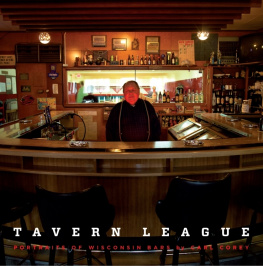

TAVERN LEAGUE

TAVERN LEAGUE

PORTRAITS OF WISCONSIN BARS by CARL COREY

WISCONSIN HISTORICAL SOCIETY PRESS

Published by the Wisconsin Historical Society Press

Publishers since 1855

Photographs 2011 by Carl Corey

Text 2011 by the State Historical Society of Wisconsin

E-book edition 2014

For permission to reuse material from Tavern League (978-0-87020-478-4), please access www.copyright.com or contact the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc. (CCC), 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, 978-750-8400. CCC is a not-for-profit organization that provides licenses and registration for a variety of users.

wisconsinhistory.org

Designed by Percolator

15 14 13 12 11 1 2 3 4 5

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Corey, Carl.

Tavern league: portraits of Wisconsin bars/by Carl Corey.

p. cm.

Includes .

E-ISBN: 978-0-87020-566-8

ISBN 978-0-87020-478-4 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Photography of interiors.

2. Bars (Drinking establishments)WisconsinPictorial works.

3. Taverns (Inns)WisconsinPictorial works. I. Title.

TX950.57.W6C67 2011

647.95775dc22

2011013760

For my mother

CONTENTS

T HIS PROJECT WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN POSSIBLE without the dedication and commitment of the tavern owner who provides the place for community members to gather and enjoy themselves. To you a heartfelt thanks for allowing me to photograph in your establishment and for the welcoming support you have shown me.

Thank you to Jason Smith at the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters, not only for the exposure and support you have provided but also for believing in this project enough to introduce it to the Wisconsin Historical Society Press. To Andy Adams of Flak Photo; Jane Simon, Sheri Castelnuovo, and Stephen Fleischman of the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art; the staff at Blue Sky: Lisa Martel and Todd Tubutis; and also to gallerists/dealers Sherry Leedy, Crista Dix, and Marla Hamburg Kennedy, my deepest appreciation for the venues you have provided, curatorial expertise, and support.

Thank you to Vincent Virga, the extraordinary picture editor and author, and Jim Draeger, historian and author, for your insightful essays; you add so much to this book.

Lastly I would like to thank Kate Thompson, my editor at the Wisconsin Historical Society Press and the champion of this book. Every author should be so lucky.

T HE T AVERN L EAGUE PROJECT portrays a unique and important segment of the Wisconsin community. Throughout history the local tavern or pub has served as a communal gathering place, offering conversation and interaction among neighbors and friends. Bars are also unique micro-communities, offering a sense of belonging to their patrons. Many of these bars are the only public gathering place in the rural communities they serve. These simple taverns offer the individual the valuable opportunity for face-to-face conversation and camaraderie, particularly as people become more physically isolated through the accelerated use of the internets social networking, mobile texting, Facebook, LinkedIn, gaming, and the rapid fire of email.

It is impossible that the Wisconsin tavern can endure this cultural and electronic bombardment without going through transition. Evidence of this is already becoming visible, as there is an increasing number of small tavern closures and the impersonal mega sports bar becomes more prevalent. This series attempts to document Wisconsin taverns as they are today. Heres to them. Cheers!

Carl Corey, 2011

by Vincent Virga

W E HUMANS HAVE A SENSE OF PLACE as strong as a salmon braving up-river or a penguin on the long march. We ignore it at our peril: the resulting alienation results in a death of the heart and ever increasing ecological disasters. Milton may insist: The mind is its own place, but the heart is aligned with Dorothy Gale in the film version of The Wizard of Oz when she declares: Theres no place like home!

As Milton surely knew, home takes many guises in creatures blessed with memory. Every summer when I return to the West of Ireland, my Mayo friends correctly welcome me home, because after two decades of living in their community I feel intuitively how I have come home in body, mind, and spirit. I also call Manhattan home, where I am a native; and home for me is Washington, D.C., where I research and write my books. And Ive yet another home in Dublins Sandymount, where on my annual migrations I regroup in a dear friends house. In each of these places I feel a quiet joy. In each I am secure in my sense of self. In each I feel safe in the world, as I do in several generic environments, such as movie theaters, libraries, museums, and local beaneriesplaces I associate with pleasure and escape from my daily routines.

Like Carl Corey, I am fiercely alert to the spirit of each place, which possesses me via my eyes. Home in wild Mayo is on a peninsula at the base of the sacred Druid mountain Nephin; Lough Conn is on one side of the house and a flowering bog on the other. New York is, well, New York; my landmarks are the neighboring Gramercy Park and the iconic Chrysler building just up Lexington Avenue and on my apartment wall courtesy of Carl. On Capitol Hill Im in a restored convent and the sidewalks are red brick. And Dublin is an elegant Victorian row house beside the Star of the Sea church, where Bloom goes to a funeral near the start of Joyces Ulysses.

Our ubiquitous sense of place did not have its own genre in the visual arts until relatively recently, when landscape painting became a form of human expression. Our emotive spirit of place, however, made its debut as a backdrop or a view out a window in Italian Renaissance paintings. (Think of Mona Lisa.) It was a time when the temporal world first sought equality with the spiritual one, a time when human curiosity defied religious doctrine, a time of immense change in our relationship with the world. It is a time made manifest in the notebook drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, where his studies of place, of the human body and its gestures, and of flowing water become a spiritual experience.

It took several centuries for artists to catch up with him and invent landscape painting. Following his lead, the masters strove to transcend documentation by focusing on form and balance, a technique the Greeks perfected in their pursuit of beauty to instill the breath of life into their art. Somehow it works. We humans respond to the beauty of form with suspension of disbelief and we surrender to the artists vision, the artists particular spirit of place.

Carl Coreys camera lens is a charmed circle. Once we enter its domain, he works his end upon our senses, and with his subjects we all stand spell-stopped. Commonplace words for generic environments, such as tavern or bar, suffer a sea change into something rich and strange before our eyes. The simple words are translated into complex visual metaphors for a type of nest we create for ourselves, nests as sturdy and lovely as those built by swallows, in which our fledgling souls can mingle and find security in the vast, astounding world we all inhabit together.

Carls fascination with the beauty and form of man-made environments, especially the details of indigenous architecture, offer endless delight and encourage us to share his feeling response to what he sees and takes into his charmed circle with us. I look at the splendor of these tavern interiors with a childlike wonder. Some would not be out of place in the Emerald City of Oz or as landmarks on the Yellow Brick Road! And they, like Baums creation, are as American as pizza. They are proud emblems of the American spirit. Like all of us except the American Indians, these glorious structures are transplants to the New World from other, older cultures, and their intricate details and the body language of their inhabitants call up a reverence for the courage and personalities of our pioneer ancestors found in the great novels of Willa Cather.

Next page