James Beards Theory and Practice of Good Cooking

James Beard

Introduction by Julia Child

Introductory Note

It is wonderful for all of us who treasure James Beard to know that his works are being kept alive for everyone to enjoy. What a pleasure for those of us who knew Jim to read him again, and what a treasure and happy discovery for new generations who will now know him. He reads just as he talked, and to read him is like being with him, with all his warmth, humor, and wisdom.

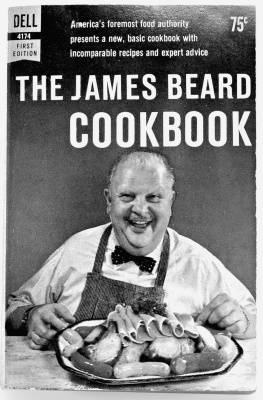

Beard appeared on the American culinary scene in 1940, with his first book, Hors dOeuvre and Canaps, which is still in print more than fifty years later. Born in Portland, Oregon at the beginning of this century, he came from a food-loving background and started his own catering business after moving to New York in 1938. He soon began teaching, lecturing, giving culinary demonstrations, writing articles and more books (eventually twenty in all). Through the years he gradually became not only the leading culinary figure in the country, but The Dean of American Cuisine. He remains with us as a treasured authority, and the James Beard Foundation, housed in his own home on West 12th Street in New York, keeps his image and his love of good food very much alive.

Beard was the quintessential American cook. Well-educated and well-traveled during his eighty-two years, he was familiar with many cuisines but he remained fundamentally American. He was a big man, over six feet tall, with a big belly, and huge hands. An endearing and always lively teacher, he loved people, loved his work, loved gossip, loved to eat, loved a good time.

I always remember him for his generosity toward others in the profession. For instance, when my French colleague, Simone Beck, came to New York for the publication of our first book, my husband and I knew no one at all in the food business, since we had been living abroad for fifteen years. Nobody had ever heard of us, but our book fortunately got a most complimentary review from Craig Claiborne in the New York Times. Although we had never met him before, it was Jim who greeted us warmly and introduced us to the New York food scene and its personalities. He wanted friends to meet friends, and he literally knew everyone who was anyone in the business. He was not only generous in bringing them together, but eager that they know each other. It was he who introduced us to the late Joe Baum of the then-famous Restaurant Associates and The Four Seasons, among other famous restaurants. He presented us to Jacques Ppin, at that time a young chef from France who was just making his way in New York, and to Elizabeth David, Englands doyenne of food writers, as well as to many others.

It was not only that he knew everyone, he was also a living encyclopedia of culinary lore and history, and generous about sharing his knowledge. So often when I needed to know something about grains, for instance, I would call him and if the information was not right in his head, he would call back in a few minutes either with the answer or a source. This capability and memory served him well in his books and articles, as well as in conversation and in public interviews.

James A. Beard was an American treasure, and his books remain the American classics that deserve an honored place on the shelves of everyone who loves food.

Julia Child

April 1, 1999

Contents

Foreword

I miss James Beard. I miss the many classes that we taught together in San Francisco and New York. In San Francisco, we taught for weeks at a time in a temporary kitchen set up by Chuck Williams of Williams-Sonoma in a dining room of the Stanford Court. In New York, we taught at Peter Kumps first temporary cooking school and, of course, in Jims own kitchenthe ceiling, covered in brilliant blue maps; the walls, decorated with copper pots and molds and choice samples of majolica.

My first class in Jims kitchen verged on disaster. He had left me on my own with a group of professionalsand only electric burners (which he preferred) to cook on. I was making bouillabaisse, which requires very high heat to force an amalgamation of the olive oil, the gelatin in the fish stock, and the acid of the tomatoes and white wine. I had had the wit to try the burners to see if they forced a rollicking boil. What I didnt realize was that the burners had heat sensors and would only maintain enough heat to keep the bottom layer of liquid at a boil. The bouillabaisse took forever. In addition, I broke the rouille. The students sneered. By the next day, when I was teaching a class of non-professionals, avid readers of Jims weekly column, I had worked out the worst glitches. The sauce broke again; but I corrected it and the students were pleased. This variation of students was typical of the classes that were a mixed bag of professionalswriters and chefsand would-be professionals. Jim thought everyone could turn a love of food into a profession. He encouraged many to do so.

Even more than the classes I miss sharing good and ample meals with Jim like the ritual first night in San Francisco blood sausage at Le Central, the crack-of-dawn breakfast in his room, and lunches at the old Coach House. However, as I re-read Theory & Practice, I realize that what I miss most are our endless conversations about the history and procedures of cooking.

I admire anew Jims vast knowledge, comprehension, common sense and the conciseness that gives his work its distinctive tone and order. This book was written with Jos Wilson before Jim and I came into each others lives; but many of the subjects formed the leitmotif of our planning for classeswhat we wanted to teach whether organized by technique or ingredient or bothor our agreements and disagreements. The re-issuing of this book can only add to the enormous number of fans and students who made up and still make up his audience. It is a book to treasure and constantly refer to.

The very first time Jim and I met, I was a terrified younger person being interviewed for a job editing a book with which we would both be involved. He was a senior, important person, the general consultant to the book. We had a fightferocious on his part, stubborn on mineabout the way a pt mold should be lined. Fortunately, none of our other disagreements became so heated. This one was resolved the way most of them were with tolerance, affection and neither side changing opinion. I wish I could still chew over with him the way to roastquickly at high heat (my preference) or at lower heat, turning and basting (his method)or whether peppercorns should really be boiled for hours.

Mostly we agreed; but I think it was the passion expressed in our disagreements that brought us so close. We also loved the history of food and could lose ourselves for hours doing research in the books that littered each of our houses.

Teaching was what Jim loved best. He had an extraordinary rapport with students. I never knew him to come away from a class without declaring that it was the best class he ever taught. It is that love of teaching, all the passion, knowledge, and the orderliness of his mind that makes this book so invigorating and useful.

As with The Fireside Cookbook, his first major book,

Next page