An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

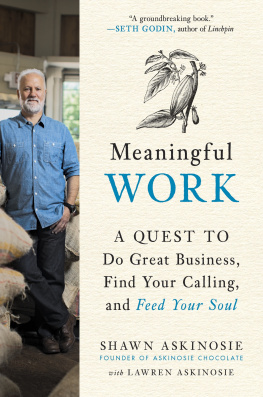

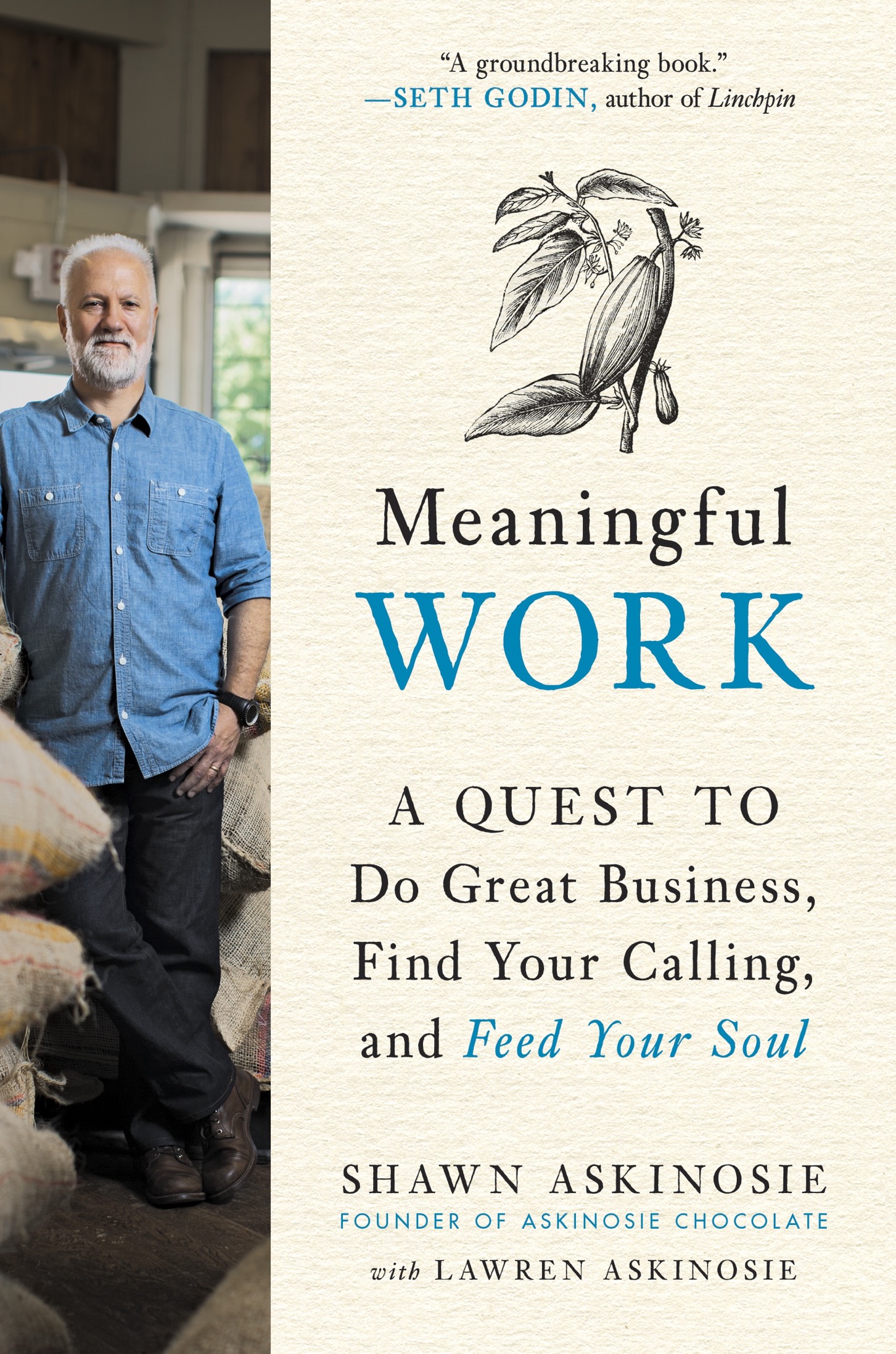

Copyright 2017 by Shawn Askinosie and Lawren Askinosie

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Scripture taken from The Message. Copyright 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 2000, 2001, 2002. Used by permission of NavPress Publishing Group.

TarcherPerigee with tp colophon is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Askinosie, Shawn, author. | Askinosie, Lawren, author.

Title: Meaningful work : a quest to do great business, find your calling, and

feed your soul / Shawn Askinosie, with Lawren Askinosie.

Description: New York, NY : TarcherPerigee, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017022703 | ISBN 9780143130314 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Job satisfaction. | Quality of work life. | Vocational guidance.

