Contents

Guide

THE MAN WHO

ATE TOO MUCH

The Life of JAMES BEARD

JOHN BIRDSALL

Copyright 2020 by John Birdsall

All rights reserved

First Edition

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Jacket design: Evan Gaffney

Jacket illustration: Patrick Leger

Book design by Marysarah Quinn

Production manager: Anna Oler

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Birdsall, John, author.

Title: The man who ate too much : the life of James Beard / John Birdsall.

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : W. W. Norton & Company, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020015582 | ISBN 9780393635713 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780393635720 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Beard, James, 19031985. | CooksUnited StatesBiography. | Gay menUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC TX649.B43 B57 2020 | DDC 641.5092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020015582

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., 15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

For Pat Matera and Lou Barker, my long-ago spirit uncles, who taught me how love could bloom behind walls. And for my husband, Perry Lucina, who showed me how to take the walls down.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

In the beginning, there was James Beard. Before Julia, before barbecuing daddies... , before a wine closet in the life of every grape nut and the glorious coming of age of American wines, before the new American cooking, chefs as superstars, and our great irrepressible gourmania... there was James Beard, our Big Daddy.

GAEL GREENE

IF YOU LIVE IN the United States and believe in local food, rely on farmers markets and produce stands to supply flavor and seasonal delight to your cooking; if you take for granted access to milk, butter, and cheese produced in human-scale lots, bakers who employ patience and their hands, and American wines expressive of soil and tradition, you owe a debt to James Beard.

Born in Portland, Oregon, in 1903, Beard came of age when the industrialization of American food was well underway. Starting in about 1940, Beard, in cookbooks and magazine articles and live cooking demonstrations, preached resistance to the dumbing down of food by commercial interests. At a time when the food press was largely a PR wing of manufacturers aligned to profit, Beard argued for taste.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, Americans believed that fine food was synonymous with delicacies imported mostly from France: canned truffles, foie gras, and pt; wines, often cooked en route, that had endured Atlantic crossings without refrigeration. The nascent American gourmet food movement of the 1930s and 1940s was enthralled with imports. In the 1950s and 1960s, however, Beard gained an appreciation for the beauty and vividness of American foodsof smokehouse hams from Kentucky, wines from California, cheeses inoculated with mold and left to ripen in Iowa caves, and fruits and vegetables grown with an appreciation of the soil of the region, by farmers and orchardists who valued flavor more than expediency.

In 1949, he urged city dwellers to grow baby corn on their fire escapes so theyd know the pleasure of freshly picked ears. A decade later, he tried to convince New Yorkers it was worth sourcing eggs from farmers who raised chickens free to roam small-scale poultry yards on the fringes of the metropoliss sprawl.

Starting in the late 1970s, Beard became a mentor to a new generation of chefs yearning to cook in regional idioms, with ingredients culled from the landscapes where they felt themselves rooted. Beard was an inspiration to chefs in the 1980s cooking under the banner of New American. Larry Forgione, Alice Waters, Jeremiah Tower, and Bradley Ogden all looked to Beard as someone who remembered what food tasted like before the supermarkets killed off local butchers and produce stands.

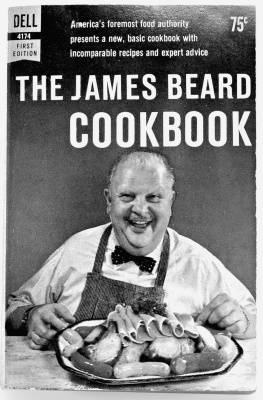

He was also a national character, instantly recognizable to most Americans from the 1950s until his death in 1985. At six-foot-three and hovering around three hundred pounds, James had an enormous physical presence. He was usually genial in public, prone to cornball puns and a folksy delivery that tended to make his audiences lose their anxiety about making a proper souffl or buying a bottle of wine. Beard made it look fun. He embodied Americas culinary identity for most of the second half of the twentieth century. James Beard was American food, its pleasures and excesses, its beauty and simplicity.

He was one of the most famous people in America, and he was terrified that the public would find out who he really was. To the small circle of New Yorks food world, the fact that James Beard was gay was an open secret. To most everyone else in America in the 1950s and 1960sthe people who bought his cookbooks and read his articles and showed up to his cooking classeshis queerness would have been problematic, to say the least. No ecstatic gospel of taste, no wisdom or charisma, would have made the man most Americans had invited into their kitchenseven into their national identities, the man who embodied pleasure in food in a uniquely American wayanything but a pariah.

: : :

IN 2013, I pitched an essay to the quarterly magazine Lucky Peach , for its gender issue, about the closeted male food writers who defined American cooking in the twentieth century. My stimulus was rage.

Lucky Peach was a representation of Americas chef culture, a space where queerness was allowed to flicker only at the margins. A code of straightness ruled the nations restaurant kitchens, an ethos oozing corrosive gender tropes. If you were queer in the kitchen, chances were you didnt dare let your guard slip all the way downan injustice still aching within me, a gay veteran of those battle zones, years after Id left cooking to become a writer. Lucky Peach had built an arena for chefs, yet queer voices didnt rise there. The silence flooded me with grievanceespecially since every chef I knew wanted to win a James Beard Award.

Didnt they realize Beard was gay? Couldnt they see the irony of thirsting after a medal molded with his image, these chefs for whom homophobia was a scar on the face of kitchen culture? And so I pitched my story to Lucky Peach . Chris Ying, an editor, emailed to say hed take it. I wrote furiously, on a short deadline. I called it America, Your Food Is So Gay.