About the Author

Jay Atkinson , called the bard of New England toughness by Mens Health magazine, is the author of eight books. Caveman Politics was a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Program selection and a finalist for the Discover Great New Writers Award; Ice Time was a Publishers Weekly Notable Book of the Year and a New England Booksellers Association bestseller; and Legends of Winter Hill spent seven weeks on the Boston Globe hardcover best-seller list. He has written for the New York Times , Boston Globe , Newsday , Portland Oregonian , Mens Health , Boston Sunday Herald , and Boston Globe magazine, among other publications. Atkinson teaches writing at Boston University and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize three times. He grew up hearing Hannah Dustons story in his hometown of Methuen, Massachusetts, which was part of Haverhill until 1724.

ALSO BY JAY ATKINSON

Legends of Winter Hill

Memoirs of a Rugby-Playing Man

City in Amber

Ice Time

Paradise Road

Caveman Politics

Tauvernier Street: Stories

An imprint of Rowman & Littlefield

Distributed by NATIONAL BOOK NETWORK

Copyright 2015 by Jay Atkinson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Atkinson, Jay, 1957-

Massacre on the Merrimack : Hannah Dustons captivity and revenge in colonial America / Jay Atkinson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4930-0322-8 (hardcopy) ISBN 978-1-4930-1817-8 (ebook) 1. Duston, Hannah Emerson, 1657Captivity, 1697. 2. Indian captivitiesNew England. 3. Indian captivitiesMerrimack River Valley (N.H. and Mass.) 4. Women murderersMerrimack River Valley (N.H. and Mass.)Biography. 5. Abenaki IndiansWars. 6. United StatesHistoryKing Williams War, 1689-1697. 7. Indians of North AmericaNortheastern StatesHistory17th century. 8. Merrimack River Valley (N.H. and Mass.) History17th century. 9. Haverhill (Mass.)Biography. I. Title. II. Title: Hannah Dustons captivity and revenge in colonial America.

E87.D97 2015

973.2'5092dc23

[B]

2015013265

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

In memory of Maureen Burns Tulley,

because every writer needs a good librarian

I remember in the night season, how the other day I was in the midst of thousands of enemies, & nothing but death before me.

MARY ROWLANDSON, 1682

Prologue

Near City Hall in Haverhill, Massachusetts, on the old two-lane road to Salisbury Beach, is the green, oxidized figure of a stern-looking frontier woman with a hatchet in her right hand, her head angled downward and slightly to the left. She is pointing at something with her left hand, and stands ready to wield the hatchet. As a young boy, I was intrigued by this life-sized statue, which is encircled by a low, wrought iron fence and shaded by giant oak trees. On our way to the beach on a thick, humid summer afternoon, wed cross the Merrimack River on the singing bridge and ascend toward G. A. R. Park, where the statue is located. Sitting in the backseat, Id get my fathers attention and point out the window, asking who was depicted there.

Thats Hannah Duston, my father would say. She killed the Indians.

Prior to 1726 the town of Methuen, where I grew up, was part of Haverhill, and as a teenager I spent a great deal of time camping out, fishing, and roaming the same parcel of woods that contained the Duston homestead and where Hannahs story began. That story persisted in my imagination for many years, and continues to stir debate in local schools, barrooms, and coffee shops. A short time ago, the Duston saga finally worked its way onto my desk and I began spending long afternoons on the third floor of the Haverhill Public Library, in a quiet, seldom-visited room packed to the ceiling with a mostly uncataloged array of rare Hannah Duston materials: local maps and surveys from the early colonial period; yellowed broadsides and historical pamphlets; long-out-of-print local histories; obscure scholarly articles; and other ephemera. A short distance from the library in the storeroom of the Haverhill Historical Society is an assembly of Duston artifacts, including the purported scrap of woven cloth torn from Hannahs loom during the raid; household objects; tools and farming implements; and other items from the late seventeenth century. And, in the company of an energetic local historian, I made several forays into the woods on the northwestern edge of Haverhill, which is still a patchwork of conservation land, dormant farms, ragged brown meadows, and dense stands of fir, oak, and birch trees. It is a stark and thrilling corner of northeastern Massachusetts, a place that looks much as it did three hundred years ago. The Puritans who originally settled this area believed that Satan resided in nature, and that the Indians they had relegated to this dense forest and who sporadically raided their homesteads and farms were emissaries of the devil.

Three years ago, in the predawn hour of March 15, on the 315th anniversary of Hannahs abduction by the Indians, I stood in these woods a mile or so northwest of downtown Haverhill, not far from the banks of Little River. I was in a low-lying, weedy dell close to where the original Duston homestead was located, and where the raiders seized their captives and burned the house to the ground. As a sourceless light came up on the tangled vines and underbrush, shaping out the trees overhanging Little River and revealing the contour of the land as it rose toward what was then called Peckers Hill, I realized this was the place Id been heading all along, in the back of the family station wagon in the 1970s and across my career as a writer. This was the story I had been looking for.

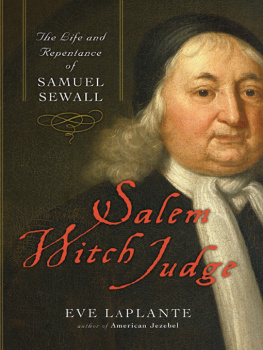

But how to tell it? Once a staple of eighteenth-and nineteenth-century versions of American colonial history, a tale compelling enough to be retold by such literary figures as Cotton Mather, Samuel Sewall, John Greenleaf Whittier, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau, the saga of Hannahs captivity and revenge has been neglected by more contemporary writers and scholars (though it continues to inspire artists). In his introduction to a 1987 illustrated reprint of Mather, Whittier, Hawthorne, and Thoreaus accounts of Hannahs story, the editor Glenn Todd framed in scholarly terms the same questions I had grown up hearing: Is it right for Hannah to kill children because one of her own had been killed? Are Indians less human than the English? What is the meaning of murder perpetrated upon not one, but ten victims who are asleep? Did Hannah kill the children because she thought that if she spared them, they would immediately rouse the Indians at a neighboring camp to pursue her? And is there a more important question: Is this genocide? Is this the ruthless extermination of the Native American race at its root, the killing of Indian children before they can reproduce?... Are Hannahs acts only another instance of the barbarity that underlies all human history, the heart of darkness that cannot be escaped by paddling a canoe back to civilization?

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.