Classification: LCC HF5549.5.J63 A795 2017 | DDC 650.1dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017022703

Ebook ISBN: 9781101993774

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Jacket design: Jess Morphew

Jacket photograph: Nate Luke

Jacket images: (cocoa plant) imageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo; (paper texture) Asya Alexandrova / Shutterstock

Version_1

To my wife, Caron

Shawn Askinosie

To my husband, Scott, and my friend Twabwike

Lawren Askinosie

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

What the hell am I doing here, I asked myself again. Im neither Catholic nor a wilderness guyby any stretch of the imagination. I parked and turned around to look in my backseat. I had packed all the requisite stuff: about fifteen books to keep me company, because I had never really been alone before, music, a candle, snacks. Of course, I brought my dog-eared and underlined Tuesdays with Morrie, the Bible, and my favorite Jimmy Carter book, Sources of Strength.

Assumption Abbey is a Trappist monastery that was established in 1950 by its mother house, the New Melleray Abbey in Iowa. A generous donor, inspired by Thomas Mertons Seven Storey Mountain, deeded three thousand acres in Missouri, surrounded by national forest land, to the monks. Still in the drivers seat, as though I was tethered, I reminded myself I was here for a retreat. And also for a special reason.

Arms full of aforementioned stuff, I found my way to the guesthouse. An Irish woman, Bridget, managed it in those days and she greeted me warmly. I think she sensed my uneasiness. There were just nine rooms in the guesthouse, she told me. As she led me down a corridor, she explained that, per my request, she had done her best to make sure that my room was the one in which my father had spent the last night of his life. Standing at the rooms threshold, peering into its sparsely furnished interior, I felt a looming sense of dread coupled with a certainty that this weekend retreat at Assumption Abbey was exactly what I needed to be doing.

More than twenty-five years ago, I wore a suit and tie and stood by my mothers side next to my fathers open casket at his visitation. Id been to funerals before but Id never stood next to a dead body for four hours. As everyone came through the line to offer their condolences and pearls of wisdom about how I needed to be the man of the family, I remember robotically repeating: I just dont know where I would be without my faith. I was fourteen.

During a break in the receiving line, Father Salman approached me. He was an Episcopal priest at our familys church, and my dads good friend. I still remember his enveloping hugs. Shawn, I want to tell you a story about what happened a few days ago at Assumption Abbey when I was with your dad on our mens retreat there. Preoccupied with feigning stoicism, I wasnt interested in listening, but I was a captive audience. It was the last night that we were there and your father came across the hall and knocked on my door around 10:00 p.m. He said, Don, I was in my room praying. I wasnt dreaming. I was just visited by three angels. They told me that I was going to die, that I was going to be okay, and that my family would be protected.

He meant to comfort me, but instead I felt annoyed. Plain and simple, I wanted my dad back and the story of angels wasnt cutting it for me.

Person after person would shake my hand and tell me what a great man my dad was. They were right. My dad was a lawyer who fought for civil and criminal justice. I would often tag along with him to court and watch his trials. Among his many acts of community service, he started legal aid in our town for people who couldnt afford an attorney. He took me with him to the courthouse on Thursday nights and people would be lining a long hallway, waiting on wooden benches, to meet with him. Even though he was out of the Marines Corps by then, he always stayed in good shape, and taught boxing until he got sick. I remember him constantly doing one-handed push-ups. An extremely attentive father, he was the one to come into my room when nightmares struck. I remember the comforting glow of the dial on his Accutron Astronaut watch as he lay in bed with me while I tried to fall asleep.

When I was twelve he was diagnosed with lung cancer. He had not smoked since the military. He went to the Mayo Clinic for surgery and when he came home he and my mom said, They got it all. They didnt.

Our familys faith was supposed to help us cope. I grew up Episcopalian, apparently an appealing denomination for a converted Jew (my dad) and former Southern Baptist (my mom). When my dad became sick we switched to a new church in town, St. Jamess Episcopal, considered the charismatic church, meaning the parishioners spoke in tongues, were filled with the Holy Spirit, and spoke prophetically in services. It kind of freaked me out. Convinced God would heal my dad if my family had the right kind of faith, the church prayer group would frequent our house for impromptu meetings where theyd lay hands on him. The prayer leader, an insurance salesman, would raise his voice at God and Satan during long, stressful sessions. Sometimes theyd stay for hours, doing things I didnt understand but definitely didnt find comforting. He and the others admonished me: Dont talk to your dad about death. It is a sign of weakness and Jesus wont heal him if you have such doubt. So we didnt discuss it. My dad would try to talk to me, but I would say, Dad we cant talk about it or you wont be healed.

There were more surgeries, and though they supposedly got it all each time, he kept getting sicker. His nausea was unrelenting, as was his excruciating pain, for which he needed multiple shots of Demerol throughout the day and night. We didnt have hospice care back then and my mom just couldnt bring herself to stick him with a needle. So the doctor taught me how to give my dad injections. I wanted to help relieve my heros pain more than anything, and this was my chance. By thirteen, I was giving my dad several shots a day, often running out of healthy tissue on his hips. The smell of rubbing alcohol always brings these memories flooding back.