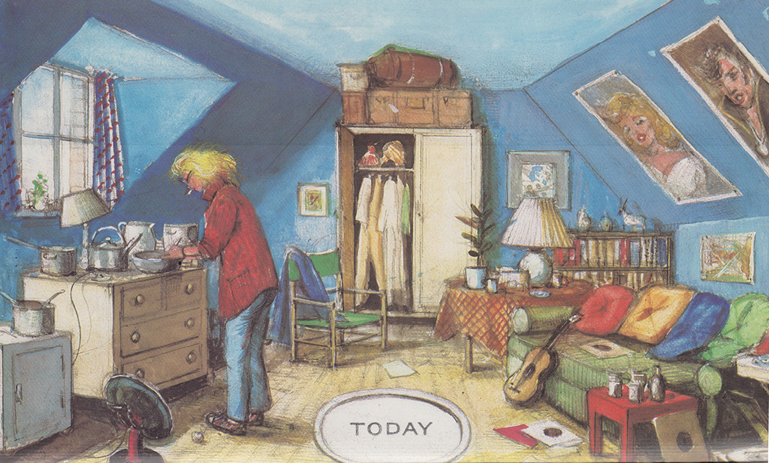

Until the last page. The final scene in the book, which is labeled TODAY, depicts a young man washing dishes alone in a light-filled studio apartment decorated with hanging plants, a hi-fi stereo system, and a futon. Theres no half-flap, no below to make above run. Where did it go? Though it dates from the early 80s, theres something familiar in Goodalls depiction of TODAY. As Americans, we tend to do much of our living in just a few rooms these days, regardless of the size of our living space. The dining room, kitchen, and living room might be subtly distinguished with furniture or half walls, but they nonetheless flow together. Versions of this layout exist across the real-estate continuum: though a modest studio apartment and a luxurious penthouse have very little else in common, they might both have kitchens that look out over the rest of the main living space. And in many middle-class homes, the kitchen is adjacent to an all-purpose family room. In a sense, today we all live both above and below stairs.

Illustration from Above and Below Stairs by John S. Goodall showing a Victorian-era household.

The massive changes in social hierarchies and domestic technology that shook up the class systems in Europe and America are written all over the design of our homes and hearths. According to the 1870 Census, 52 percent of American women surveyed worked in domestic and personal service. This percentage increased in the following decades. But starting around World War I, urban womenboth skilled and unskilledfound that professions like nursing, teaching, factory work, office work, and retail offered better pay and more favorable hours. The economic upheaval of the World Wars and the Great Depression led some families of means to let their household staff go, or reduce their number. The idea that had held for much of history that women either had maids or were maids was ceasing to be true.

Illustration from Above and Below Stairs by John S. Goodall showing a household in the 1980s.

An emerging middle class was the perfect audience for the new domestic appliances that hit the market in the 1920s. Refrigerators that could replace the old-fashioned icebox and sleek electric stoves that replaced the clunky cast-iron stoves of the previous century were often advertised with the kind of glamorous imagery youd expect from the promotion of luxury goods. These were new kinds of machines for a new class of people. One Westinghouse print ad from the period illustrates this point by comparing a new stove to an invisible servant. In the United States, with its mass culture of movies, magazines, newspapers, radio, and department stores, companies could sell both products to furnish consumers daily lives, and ideas about how to live. By the time the American postwar economic boom began in the early 1950s, and more Americans than ever before could consider themselves middle class, the domestic ideal of the modern, servantless home had been rooted in shoppers minds for decades.

One way to trace this transformation is through dramatizations in film and television. In a handful of scenes in the beloved BBC period drama Downton Abbey, a member of the aristocratic Crawley family has occasion to sneak downstairs and poke their head into the kitchen. The household staff, who number at least a dozen, might be drinking a cup of tea and reading the newspaper following their morning rush. Invariably in such moments, members of the staff audibly gasp, their expressions conveying what they cannot say out loud when one of the Crawleys appears downstairs: what on earth are they doing down here? Contrast this with the dynamic of most television shows about middle-class families (and commercials for household products aimed at their audiences) from the 1950s onward: the family practically lives in the kitchen, its workspaces and comforts providing the backdrop for coffee dates, homework, tax prep, science projects, holiday baking, and late-night conversations. The ability to put on the kettle and talk or get down to work somehow makes the kitchen the right place to be for lots of reasons, cooking being just one of them.

Advertisement for the Westinghouse Automatic Electric Range, 1922.

The premise of this book depends on the idea that the kitchen is exactly this sort of discrete living space: cozy, welcoming, and packed with conveniences. In both ordinary kitchens and in those with trophy status, we take this constellation of comforts more or less for granted. But its easy to forget that this is a relatively new idea. The evolving design of the American kitchen, perhaps more than any other room in the house, tells a complex story of work, wealth, status, and changes in the expectations attached to domestic work, gender, and social class. They tell us much about the history of foodafter all, food was, and remains, the star of the kitchenbut even more than that, they illustrate changes in technology and our social relationships. The question of whos in the kitchen determines what kind of room it is, how it works, and what it looks like. Before the industrial revolution, kitchens were not at all considered part of living spaces, and may not even have been physically connected to a primary residence. For the wealthy, the kitchen was just one of several workspaces for household staff. The fruits of the kitchen were to be enjoyed in the dining room, emerging fully formed from a room rarely, if ever, visited by those who owned the house. For the poor, whatever kitchen equipment a family had access to would likely have lined a wall in a single-room dwelling, be it urban or rural.